Toxic Stress Screening

Guidance for primary care clinicians to screen children and youth for toxic stress

Other Names

Adverse childhood events (ACEs)

Child maltreatment

Psychosocial distress

Social determinants of

health

Traumatic stress

Background

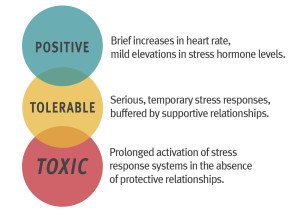

Toxic stress is the strong, unrelieved activation of the body's stress management system at molecular, cellular, and behavioral levels in response to unrelenting adversity without social and emotional support. [Shonkoff: 2012] Moderate, short-lived stress responses can promote emotional growth, but toxic outcomes may result when a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity or trauma without adequate support.

Screening for common adversities (often described as Adverse Childhood Experiences or ACEs) and toxic stress by the medical home helps identify possible risk factors for future medical and mental health conditions, increase communication with families, provide resources to promote resiliency, and mitigate the impact of ACEs, and monitor for stress-related health problems in at-risk patients and family members.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) advises clinicians to consider implementing standardized measures to identify adversities that put children at risk for toxic stress (e.g., maternal depression, parental substance abuse, domestic or community violence, food scarcity, or poor social connectedness). [Garner: 2012] [Shonkoff: 2012] The AAP also advises using structured, trauma-informed assessments to identify and monitor stress-related responses in high-risk families. [Keeshin: 2020] In August 2021, the AAP published an updated policy statement in Pediatrics emphasizing the importance of positive childhood experiences in preventing toxic stress and how safe, stable, and nurturing relationships can prevent toxic stress. [Garner: 2021]

Adverse Childhood Events (ACEs)

Adverse childhood experiences are common and may include a loss of a parent or divorce, trauma or serious illness, mental illness or incarceration of a family member, exposure to domestic violence, abuse, and neglect. Substantial and growing evidence details the negative impact of ACEs on subsequent development, health, and well-being. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study is one of the largest investigations.

The original Ace Study from 1995 - 1997 involved more than 17,000 members of Kaiser Permanente HMO who answered a questionnaire used to identify 10 different ACEs. Almost 2/3 of the study participants reported at least 1 ACE, and more than 1:5 reported ≥3 ACEs. The short- and long-term outcomes of these childhood exposures include a multitude of health and social problems. The ACE score, which reflects the number of ACEs experienced, is strongly associated with adults, in a graded fashion, with an increased risk for:

|

|

Surveillance and Screening for Toxic Stress & Associated Conditions

The AAP encourages ongoing screening and surveillance for ACEs and toxic stress. Options include screening for experiences that can lead to the development of toxic stress, and other screens focus on detecting symptoms that could be indicative of toxic stress, such as behavioral health and traumatic stress symptoms. Some pediatricians present a screener at all well-child checkups, whereas others selectively offer screening (e.g., at the 2-, 9- and 15-month, and the 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year visits). A limited number of tools are available to screen for ACEs that could lead to toxic stress or stress-related symptoms. Most are questionnaires to gather information; a few are formal screens with a cut-off point indicating increased risk.

The following provides examples of accessible screens and questionnaires that are free or low-cost and relatively easy to integrate into primary care use.

Center for Youth Wellness ACE-Questionnaire (CYW ACE-Q Child, Teen, Teen Self Report)

- Available at: Center for Youth Wellness ACEQ & User Guide

- Overview: 17-19 questions screening for stressful or traumatic events experienced before age 18. They are grouped into 3 categories: abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. The Child and Teen versions are parent-reports; the Teen SR is a self-report.

- Time: 2-5 minutes to complete

- Ages: Child (0-12 yo), Teen (13-19 yo)

- Languages: English and Spanish

- Scoring: ACE scores of 0-3 without symptoms should be provided anticipatory guidance; ACE scores of 1-3 with symptoms or ≥4 should be referred for treatment.

- Sensitivity/specificity: N/A (not a validated instrument)

Safe Environment for Every Kid – SEEK Parent Screening Questionnaire, Revised (PSQ-R)

- Available at: SEEK Parent Screening Questionnaire (PSQ-R)

- Overview: 16 yes/no questions. Parent-completed to identify prevalent psychosocial problems that are risk factors for child maltreatment and that generally jeopardize children's health, development, and safety.

- Time: 2-3 minutes to complete

- Ages: 0-5 years. The authors suggest using at the 2-, 9- and 15-month, and the 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year visits.

- Languages: English, Spanish, Italian, Chinese & Portuguese. (Variations in Vietnamese, Swedish, Sorani, Thai, Tigrinya, Turkish, Arabic, Bengali, Dari, Finnish, Kurmanji, Russian and Somali)

- Scoring: Any “yes” response is a positive screen. SEEK provides algorithms to help assess and address key positive screens

- Sensitivity/specificity: N/A

Survey of Wellbeing of Young Children (SWYC)

- Available at: The Survey of Well-Being of Young Children (SWYC)

- Overview: Comprehensive screening instrument incorporating developmental milestones, behavioral/emotional development, and family risk factors. At certain ages, a section for autism-specific screening is also included.

- Time: Varies depending on whether one opts to implement individual screening components or the whole package at each well-check

- Ages: 2 months-5 years

- Languages: English, Spanish, Burmese, Nepali, Portuguese, Haitian-Creole, Vietnamese, Somali and Arabic

- Scoring: The Survey of Well-Being of Young Children Manual (Tufts Medical Center) has scoring details for each screen (cut-offs vary by age).

- Sensitivity/specificity: The SWYC forms and components were compiled from validated screens and compared well to different gold-standard screens; validation studies are ongoing.

Pediatric Traumatic Stress Screening Tool

- Available at: Child Traumatic Stress Care Process Model

- Overview: Provides an easy way for primary care clinics to either use universal or targeted screening for higher-risk individuals. The screens include 15 questions.

- Time: 5 minutes to complete

- Ages: 6-10 years, 11-18 years

- Languages: English

- Scoring: 0-10 mild – protective approach indicated, 11-20 moderate - resilient approach indicated, >=21 severe – restorative approach indicated. Respond to any positive suicide screening questions. See Child Traumatic Stress Care Process Model for more information on response to screening.

- Sensitivity/specificity: The screens are based on the UCLA PTSD Brief Reaction Index, a validated instrument with sensitivity and specificity of 100%/86% using a cut-off score of 21 when tested in an outpatient pediatric clinic serving potentially traumatized youth. [Rolon-Arroyo: 2020]

WE CARE Survey

- Available at: WE CARE Survey

- Overview: 6- to 12-questionnaire about social determinants of health screening and a referral intervention tool

- Time: 2 min to complete.

- Ages: Any pediatric visit

- Scoring: Any “yes” responses are followed up with the option to discuss with the care provider; an additional “yes" requires guidance with community resources.

- Sensitivity/specificity: N/A. The original study explained that the content was validated by expert review and showed high test-retest reliability.

What to Do with a Positive Response

A positive response on a screen for adverse childhood events and toxic stress can be difficult to manage in a short clinic visit. Before using a new tool in clinic, develop a plan for responding to positive screens, whether it is through providing empathy, focusing on family strengths, referring to a social worker, or Help Me Grow National Center. Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) and Poverty & Child Health: Practice Tips (AAP) provide guidance to bolster clinicians' efficacy at responding to positive screens and promote “the 7Cs of resilience (competence, confidence, connectedness, character, contribution, coping, and control), optimism, Reach Out and Read, emotional coaching, and numerous positive parenting programs (e.g., Triple P, Incredible Years, Home visiting, and Nurturing Parenting).” [Garner: 2012]

The AAP offers several courses and interactive learning experiences; every 1-2 years, the AAP offers a 3-day, in-person course, Trauma-Informed Pediatric Provider Course (AAP)), which focuses on the day-to-day issues on addressing ACEs and trauma in primary care.

Also, the AAP, through PATTeR, a Category II Center of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, offers 2 ECHO [case-based webinar]-based learning experiences focused on addressing ACEs, toxic stress, and trauma from a developmental and attachment-based framework. See Pediatric Approach to Trauma, Treatment and Resilience (PATTeR).

The medical home team should provide ongoing identification and evaluation of primary prevention programs, community resources, and interventions that fit their patient population.

Coding

CPT Coding

Use CPT code 99420 when assessing a child’s risk for adverse

childhood events.

ICD-10 Coding

The following codes are appropriate for the common presentations of

toxic stress and the experiences leading to it. Consult ICD10Data.com for other presentations.

F43.0, Acute stress reaction

F43.1x, Post-traumatic stress

disorder

F43.2x, Adjustment disorder

F43.8, Other

reactions to stress (trauma)

F43.9, Reaction to severe stress,

unspecified

T74.x, Child maltreatment, confirmed

T76.x, Child maltreatment, suspected

Z92.49, History

of psychological trauma

Resources

Information & Support

Related material on the Medical Home Portal:

For Professionals

Poverty & Child Health: Practice Tips (AAP)

A succinct guide to screening for basic social needs and connecting families to community resources - includes suggested screening

tools; American Academy of Pediatrics.

Helping Foster and Adoptive Families Cope with Trauma: A Guide for Pediatricians (AAP) ( 3.6 MB)

3.6 MB)

Designed to strengthen clinicians' abilities to identify traumatized children, educate families about toxic stress, and empower

families to respond to children’s behavior in ways that acknowledge past traumas but promote the learning of adaptive reactions

to stress; American Academy of Pediatrics.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (CDC)

Extensive information and resources pertaining to ACEs, including the original CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences

(ACE) Study; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Tackling Toxic Stress (Harvard University)

A series of articles that re-thinks services for children and families based on the science of early childhood development

and an understanding of the consequences of adverse early experiences and toxic stress; Center on Developing Child.

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN)

In-depth information about trauma-informed clinical interventions, screening and assessment practices, disaster behavioral

health response and recovery, culture and trauma, and more.

Child Welfare Information Gateway (HHS)

Connects child welfare and related professionals to comprehensive resources; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

For Parents and Patients

What is Child Traumatic Stress? (NCTSN)

Education and questions and answers about child traumatic stress; National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Therapist Certification Program)

Learn about and find a TF-CBT therapist.

Prevent Child Abuse America

Nonprofit organization that provides information to help providers and parents help prevent child abuse.

Practice Guidelines

Garner A, Yogman M.

Preventing Childhood Toxic Stress: Partnering With Families and Communities to Promote Relational Health.

Pediatrics.

2021;148(2).

PubMed abstract

This revised policy statement on childhood toxic stress acknowledges a spectrum of potential adversities and reaffirms the

benefits of an ecobiodevelopmental model for understanding the childhood origins of adult-manifested disease and wellness.

It also endorses a paradigm shift toward relational health because safe, stable, and nurturing relationships not only buffer

childhood adversity when it occurs but also promote the capacities needed to be resilient in the future.

Keeshin B, Forkey HC, Fouras G, MacMillan HL.

Children Exposed to Maltreatment: Assessment and the Role of Psychotropic Medication.

Pediatrics.

2020.

PubMed abstract

A clinical report that focuses on 2 key issues necessary for the care of maltreated children and adolescents in pediatric

settings: trauma-informed assessments and the role of pharmacotherapy in maltreated children and adolescents.

Patient Education

Trauma-Informed Patient Education (Children's Hospital of Philadelphia)

Downloadable patient education to help: parents help their children cope, children and teens cope with injury and pain or

dealing with traumatic stress reminders, and siblings cope with their brother's or sister's hospitalization, illness, injury,

and recovery. Also includes workbooks for coping with hospitalization.

SEEK Parent Handouts (University of Maryland)

Information for parents about depression, substance abuse, discipline, stress, intimate partner violence, and food insecurity.

Includes lists of national hotlines and other resources.

Tools

Eliciting Parental Strengths and Needs Checklist (Bright Futures) ( 335 KB)

335 KB)

A 7-item checklist to help identify what family concerns should be included in the primary care visit; from the American Academy

of Pediatrics.

Services for Patients & Families in Rhode Island (RI)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | RI | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NM | NV | UT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Abuse Counseling | 1 | 27 | ||||||

| Family Counseling | 44 | 1 | 23 | 69 | ||||

| Foster/Kinship Care | 13 | 2 | 7 | 13 | 25 | |||

| Mental Health Evaluation/Assessment | 24 | 8 | 9 | 131 | ||||

| State Abuse/Neglect Agencies | 1 | 1 | 3 | 49 | ||||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Studies

Implementing an Intervention to Address Social Determinants of Health in Pediatric Practices (PROSWECARE)

Studies looking at better understanding, diagnosing, and treating this condition; from the National Library of Medicine.

Helpful Articles

Garner AS, Shonkoff JP.

Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong

health.

Pediatrics.

2012;129(1):e224-31.

PubMed abstract

Reaffirmed in 2016, this policy statement explains how the effective reduction of toxic stress in young children could be

advanced considerably by pediatricians.

Shonkoff JP, Garner AS.

The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress.

Pediatrics.

2012;129(1):e232-46.

PubMed abstract

Reaffirmed in 2016, this technical report presents a framework that illustrates how early experiences and environmental influences

can leave a lasting signature on the genetic predispositions that affect emerging brain architecture and long-term health.

The report also examines extensive evidence of the disruptive impacts of toxic stress.

Eismann EA, Theuerling J, Maguire S, Hente EA, Shapiro RA.

Integration of the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model Across Primary Care Settings.

Clin Pediatr (Phila).

2019;58(2):166-176.

PubMed abstract

This research assesses the generalizability, barriers, and facilitators of implementing the Safe Environment for Every Kid

(SEEK) model for addressing psychosocial risk factors for maltreatment across multiple primary care settings.

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS.

Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood

Experiences (ACE) Study.

Am J Prev Med.

1998;14(4):245-58.

PubMed abstract

Describes the relationship between the breadth of exposure to abuse or household dysfunction during childhood and multiple

risk factors for several of the leading causes of death in adults.

Authors & Reviewers

| Author: | Zainab Kagen, MD |

| Reviewer: | Brooks Keeshin, MD |

| 2020: update: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPA; Brooks Keeshin, MDR |

| 2020: update: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPA; Brooks Keeshin, MDR |

| 2015: first version: Chuck Norlin, MDA |

Page Bibliography

Eismann EA, Theuerling J, Maguire S, Hente EA, Shapiro RA.

Integration of the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model Across Primary Care Settings.

Clin Pediatr (Phila).

2019;58(2):166-176.

PubMed abstract

This research assesses the generalizability, barriers, and facilitators of implementing the Safe Environment for Every Kid

(SEEK) model for addressing psychosocial risk factors for maltreatment across multiple primary care settings.

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS.

Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood

Experiences (ACE) Study.

Am J Prev Med.

1998;14(4):245-58.

PubMed abstract

Describes the relationship between the breadth of exposure to abuse or household dysfunction during childhood and multiple

risk factors for several of the leading causes of death in adults.

Garner A, Yogman M.

Preventing Childhood Toxic Stress: Partnering With Families and Communities to Promote Relational Health.

Pediatrics.

2021;148(2).

PubMed abstract

This revised policy statement on childhood toxic stress acknowledges a spectrum of potential adversities and reaffirms the

benefits of an ecobiodevelopmental model for understanding the childhood origins of adult-manifested disease and wellness.

It also endorses a paradigm shift toward relational health because safe, stable, and nurturing relationships not only buffer

childhood adversity when it occurs but also promote the capacities needed to be resilient in the future.

Garner AS, Shonkoff JP.

Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong

health.

Pediatrics.

2012;129(1):e224-31.

PubMed abstract

Reaffirmed in 2016, this policy statement explains how the effective reduction of toxic stress in young children could be

advanced considerably by pediatricians.

Keeshin B, Forkey HC, Fouras G, MacMillan HL.

Children Exposed to Maltreatment: Assessment and the Role of Psychotropic Medication.

Pediatrics.

2020.

PubMed abstract

A clinical report that focuses on 2 key issues necessary for the care of maltreated children and adolescents in pediatric

settings: trauma-informed assessments and the role of pharmacotherapy in maltreated children and adolescents.

Rolon-Arroyo B, Oosterhoff B, Layne CM, Steinberg AM, Pynoos RS, Kaplow JB.

The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5 Brief Form: A Screening Tool for Trauma-Exposed Youths.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2020;59(3):434-443.

PubMed abstract

This article summarizes two studies used to develop and validate a brief screen for children and adolescents at risk for developing

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Shonkoff JP, Garner AS.

The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress.

Pediatrics.

2012;129(1):e232-46.

PubMed abstract

Reaffirmed in 2016, this technical report presents a framework that illustrates how early experiences and environmental influences

can leave a lasting signature on the genetic predispositions that affect emerging brain architecture and long-term health.

The report also examines extensive evidence of the disruptive impacts of toxic stress.

Get Help in Rhode Island

Get Help in Rhode Island