Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

Overview

- Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) involves a recognizable pattern of dysmorphic features, growth deficiency, structural brain malformations, and neurobehavioral disabilities.

- Partial fetal alcohol syndrome (PFAS) may not involve the obvious growth deficiency or facial abnormalities and frequently goes undetected.

- Alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND) involves behavioral and/or cognitive deficits, but normal growth and structural development.

- Alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD) involves the facial dysmorphology and other structural anomalies of FAS, but no growth or development issues.

FASDs are diagnoses of exclusion and usually require a multidisciplinary evaluation to ensure accurate diagnosis. Confirming maternal alcohol use is one of the biggest challenges and is not required by some criteria. Early identification, referral, and intervention are especially important for improving long-range outcomes. Fetal alcohol exposure is among the most preventable causes of common neurodevelopmental disabilities. At this time, scientific consensus is that NO amount of alcohol during pregnancy is safe. [Ramsay: 2010]

Other Names & Coding

Q86.0, fetal alcohol syndrome (dysmorphic)

P04.3, newborn affected by maternal use of alcohol

No specific ICD-10 codes exist currently for PFAS, ARND, or ARBD.

Prevalence

Genetics

Prognosis

The unremarkable physical appearance of some affected children who have an intelligence quotient (IQ) that exceeds 70 and do not meet full criteria for FAS often belies their significant cognitive and behavioral challenges. A study of these children, who often are not linked to services, showed higher risk for delinquency, alcohol, and drug abuse. [Streissguth: 2004] Significant numbers of children in the foster and adoptive care systems may have FASDs.

Early identification, individually tailored interventions, and prevention of secondary disabilities hold the greatest potential for optimizing outcomes and minimizing common behavioral manifestations and the associated shame and anger that often accompanies them. [Streissguth: 1997] Early action remains challenging, especially when adoptive parents may not recognize neurodevelopmental impairments that warrant intervention and biological parents may be suffering from alcohol dependency, social stigmatization, economic marginalization, mental health issues, or an FASD of their own.

Practice Guidelines

The American Academy of Pediatrics has recently updated clinical guidelines for the diagnosis of FASDs. Additional guidelines

have been developed by the Institute of Medicine, University of Washington, Canada, and the National Center for Birth Defects

and Developmental Disabilities and are also helpful when considering the diagnosis.

Hoyme HE, May PA, Kalberg WO, Kodituwakku P, Gossage JP, Trujillo PM, Buckley DG, Miller JH, Aragon AS, Khaole N, Viljoen

DL, Jones KL, Robinson LK.

A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 Institute of Medicine

criteria.

Pediatrics.

2005;115(1):39-47.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Bertrand J, Floyd LL, Weber MK.

Guidelines for identifying and referring persons with fetal alcohol syndrome.

MMWR Recomm Rep.

2005;54(RR-11):1-14.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Chudley AE, Conry J, Cook JL, Loock C, Rosales T, LeBlanc N.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis.

CMAJ.

2005;172(5 Suppl):S1-S21.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Roles of the Medical Home

- Learning difficulties

- Developmental problems

- Growth restrictions

- Behavioral concerns

- School failure

- Involvement in foster care or adoption process

The main goal of management is to minimize the impact of FASDs on development, function, and the family through behavioral, educational, and therapeutic strategies. Children with FASDs also need routine preventive care, treatment of acute illnesses, and management of co-occurring medical and psychiatric issues that is informed by knowledge of their diagnosis. FASDs can affect adherence and ability to follow through on recommendations.

Collaborating with educational providers to improve behavior and the individual’s capacity in school is especially important. Connecting caregivers with local support groups, as well as online and other resources, can empower them to nurture successfully and advocate effectively. Universal prevention that addresses attitudes about the consumption of alcohol and pregnancy is key to reducing the incidence of FASDs.

Clinical Assessment

Overview

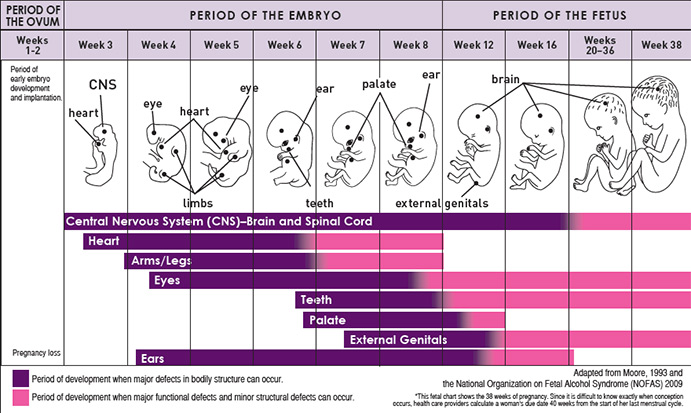

Fetus Vulnerability during Different Times in Pregnancy to Alcohol Exposure

Pearls & Alerts for Assessment

International adoptees and children in foster careClinicians should consider FASDs when they care for children who are international adoptees or in foster care, especially when the child exhibits poor growth. [Miller: 2009]

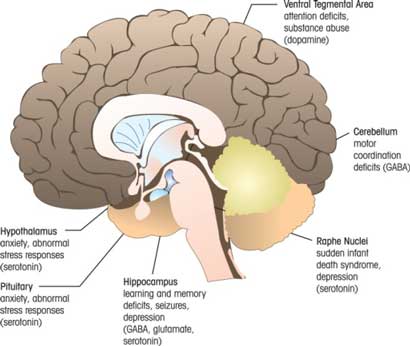

Brain dysfunctionThe degree of facial dysmorphology is associated with the degree of brain dysfunction. [Ervalahti: 2007]

Congenital heart disordersThe congenital heart conditions found in children with FASDs, such as conotruncal defects and ventricular septal defects, are also common in the general population. If the individual has a rare congenital heart disorder, consider conditions other than FASDs.

Early identificationEarly identification of children with FASDs allows for early developmental intervention and other therapeutic services. It also can lead to substance abuse intervention with the child’s mother, possibly prior to a subsequent pregnancy. The diagnosis of FAS, and especially other FASD diagnoses, is more easily made after the newborn period when the behavioral and/or facial features become more evident and, in the case of FAS, before adolescence when the facial features may become less obvious.

History and diagnosisWhile a history of drinking alcohol during pregnancy is useful, it is not necessary to make the diagnosis of FAS or PFAS. Maternal alcohol intake during pregnancy is required to make the diagnosis of ARND or ARBD. FASDs may occur in conjunction with other diagnoses.

Screening

Of Family Members

Mothers can be screened for concerning alcohol use with the CAGE Questionnaire (

73 KB) or T-ACE Questionnaire (

73 KB) or T-ACE Questionnaire ( 64 KB) and referred for support. This screening is ideally performed before a woman becomes pregnant.

64 KB) and referred for support. This screening is ideally performed before a woman becomes pregnant.

For Complications

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): The Vanderbilt Assessment Scales - Parent and Teacher Initial and Follow-Up Scales with Scoring Instructions (NICHQ) (

1.1 MB) has initial and follow-up assessments for teacher and parent informants.

1.1 MB) has initial and follow-up assessments for teacher and parent informants.

-

Mental health issues: The Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) and Youth Report (Y-PSC) (

47 KB)

facilitates recognition of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral

problems. It includes a 35-item checklist for parents or youth and

scoring instructions. (Alternative fee-based tools include the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) and those found in the Bright Futures in Practice: Mental Health—Volume II, Tool Kit).

47 KB)

facilitates recognition of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral

problems. It includes a 35-item checklist for parents or youth and

scoring instructions. (Alternative fee-based tools include the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) and those found in the Bright Futures in Practice: Mental Health—Volume II, Tool Kit).

- Substance abuse: Car, Relax, Alone, Friends, Forget, Trouble (CRAFFT 2.1/2.1+N) is a 6-question behavioral health screen for adolescents at high risk for alcohol and other drug use disorders.

Presentations

Diagnostic Criteria

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) 1996 criteria, revised and clarified [Hoyme: 2005]

These criteria are more inclusive than others, allowing consideration of a diagnosis of FAS and PFAS when children display a characteristic phenotype, but prenatal alcohol exposure cannot be confirmed. The IOM criteria introduced and classified ARND and ARBD and clarified assignment of diagnosis in a clinical setting. This diagnostic system separates affected children according to confirmed alcohol exposure, presence of characteristic dysmorphic features, growth restriction, and neurocognitive problems.

The University of Washington system [Center: 2014]

This diagnostic system is more exclusive, requiring the complete phenotype for FAS. It introduced the lip philtrum pictorial guide (Facial Features Associated with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (University of Washington)) that is used by all of the systems. The coding scheme uses a Likert scale rating of 1 (no involvement) to 4 (maximal involvement) in 4 domains: 1) facial features, 2) growth restriction, 3) central nervous system damage, and 4) alcohol exposure. The findings in each domain are numerically organized into a “4-digit diagnostic code” with 256 possible combinations arranged in 22 categories. FAS Diagnostic and Prevention Network provides more details.

Fetal alcohol syndrome: guidelines for referral and diagnosis [Barry: 2004]

This effort focuses on unifying the various diagnostic criteria for FAS, but defers classification of less severe presentations.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis [Chudley: 2005]

This system proposes evaluating children according to the “4-digit diagnostic code” used by the University of Washington system and describing the children according to the Institute of Medicine categories, thus harmonizing the 2 diagnostic systems commonly used in the United States. (Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: Canadian Guidelines for Diagnosis)

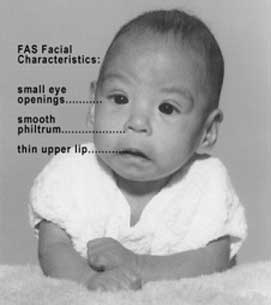

Clinical Classification

- Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS): Typical facial features (shortened palpebral fissures, indistinct philtrum, thin upper lip), prenatal or postnatal retardation of height or weight (<10 percentile), plus structural brain defects or microcephaly. Diagnosis is further differentiated by whether prenatal alcohol exposure is confirmed.

- Partial fetal alcohol syndrome (PFAS): Fewer physical findings associated with full FAS, plus otherwise unexplained behavioral and/or cognitive abnormalities. Diagnosis is further differentiated by whether prenatal alcohol exposure is confirmed.

-

Alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD): Confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure, 2 or more of the characteristic facial findings of FAS, plus at least 1 other major

or 2 minor structural defects, as listed:

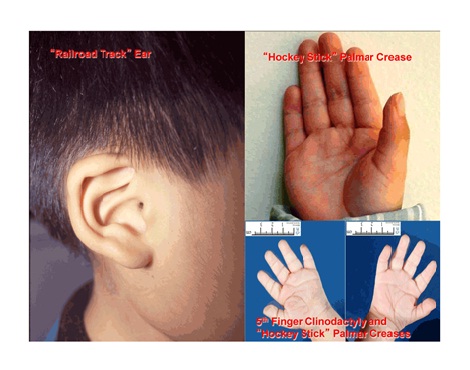

Structural Defects Considered "Major"Atrial septal defect Ureteral duplication Aberrant great vessels Strabismus Ventricular septal defect Ptosis Conotruncal heart defects Retinal vascular anomalies Radoulnar synostosis Optic nerve hypoplasia Vertebral segmentation defects Conductive hearing loss Large joint contractures Sensorineural hearing loss Scoliosis “Horshoe” kidney Aplastic hypoplastic Dysplastic kidneys

Structural Defects Considered "Minor"Hypoplastic nails Camptodactyly Short fifth digit “Hockey stick” palmar crease Clinodactly of fifth digit Refractive errors Pectus carinatum or excavatum “Railroad track” ears

- Alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND): Confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure, structural brain abnormalities or microcephaly, plus otherwise unexplained behavioral and cognitive abnormalities that result in significant impairment.

Neurobehavioral Disorder Associated with Prenatal Alcohol Exposure (ND-PAE) is a “Condition for Further Study" in the DSM-5 Handbook of Differential Diagnosis (APA).The intent of this new designation is to better capture the behavioral and mental health effects of in utero exposure to alcohol of individuals with and without physical dysmorphia, in contrast to ARND, which applies only to individuals with neurobehavioral effects in the absence of physical dysmorphia effects. [Hagan: 2016]

Differential Diagnosis

43 KB), from [Barry: 2004], provides a table of overlapping and differentiating

physical features. Also, please see the Portal's page about Missing issue with id: 1c2942e5.xml.

43 KB), from [Barry: 2004], provides a table of overlapping and differentiating

physical features. Also, please see the Portal's page about Missing issue with id: 1c2942e5.xml.

Comorbid & Secondary Conditions

Mental illness: One study showed that of the group of adults with known maternal alcohol exposure: [Famy: 1998]

- 92% met criteria for at least 1 DSM-IV Axis 1 diagnosis

- 44% met criteria for major depressive disorder (The Portal's Depression provides assessment and management information.)

- 20% met criteria for bipolar 1 disorder

- 40% met criteria for psychotic disorders (brief psychotic disorder was included)

Congenital cardiac and renal malformations are more common in children with FASDs. Specific cardiac, renal, ophthalmic, otic, skeletal, dermatologic, and sensory abnormalities are among the findings included in criteria for ARBD and ARND. [Hoyme: 2005]

History & Examination

- Renal: aplastic/hypoplastic/dysplastic kidneys, “horseshoe” kidneys/ureteral duplications

- Eyes: strabismus, ptosis, retinal vascular anomalies, optic nerve hypoplasia, refractive errors

- Ears: conductive hearing loss, neurosensory hearing loss, “railroad track” ears

- Skeletal: radioulnar synostosis, vertebral segmentation defects, large joint contractures, scoliosis, pectus carinatum/excavatum, short fifth digits, clinodactyly of fifth fingers, camptodactyly.

- Other minor anomalies: hypoplastic nails, “hockey stick” palmar creases

- Unusual physiologic responses: sleep issues, hyper-responsiveness to sensory stimuli, sensory aversions

Current & Past Medical History

Family History

Pregnancy/Perinatal History

Knowing the general drinking habits prior to pregnancy can assist with obtaining accurate reports of drinking before pregnancy was recognized. The “Timeline Followback Method” may elicit the most accurate maternal drinking history. This method uses visual prompts, such as calendars and key life events like holidays, to trigger accurate recall of alcohol use. (Timeline Followback Sample Calendar and Instructions (Nova Southeastern University))

Confirming a maternal drinking history is notoriously difficult and may be impossible for children who are adopted or in foster care. Because use of alcohol during pregnancy is usually a sensitive topic, questions should be asked non-judgmentally. Working to create mutual trust and respect, practicing empathy, and using accepting body language can help individuals feel safe in revealing risky behavior, painful family behavioral histories, and stigmatizing or sensitive information. Open-ended questions, such as “Please help me understand more about your family in relation to alcohol and drugs,” are often helpful.

Developmental & Educational Progress

Maturationalprogress

Social & Family Functioning

Physical Exam

Many children with FASDs demonstrate one or more characteristic facial feature. A “gestalt” diagnosis (not advised) must be confirmed with a detailed physical and neuropsychological evaluation. Physical assessment of children with prenatal alcohol exposure can be learned by primary care clinicians. Jones, et al. found that after a 2-day interactive training, pediatricians were able to identify accurately the growth delays and dysmorphic facial features characteristic of children with FASDs. [Jones: 2006]

General

Vital Signs

Growth Parameters

Information about prenatal and postnatal growth (height, weight, and head circumference) should be documented. Psychotropic medications may affect appetite and, subsequently, weight. Head circumference is generally at or below the 10th percentile. The CDC recommends plotting growth on the World Health Organization (WHO) charts for ages 0-2 and the CDC charts for 2-18 year olds. (Growth Charts for Ages 0-2 Years (WHO) and for Ages 2-18 (CDC))

Skin

HEENT/Oral

In FAS, at least 2 of the following cardinal minor malformations of the face must be present:

- Short palpebral fissures (at or below 10th percentile)

- Thin vermillion border of the upper lip

- Smooth philtrum

- Mid-face hypoplasia

- Railroad Track Ears (link leads to Google images)

- Strabismus, ptosis, retinal vascular anomalies, optic nerve hypoplasia

- Epicanthal Folds (link leads to MedlinePlus image)

- Flat nasal bridge

- Anteverted Nares (link leads to National Human Genome Research Institute images)

- Long philtrum

Heart

Listen for cardiac murmur. Common defects in children with FASDs include atrial septal defects, aberrant great vessels, ventricular septal defects, and/or conotruncal defects.

Extremities/Musculoskeletal

Among other malformations consistent with FASDs but not diagnostic are:

- Hypoplastic nails

- Decreased pronation/supination of the elbow - radioulnar synostosis

- Clinodactyly of the 5th fingers

- Large joint contractures

- Camptodactyly

- “Hockey stick” palmar creases (link leads to Google images)

Testing

Sensory Testing

Imaging

Genetic Testing

Other Testing

- Global cognitive deficit (decreased IQ or developmental delay in those too young for formal IQ assessment)

- Cognitive deficits or significant developmental discrepancies (e.g., specific learning disabilities, especially math and/or visual-spatial deficits)

- Executive function deficits

- Motor functioning delays or deficits (gross and/or fine motor)

- Attention and hyperactivity problems

- Social skills problems

- Other domains that include sensory deficits, pragmatic language problems, memory deficits, and difficulty responding to common parenting practices

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Clinics (see RI providers [0])

Medical Genetics (see RI providers [4])

Developmental - Behavioral Pediatrics (see RI providers [12])

Pediatric Otolaryngology (ENT) (see RI providers [7])

Pediatric Ophthalmology (see RI providers [8])

Pediatric Nephrology (see RI providers [10])

Pediatric Cardiology (see RI providers [17])

Psychiatry/Medication Management (see RI providers [80])

Treatment & Management

Overview

Developmental and educational progress are the areas predominantly affected by FASDs and should be followed in a structured fashion to identify problems early. These areas can be divided into cognitive and behavioral domains. Though no “magic bullet” exists to fix the problems encountered by children with FASDs, interventions are evolving to help manage specific aspects of the condition.

Pearls & Alerts for Treatment & Management

Treating ADHD in children with FASDsAlthough stimulant medications may be less effective for treating ADHD in children with FASDs, no other medications seem more effective. Because ADHD contributes to many functional problems, managing the side effects of stimulants (including reduced appetite) is usually attempted before discontinuing this medication class. For children who experience excessive anxiety or moodiness on stimulants, switching to an alpha-2 agonist can be an option; these may be particularly helpful for children whose most problematic symptoms related to ADHD are hyperactivity and impulsivity.

Hidden nature of FASDsA challenging aspect of FASDs for older children is the “hidden” nature of the disorder and its specific disabilities. Affected individuals can give the impression of being more capable than they really are, understanding more than they do, or seeming to master material (but then forgetting it).

How should common problems be managed differently in children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders?

Growth or Weight Gain

Bacterial Infections

Systems

Development (general)

- Infants: Sensory and regulatory problems are common. Poor sleep-wake cycles, irritability, failure to thrive, and nursing difficulties are reported frequently.

- Toddlers and preschoolers: Common issues include fine and gross motor delays, failure to comply with parental or other authority, loss of previous learning, poor sleep patterns, and toileting difficulties. Children may be fidgety, easily distracted, or unable to focus attention. Sensory issues might emerge or become more pronounced, like hypersensitivity to certain food textures, sounds, and fabrics.

- School-age children: While school-age children may have neurocognitive deficits across all areas and domains of function, attention problems are particularly common. Executive functioning deficits become more apparent as children are expected to learn more abstract concepts, including understanding cause-and-effect relationships and learning from mistakes. Visual-spatial abilities and math skills are often weak. Social skill deficits (e.g., understanding social boundaries, reading social cues, and relating to peers) become more apparent as children age.

- Adolescents: The cognitive, behavioral, and functional problems associated with FASDs usually persist and may be magnified, putting teens at risk for any combination of anxiety, depression, poor self-esteem, and substance abuse.

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Clinics (see RI providers [0])

Medical Genetics (see RI providers [4])

Developmental - Behavioral Pediatrics (see RI providers [12])

Early Intervention for Children with Disabilities/Delays (see RI providers [13])

Physical Therapy (see RI providers [7])

Occupational Therapy (see RI providers [22])

Speech - Language Pathologists (see RI providers [34])

Learning/Education/Schools

- Intellectual ability: Individuals with FAS have lower intelligence quotients (IQs) than those with other FASD diagnoses. Lower IQs with or without facial abnormalities, and normal IQs with facial abnormalities contribute to the complexities of recognizing FASDs. IQs for those with FASDs may vary in individuals, but is stable over time. [Streissguth: 2004]

- Attention and processing speed: Infants, children, and adolescents have slower processing speed. More specifically, school-age children have deficient processing speed when performing tasks that require effortful (rather than automatic) processing. Infants also have decreased visual reaction time. Continuous performance tests indicate vigilance impairment. These individuals also have difficulty with response inhibition and problems with aspects of attention, investment, organization, and maintenance.

- Executive functioning: Children with FASDs often have impaired executive functioning that affects their ability to complete tasks that require sustained effort. Overall, these individuals struggle with cognitive planning and use ineffective strategies for problem solving. They have impairment in working memory, response inhibition, and difficulty altering behavior in response to reinforcement contingencies. Nonverbal and verbal fluency tend to be problematic (e.g., generation of words beginning with certain letters under specific constraints).

- Visual perception and visual construction: Visual perception is typically normal unless the individual is performing a task that requires integration of information (e.g., planning and visual motor). IQ may correlate with a person’s ability to integrate information, especially shifting attention from global to local features. Visual construction may be markedly impaired. These deficits can cause children to misunderstand gestures in communication. They can affect handwriting and cause problems with social perception.

- Learning and memory: Conditioning and habituation is diminished in infants. Children struggle with delayed object recall, but not immediate object recall. Delayed free recall is affected but not delayed recognition, which is attributed to problems with encoding rather than memory. Once established, the retention of memory is comparable to typical individuals, though those with FASDs may require alternative teaching methods or more trials to ensure mastery. In general, both visual and verbal learning and memory are impaired.

- Number processing: Individuals with FASDs struggle with number processing, which stems from deficits with calculation and cognitive estimation rather than deficits with the simpler tasks of reading and writing numbers.

These interventions address cognitive and executive functioning impairments that can interfere with learning and appropriate classroom behavior. Deficits in verbal and spatial learning, planning, working memory, cognitive flexibility, inhibition, problem solving, reading, spelling, and math call for teaching strategies and classroom modifications:

- Cognitive control therapy (CCT): Teaches strategies for acquiring and organizing information. [Santostefano: 1988] Key areas targeted include 1) being more aware of body position and movements; 2) focal attention through scanning and then prioritizing information; 3) processing information while distracting stimuli are present; 4) controlling external information; and 5) categorizing information. In one study, children who completed CCT were reported by teachers to have improved classroom behavior, academic achievement, writing skills, self-confidence, and a better attitude toward school and learning.

- Language and literacy training: Focuses on enhancing pre-literacy and early literacy skills in 9-year-olds with FASDs. [May: 2009] [Adnams: 2007]

- Self-regulation intervention: Focuses on enhancing self-regulation skills and improving executive functioning deficits in 6- to 11-year-old children with FASDs who have been adopted or are in foster care. [Bertrand: 2009] The Medical Home Portal's Foster Care has more information.

- Mathematics training: Focuses specifically on math learning disabilities, which are common in children with FASDs. Before being assigned to treatment or control arms, caregivers attend 2 workshops to learn about FASDs and receive instructions on promoting positive behavioral regulation skills in their children. [Kable: 2007]

- Working-memory strategies: Teaches rehearsal strategies to improve working memory. For example, with rehearsal training children are first tested with a digit span memorization task. Afterward, the children are taught to “keep whispering the names of the items (or digits) over and over in your head.” In this way, children “rehearse” the information, making it easier to later recall. There is behavioral and caregiver-reported evidence that children who are specifically taught to rehearse in this way will later demonstrate spontaneous use of this technique for working memory tasks. [Loomes: 2008]

- Behavioral intervention: Some children with an FASD and significantly disruptive behavior may be placed in a classroom setting with an emphasis on behavioral management that uses a clear, concrete, positive reinforcement schedule to shape behaviors into more appropriate interactions with peers and adults.

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

School Districts (see RI providers [64])

Mental Health/Behavior

- Social skills interventions: Children's Friendship Training group therapy teaches social skills to help affected children be accepted by peers. Skills includes interacting with peers in a way that leads to common-ground activities, peer entry, and play; parent receive instruction in peer network formation. [O'Connor: 2006]

- Safety skills interventions: Computer games are used to teach fire and street safety. [Coles: 2007]

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Special Education/Schools (see RI providers [35])

Family

2.5 MB). In this model, the stress of raising a child with a disability is a

function of child’s characteristics, parental perception of the child’s

disability, and access to resources within and outside the family. Of

children with FASDs, only around 15-20% are being raised by their biological

parents; most are raised by foster or adoptive parents who may be extended

biological family members. Another unique stressor is the difficulty in

obtaining an FASD diagnosis, particularly when key facial features and a

history of maternal drinking during pregnancy are lacking. The diagnosis is

key to accessing many services. Children with FASDs may also face the

problem of “an invisible disability” because their intellectual impairment

is not made apparent by physical characteristics.

2.5 MB). In this model, the stress of raising a child with a disability is a

function of child’s characteristics, parental perception of the child’s

disability, and access to resources within and outside the family. Of

children with FASDs, only around 15-20% are being raised by their biological

parents; most are raised by foster or adoptive parents who may be extended

biological family members. Another unique stressor is the difficulty in

obtaining an FASD diagnosis, particularly when key facial features and a

history of maternal drinking during pregnancy are lacking. The diagnosis is

key to accessing many services. Children with FASDs may also face the

problem of “an invisible disability” because their intellectual impairment

is not made apparent by physical characteristics. In one study, 95% of parents of children with an FASD scored at or above the 90th percentile for parenting stress, particularly on measures of severity of difficult behaviors, negative parent-child interactions, and pessimism related to the child’s future ability to become independent. [Watson: 2013] A study that included biological mothers who retained custody of their FASD-affected children found shame, guilt, and judgment as unique contributors to stress. Adoptive families in the same study described grief, which was exacerbated if they were not aware of the alcohol exposure at the time of adoption. [Sanders: 2010]

Children with FASDs often have tantrums and display aggression and destructive behaviors. Because contingency learning is often poor, the logical consequences used to manage behavior in neurotypical children are largely ineffective. Learning and memory are also often affected, making rigid routines and frequent cueing necessary to teach the basic activities of daily living. This adds to frustration because of the need to teach and re-teach the same skills (e.g., how to tie shoes).

As children become adolescents, new social problems tend to manifest first at school. Children who are socially disinhibited and have poor executive functioning may want to connect with others, but be easily drawn to social groups and other children who have behavioral problems. The child with an FASD can then have difficulty evaluating the consequences of actions that peers encourage (e.g., buying cigarettes for peers in order to make friends). Individuals with an FASD are at much higher risk for legal troubles.

Parent-focused interventions equip caregivers with strategies to reduce stress, increase self-efficacy, and foster more positive parent-child relationships. Structure, brevity, and persistence are key when working with children with FASDs. Although each child is unique, the following tips can be helpful (for neurotypical kids also):

- Concentrate on the child’s strengths and talents.

- Accept the child’s limitations.

- Be consistent with everything (discipline, school, behaviors).

- Use concrete language and examples.

- Use stable routines that do not change.

- KIS: Keep it simple.

- Be specific, say exactly what you mean.

- Structure the child’s world to provide predictability and consistency.

- Use visual aids, music, and hands-on experience to assist with the learning process.

- Supervise friends, visits, routines.

- Repeat, repeat, repeat.

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Clinics (see RI providers [0])

General Counseling Services (see RI providers [30])

Ears/Hearing

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Audiology (see RI providers [24])

Pediatric Otolaryngology (ENT) (see RI providers [7])

Special Education/Schools (see RI providers [35])

Immunology/Infectious Disease

Nutrition/Growth/Bone

Typically, but not universally, higher degrees of growth restriction and dysmorphology coincide with increased severity of neurodevelopmental disability. [Ervalahti: 2007] Poor growth and weight gain could pose concern when treating ADHD, since stimulant medications frequently reduce appetite and resultant weight loss. Boosting Calories for Babies, Toddlers, and Older Children the child’s diet can help while maintaining effective dosages of medication. Although underweight tends to persist in children who meet FAS criteria, those with PFAS/ARND diagnoses have higher rates of overweight and obesity by adolescence. [Fuglestad: 2014] Management information can be found in the Portal’s Missing link with id: 99e6f817.xml.

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Pediatric Orthopedics (see RI providers [16])

Pediatric Gastroenterology (see RI providers [18])

Dieticians and Nutritionists (see RI providers [3])

Pharmacy & Medications

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Developmental - Behavioral Pediatrics (see RI providers [12])

Psychiatry/Medication Management (see RI providers [80])

Sleep

Encouragement and maintenance of sleep hygiene are first-line treatments while keeping in mind that children with FASDs are less able to adapt to even minor changes. [Jan: 2010] Consistent bedtimes and related activities can be helpful. Deficient or inappropriate functioning of melatonin in children with FASDs suggest consideration of melatonin therapy. [Wasdell: 2008]

See Behavioral Techniques to Improve Sleep and Medical Conditions Affecting Sleep in Children for further details.

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Sleep Disorders (see RI providers [2])

Transitions

Some of the services for which individuals with an FASD diagnosis might qualify:

- Supported employment/job coach (Disability Related Employment Programs (see RI providers [18]))

- Transportation (Disability Related Transportation (see RI providers [12]))

- Assisted living (Independent Living Arrangements & Skills (see RI providers [25]))

- Respite care (Crisis/Respite Care (see RI providers [13]))

- Social Security disability benefits (see Funding Your Child's Special Needs)

- Supplemental Security Income (SSI/SSDI (see RI providers [10]))

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Family Medicine (see RI providers [71])

Ask the Specialist

How does one distinguish FASDs from Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)?

Children with FASDs are usually more able than autistic children to use gestures and nonverbal communication to interact, demonstrate empathy, and express enjoyment in social overtures. ASD and FASDs differ in their characteristic patterns of cognitive disability. One study found that 79% of children with ASD had a higher nonverbal than verbal IQ; the opposite was true for children with FASDs. [Bishop: 2007] For more details, see Missing issue with id: 1c2942e5.xml.

How can I help to optimize education for children with FASDs?

Establishing appropriate expectations based on formal neurocognitive evaluations sets the child up to succeed. Caregivers will need to reduce distractions, express concrete directions, and manage disruptive behaviors through a systematic, child-specific behavior plan that provides positive reinforcement for desired behaviors.

What medications treat FASDs?

No medications treat the underlying injury of FASDs, rather medications target comorbidity that can have a substantial impact of a child’s functioning and quality of life.

What promising treatments are on the horizon for children with an FASDs?

The National Institutes of Health – National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) published 2 reviews of promising interventions for children with FASD in 2011. The behavioral interventions detailed in the review by [Paley: 2011] have been shown to improve function in school-aged children affected by FASD. The review by [Idrus: 2011] highlights biochemical interventions that target the underlying mechanisms of prenatal alcohol-induced brain damage or enhance CNS plasticity during or after exposure. Their findings, from animal models only, are not clinically available.

Resources for Clinicians

On the Web

FASD: Guidelines for Referral and Diagnosis (CDC) ( 612 KB)

612 KB)

Provides information about diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, referral considerations, services, and prevention;

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in coordination with the National Task Force on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Fetal

Alcohol Effects, which includes the American Academy of Pediatrics and other groups.

FASD: Information for Healthcare Providers (CDC)

A comprehensive list of articles, patient education, videos, and training for clinicians; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (SAMHSA)

Provides prevention, intervention, and treatment information for behavioral health providers, program administrators, and

clinicians in a 226-page booklet; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Program (AAP)

By navigating the topics on the left-hand side of this webpage, clinicians can find a wealth of information about diagnosis,

referral, patient management, and care coordination.

Helpful Articles

Barry KL, et al.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Guidelines for Referral and Diagnosis.

National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of

Health and Human Services.

2004.

/ http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/documents/FAS_guidelines_accessible.pdf

Detailed information about diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, referral considerations, services, and prevention.

Bertrand J.

Interventions for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs): overview of findings for five innovative research

projects.

Res Dev Disabil.

2009;30(5):986-1006.

PubMed abstract

An overview of a general intervention model and the findings of 5 intervention studies conducted within this framework. Results

revealed a significant treatment effect on a parent report measure of executive functioning.

Riley EP, Infante MA, Warren KR.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: an overview.

Neuropsychol Rev.

2011;21(2):73-80.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Discusses the evolving considerations for diagnosis of FASDs and includes a comparison of the various diagnostic schemas.

Peadon E, Elliott EJ.

Distinguishing between attention-deficit hyperactivity and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in children: clinical guidelines.

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat.

2010;6:509-15.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Examines the relationship between ADHD and FASD and discusses treatments.

Williams JF, Smith VC.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders.

Pediatrics.

2015;136(5):e1395-406.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Focuses on the role of the medical home in prevention, intervention, and treatment of FASDs.

Hagan JF Jr, Balachova T, Bertrand J, Chasnoff I, Dang E, Fernandez-Baca D, Kable J, Kosofsky B, Senturias YN, Singh N, Sloane

M, Weitzman C, Zubler J.

Neurobehavioral Disorder Associated With Prenatal Alcohol Exposure.

Pediatrics.

2016;138(4).

PubMed abstract

Clinical Tools

Assessment Tools/Scales

Dysmorphology Scoring System - FASD

The dysmorphology score is a weighted calculation based on assigning points to clinical findings characteristic of FASDs;

from the Hoyme, et al, 2005 publication "A Practical Clinical Approach to Diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: Clarification

of the 1996 Institute of Medicine Criteria."

FAS Facial Analysis Software (University of Washington)

The software was developed for use by health care and research professionals to measure the magnitude of the diagnostic facial

features of FAS. It then scores the outcomes of these facial measures using the 4-Digit Diagnostic Code.

Facial Features Associated with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (University of Washington)

Photos of FAS facial phenotype across race and photos of a lip philtrum guide.

Growth/BMI Charts

Growth Charts for Ages 0-2 Years (WHO) and for Ages 2-18 (CDC)

Provides links to 2 comprehensive sets of growth charts: the CDC Clinical Growth Charts (preferred for use with children 24

months and older) and the World Health Organization (WHO) Charts (preferred for children under 24 months); Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention.

Questionnaires/Diaries/Data Tools

Timeline Followback Sample Calendar and Instructions (Nova Southeastern University)

Free of charge to help ascertain the level of maternal drinking during pregnancy.

Toolkits

Bright Futures in Practice: Mental Health—Volume II, Tool Kit

Comprehensive set of tools for clinicians and families; addresses mental health in various pediatric age groups; includes

a variety of resources, checklists, intake and assessment forms, and patient education materials.

Patient Education & Instructions

Fetal Alcohol Exposure (NIH) ( 454 KB)

454 KB)

Three-pages of information about the possible consequences of fetal alcohol exposure; National Institutes of Health.

Resources for Patients & Families

Information on the Web

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (CDC)

Comprehensive information about FASDs; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

This nonprofit organization provides a wealth of information and links to local resources and summer camps for children with

FASDs.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (MedlinePlus)

Information for families that includes description, frequency, causes, inheritance, other names, and additional resources;

from the National Library of Medicine.

Frequently Asked Questions About Section 504 and the Education of Children with Disabilities (ED)

Clarifies pertinent requirements of Section 504 and answers more than 40 often-asked questions; U.S. Department of Education.

National & Local Support

Center for Parent Information and Resources

A large resource library related to children with disabilities. Locate organizations and agencies within each state that address

disability-related issues.

Studies/Registries

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders and Children (clinicaltrials.gov)

Studies looking at better understanding, diagnosing, and treating this condition; from the National Library of Medicine.

Services for Patients & Families in Rhode Island (RI)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | RI | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NM | NV | UT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audiology | 24 | 3 | 22 | 8 | 22 | |||

| Crisis/Respite Care | 13 | 2 | 12 | 11 | 37 | |||

| Developmental - Behavioral Pediatrics | 12 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9 | |||

| Dieticians and Nutritionists | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 | |||

| Disability Related Employment Programs | 18 | 5 | 24 | 22 | 74 | |||

| Disability Related Transportation | 12 | 4 | 13 | 32 | 21 | |||

| Early Childhood Mental Health Care | 5 | 5 | 5 | 17 | ||||

| Early Intervention for Children with Disabilities/Delays | 13 | 3 | 34 | 30 | 51 | |||

| Family Medicine | 71 | 8 | 1 | 60 | ||||

| Family Support Services | 45 | 13 | 23 | 66 | 31 | |||

| Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Clinics | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| General Counseling Services | 30 | 1 | 10 | 213 | 298 | |||

| Independent Living Arrangements & Skills | 25 | 1 | 18 | 60 | 92 | |||

| Medical Genetics | 4 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | |||

| Occupational Therapy | 22 | 1 | 17 | 22 | 37 | |||

| Pediatric Cardiology | 17 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 18 | 2 | 5 | 2 | ||||

| Pediatric Nephrology | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Pediatric Ophthalmology | 8 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 4 | |||

| Pediatric Orthopedics | 16 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 10 | |||

| Pediatric Otolaryngology (ENT) | 7 | 1 | 11 | 5 | 10 | |||

| Physical Therapy | 7 | 12 | 9 | 40 | ||||

| Psychiatry/Medication Management | 80 | 3 | 37 | 53 | ||||

| School Districts | 64 | 90 | 4 | 44 | ||||

| Sleep Disorders | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Special Education/Schools | 35 | 3 | 82 | 9 | 43 | |||

| Speech - Language Pathologists | 34 | 4 | 23 | 11 | 65 | |||

| SSI/SSDI | 10 | 4 | 17 | 14 | 11 | |||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Authors & Reviewers

| Authors: | Patrick Shea, MD |

| Deborah Bilder, MD | |

| Lisa M. Ruiz, MD |

| 2015: update: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPA; Meghan S Candee, MD, MScR |

| 2015: first version: Susan Lewin, MDA |

Bibliography

Adnams CM, Sorour P, Kalberg WO, Kodituwakku P, Perold MD, Kotze A, September S, Castle B, Gossage J, May PA.

Language and literacy outcomes from a pilot intervention study for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in South

Africa.

Alcohol.

2007;41(6):403-14.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Barry KL, et al.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Guidelines for Referral and Diagnosis.

National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of

Health and Human Services.

2004.

/ http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/documents/FAS_guidelines_accessible.pdf

Detailed information about diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, referral considerations, services, and prevention.

Bertrand J.

Interventions for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs): overview of findings for five innovative research

projects.

Res Dev Disabil.

2009;30(5):986-1006.

PubMed abstract

An overview of a general intervention model and the findings of 5 intervention studies conducted within this framework. Results

revealed a significant treatment effect on a parent report measure of executive functioning.

Bertrand J, Floyd LL, Weber MK.

Guidelines for identifying and referring persons with fetal alcohol syndrome.

MMWR Recomm Rep.

2005;54(RR-11):1-14.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Bishop S, Gahagan S, Lord C.

Re-examining the core features of autism: a comparison of autism spectrum disorder and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

J Child Psychol Psychiatry.

2007;48(11):1111-21.

PubMed abstract

Burd L, Klug MG, Martsolf JT, Kerbeshian J.

Fetal alcohol syndrome: neuropsychiatric phenomics.

Neurotoxicol Teratol.

2003;25(6):697-705.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Center on Human Development & Disability.

FAS diagnostic and prevention network.

University of Washington; (2014)

https://depts.washington.edu/fasdpn/. Accessed on March 2017.

Includes validation of the FASD 4-Digit Code and other resources.

Chudley AE, Conry J, Cook JL, Loock C, Rosales T, LeBlanc N.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis.

CMAJ.

2005;172(5 Suppl):S1-S21.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis of FAS and its related disabilities, developed by broad-based consultation among experts

in diagnosis.

Coles CD, Strickland DC, Padgett L, Bellmoff L.

Games that work: using computer games to teach alcohol-affected children about fire and street safety.

Res Dev Disabil.

2007;28(5):518-30.

PubMed abstract

In this study, 32 children diagnosed with FASDs learned fire and street safety through virtual world computer games to teach

recommended safety skills. Results suggested that this is a highly effective method for teaching safety skills to high-risk

children who have learning difficulties.

Cooley WC, Sagerman PJ.

Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home.

Pediatrics.

2011;128(1):182-200.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Douzgou S, Breen C, Crow YJ, Chandler K, Metcalfe K, Jones E, Kerr B, Clayton-Smith J.

Diagnosing fetal alcohol syndrome: new insights from newer genetic technologies.

Arch Dis Child.

2012;97(9):812-7.

PubMed abstract

Genetic assessment was of particular value in excluding other diagnoses and providing information to careers.

Ervalahti N, Korkman M, Fagerlund A, Autti-Rämö I, Loimu L, Hoyme HE.

Relationship between dysmorphic features and general cognitive function in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

Am J Med Genet A.

2007;143A(24):2916-23.

PubMed abstract

Study findings imply an inverse relationship between growth deficiency/dysmorphic features and cognitive function in children

with FASD. Although the correlations are significant, the data suggest that in individual cases, the total dysmorphology

score cannot reliably predict cognitive function in later life.

Famy C, Streissguth AP, Unis AS.

Mental illness in adults with fetal alcohol syndrome or fetal alcohol effects.

Am J Psychiatry.

1998;155(4):552-4.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Fuglestad AJ, Boys CJ, Chang PN, Miller BS, Eckerle JK, Deling L, Fink BA, Hoecker HL, Hickey MK, Jimenez-Vega JM, Wozniak

JR.

Overweight and obesity among children and adolescents with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

Alcohol Clin Exp Res.

2014;38(9):2502-8.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Gauthier TW.

Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and the Developing Immune System.

Alcohol Res.

2015;37(2):279-85.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Hagan JF Jr, Balachova T, Bertrand J, Chasnoff I, Dang E, Fernandez-Baca D, Kable J, Kosofsky B, Senturias YN, Singh N, Sloane

M, Weitzman C, Zubler J.

Neurobehavioral Disorder Associated With Prenatal Alcohol Exposure.

Pediatrics.

2016;138(4).

PubMed abstract

Hanlon-Dearman, AC.

Sleep Characteristics of Young Alcohol Affected Children; A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis.

Winnipeg: Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba.

2003.

Hoyme HE, May PA, Kalberg WO, Kodituwakku P, Gossage JP, Trujillo PM, Buckley DG, Miller JH, Aragon AS, Khaole N, Viljoen

DL, Jones KL, Robinson LK.

A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 Institute of Medicine

criteria.

Pediatrics.

2005;115(1):39-47.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Idrus NM, Thomas JD.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: Experimental Treatments and Strategies for Intervention.

Alcohol Research and Health.

2011;34(1).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Jan JE, Asante KO, Conry JL, Fast DK, Bax MC, Ipsiroglu OS, Bredberg E, Loock CA, Wasdell MB.

Sleep Health Issues for Children with FASD: Clinical Considerations.

Int J Pediatr.

2010;2010.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Jones KL, Robinson LK, Bakhireva LN, Marintcheva G, Storojev V, Strahova A, Sergeevskaya S, Budantseva S, Mattson SN, Riley

EP, Chambers CD.

Accuracy of the diagnosis of physical features of fetal alcohol syndrome by pediatricians after specialized training.

Pediatrics.

2006;118(6):e1734-8.

PubMed abstract

Accurate and early diagnosis of the fetal alcohol syndrome is important for secondary prevention, intervention, and treatment,

yet many pediatricians lack expertise in recognition of the characteristic features of this disorder. After a relatively short

training session, pediatricians were reasonably accurate in diagnosing fetal alcohol syndrome on the basis of physical features

and in recognizing most of the selected specific features associated with the disorder.

Kable JA, Coles CD, Taddeo E.

Socio-cognitive habilitation using the math interactive learning experience program for alcohol-affected children.

Alcohol Clin Exp Res.

2007;31(8):1425-34.

PubMed abstract

These findings suggest that parents of children with FASDs benefit from instruction in understanding their child's alcohol-related

neurological damage and strategies to provide positive behavioral supports and that targeted psychoeducational programs may

be able to remediate some of the math deficits associated with prenatal alcohol exposure.

Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, Shaffer HJ.

A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.

1999;153(6):591-6.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Loomes C, Rasmussen C, Pei J, Manji S, Andrew G.

The effect of rehearsal training on working memory span of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

Res Dev Disabil.

2008;29(2):113-24.

PubMed abstract

Rehearsal training was found successful at increasing the memory for numbers among children with FASDs and may help to ameliorate

working memory difficulties in FASDs.

May PA, Gossage JP, Kalberg WO, Robinson LK, Buckley D, Manning M, Hoyme HE.

Prevalence and epidemiologic characteristics of FASD from various research methods with an emphasis on recent in-school studies.

Dev Disabil Res Rev.

2009;15(3):176-92.

PubMed abstract

Miller BS, Kroupina MG, Iverson SL, Masons P, Narad C, Himes JH, Johnson DE, Petryk A.

Auxological evaluation and determinants of growth failure at the time of adoption in Eastern European adoptees.

J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab.

2009;22(1):31-9.

PubMed abstract

National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

Data & Statistics: Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; (2017)

http://www.cdc.gov/NCBDDD/fasd/data.html. Accessed on March 2017.

O'Connor MJ, Frankel F, Paley B, Schonfeld AM, Carpenter E, Laugeson EA, Marquardt R.

A controlled social skills training for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

J Consult Clin Psychol.

2006;74(4):639-48.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

The efficacy of a child friendship training was assessed for 100 children with FASDs. The findings suggest that children with

FASDs benefit from CFT, but that these gains may not be observed in the classroom.

Paley B, O’Connor MJ.

Behavioral Interventions for Children and Adolescents With Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders.

Alcohol Research and Health.

2011;34(1).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Reviews empirically tested interventions, methodological challenges, and suggestions for future directions in research on

the treatment of FASDs.

Peadon E, Elliott EJ.

Distinguishing between attention-deficit hyperactivity and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in children: clinical guidelines.

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat.

2010;6:509-15.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Examines the relationship between ADHD and FASD and discusses treatments.

Ramsay M.

Genetic and epigenetic insights into fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

Genome Med.

2010;2(4):27.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

The severity of FASD from in utero alcohol exposure depends on many factors, and damage can occur throughout gestation. Preconception

alcohol exposure can also have a detrimental effect on the offspring.

Riley EP, Infante MA, Warren KR.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: an overview.

Neuropsychol Rev.

2011;21(2):73-80.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Discusses the evolving considerations for diagnosis of FASDs and includes a comparison of the various diagnostic schemas.

Rovasio RA, Battiato NL.

Role of early migratory neural crest cells in developmental anomalies induced by ethanol.

Int J Dev Biol.

1995;39(2):421-22.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Sanders J, Buck G.

A Long Journey: Biological and non-biological parents’ experiences raising children with FASD.

J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol.

2010;Vol 17 (2)(Summer).

/ Full Text

Santostefano, Sebastiano.

Cognitive Control Battery: Manual.

Western Psychological Services;

1988.

102-737-958 http://www.worldcat.org/title/cognitive-control-battery-ccb-manual/ocl...

A progressive skill-building method that teaches strategies for children to acquire and organize information. The goal is

for the child to understand his own learning style and learning challenges. It has shown some promising results.

Streissguth A, Kanter J ed.

The Challenge of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Overcoming Secondary Disabilities.

1st ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press;

1997.

978-0295976501 http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=UZ8WEp9Ni1QC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&...

Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Sampson PD, O'Malley K, Young JK.

Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects.

J Dev Behav Pediatr.

2004;25(4):228-38.

PubMed abstract

Clinical descriptions of patients with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) and Fetal Alcohol Effects (FAE) suggest major problems

with adaptive behavior. Five operationally defined adverse outcomes and 18 associated risk/protective factors were examined

using a Life History Interview with knowledgeable informants of 415 patients with FAS or FAE.

Wasdell MB, Jan JE, Bomben MM, Freeman RD, Rietveld WJ, Tai J, Hamilton D, Weiss MD.

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of controlled release melatonin treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome and impaired

sleep maintenance in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities.

J Pineal Res.

2008;44(1):57-64.

PubMed abstract

Watson SL, Hayes SA, Coons KD, Radford-Paz E.

Autism spectrum disorder and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Part II: a qualitative comparison of parenting stress.

J Intellect Dev Disabil.

2013;38(2):105-13.

PubMed abstract

Wattendorf DJ, Muenke M.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

Am Fam Physician.

2005;72(2):279-82, 285.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Williams JF, Smith VC.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders.

Pediatrics.

2015;136(5):e1395-406.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Focuses on the role of the medical home in prevention, intervention, and treatment of FASDs.

Get Help in Rhode Island

Get Help in Rhode Island