Hearing Screening

Screening tools and recommendations for screening children for hearing loss

Key Points

- The 1-3-6 Rule is crucial for early detection and timely intervention of hearing loss (although 1-2-3 is even better). All newborns should have their hearing screening completed by 1 month of age. A failed screen should be evaluated with a complete audiologic diagnostic evaluation by 3 months of age. If found to have hearing loss, infants should be referred to Early Intervention services as soon as possible, ideally by 6 months of age.

- Since hearing loss can be acquired or progressive, it is recommended to continue screening hearing throughout childhood and adolescence with a combination of school-based and well-child check screenings. It is also recommended that all infants and children, regardless of newborn hearing screening outcome, should have communication milestones monitored according to the periodicity tables.

- Regardless of the newborn hearing screen status, the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing recommends referral for audiologic evaluation for any child with delays in speech development or auditory skills, along with referral if there is any parental concern regarding speech or hearing.

- Risk factors associated with childhood hearing loss include NICU stay, exposure to ototoxic medications, prenatal infections, and genetic conditions. These risk factors require a follow-up diagnostic hearing test at 9 months of age. [Joint: 2019]

- Children who are found to have hearing loss necessitate a comprehensive medical evaluation. It is recommended to refer children to audiology, otolaryngology, ophthalmology, genetics, and speech-language pathology for further testing.

- Primary care providers can find pediatric audiologists in their area at Find an Audiologist (American Academy of Audiology) and Find a Hearing Facility (EHDI-PALS).

Assessment Recommendations

The American Academy of Audiology advises school-based screening in preschool, kindergarten, and grades 1, 3, 5, and either 7 or 9. [American: 2011] The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends subjective assessment of hearing (and assessment of risk for hearing loss) at all well-child examinations and objective hearing screening at school entry. When possible, the AAP also advises objective office-based screening for children 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 13, 16, and 20 years old. Given the risk of hazardous noise exposure in adolescents, it is recommended to perform audiometry screening in adolescents that includes 6,000 and 8,000 Hz high frequencies. The AAP Periodicity Schedule recommends high-frequency screening once between ages 11-14, once between ages 15-17, and again between ages 18-21.

Regardless of the newborn hearing screen status, the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing recommends referral for audiologic evaluation for any child with delays in speech development or auditory skills, along with referral if there is any parental concern regarding speech or hearing.

Developmental abnormalities, poor cognitive function, or behavioral problems (e.g., autism/developmental delay) may preclude accurate results on routine audiometric screening. Referral to a pediatric audiologist with the necessary equipment and expertise to test infants and young children should be considered. If the audiologic evaluation is concerning, referral to an otolaryngologist would be the next step.

The following algorithms provide further guidance.

- Office Visit Hearing Assessment Algorithm (AAP): One-page algorithm accounting for risk factors and screen results [Harlor: 2009]

-

Algorithm for Pediatric Medical Home Providers (AAP) (

243 KB): One-page

algorithm for screening, evaluation, and intervention of infants 0-6 months

old; from the American Academy of Pediatrics Early Hearing Detection and

Intervention (EHDI) program.

243 KB): One-page

algorithm for screening, evaluation, and intervention of infants 0-6 months

old; from the American Academy of Pediatrics Early Hearing Detection and

Intervention (EHDI) program.

Risk Factors for Hearing Loss

Risk factors that may warrant screening beyond that routinely recommended include:

- Caregiver or clinician concern regarding speech, language, or hearing delay based on surveillance or developmental screening

- Family history of permanent childhood hearing loss

- Birth weight <1500 g

- Neonatal intensive care ≥5 days (although some recommend any NICU length of stay) [Garinis: 2018]

- A history of ECMO (5-28% of ECMO survivors had hearing loss on follow-up testing) [Garinis: 2018]

- Hyperbilirubinemia requiring exchange transfusion

- Ototoxic medications >5 days, including aminoglycosides and glycopeptide antibiotics (gentamicin and tobramycin), loop diuretics (furosemide), and chemotherapy

- Mechanical ventilation >5 days

- Intrauterine TORCH infections, such as cytomegalovirus, herpes, rubella, syphilis, and toxoplasmosis

- Conditions associated with hearing loss - There are over 400 syndromes associated with hearing loss, such as neurofibromatosis type 2, osteopetrosis, and syndromes, such as Usher, Waardenburg, CHARGE, Alport, Pendred, and Jervell and Lange-Nielson.

- Neurodegenerative disorders, such as Hunter syndrome, or sensory-motor neuropathies, such as Friedreich ataxia and Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome [Harlor: 2009]

- Culture-positive postnatal infections associated with sensorineural hearing loss, including confirmed bacterial and viral (especially herpes viruses and varicella) and meningitis

- Head trauma, especially basal skull/temporal bone fracture that requires hospitalization

- Recurrent/persistent otitis media with effusion >3 months (or less if any other risk factors, such as speech delay) [Rosenfeld: 2016]

The Joint Committee also recommends that an AABR screen be performed prior to discharge (even if the newborn hearing screen was passed prior to re-admission) for newborns who are re-admitted in the first month of life for conditions that are associated with hearing loss, such as sepsis and hyperbilirubinemia requiring an exchange transfusion.

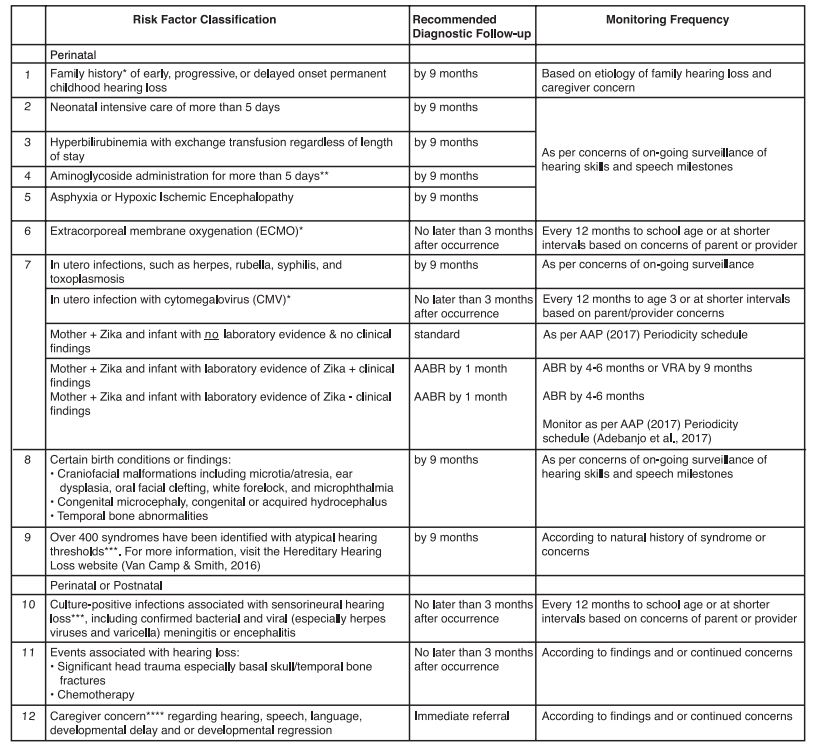

The following table from the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing’s report (2019) [Joint: 2019] provides recommendations on when to re-screen infants based on specific risk factors for hearing loss.

Risk Factors for Early Childhood Hearing Loss: Guidelines for Infants who

Pass the Newborn Hearing Screen

See Early Childhood Hearing Outreach Initiative (NCHAM) for information on screening young children with otoacoustic emissions in the office. [Liming: 2016]

Failed Hearing Screens: Next Steps

Newborns in the nursery who fail otoacoustic emission (OAE) screening can be re-screened by auditory brainstem response (AABR), if available, before discharge from the newborn nursery. If the AABR is passed, the infant has a passed newborn hearing screen and should be re-screened per guidelines detailed elsewhere in this article or as concerns arise. If the infant fails the AABR screen (either primarily or as the re-screen) or is unable to access an AABR, they may be re-screened as an outpatient prior to 1 month of age or referred for formal audiologic evaluation prior to 3 months (next steps vary from state to state).

1-3-6 Guidance for Medical Home Providers (AAP) ( 257 KB) has a helpful flowchart for next steps if the hearing screen is

not passed in the first 3 months of life. Note that infants admitted to the NICU

should only be screened by AABR or ABR modalities, given their risk of neural

hearing loss. In some states, targeted Congenital Cytomegalovirus (CMV) testing

is mandated for infants not passing their newborn hearing screening, while in

others, universal CMV testing is completed as part of the newborn metabolic

screen. Be sure to know the requirements in your state and ensure that necessary

testing has been completed. If there is no mandated CMV testing, consider if

this makes sense for your practice. Read more information at Newborn Screening (National CMV Foundation).

257 KB) has a helpful flowchart for next steps if the hearing screen is

not passed in the first 3 months of life. Note that infants admitted to the NICU

should only be screened by AABR or ABR modalities, given their risk of neural

hearing loss. In some states, targeted Congenital Cytomegalovirus (CMV) testing

is mandated for infants not passing their newborn hearing screening, while in

others, universal CMV testing is completed as part of the newborn metabolic

screen. Be sure to know the requirements in your state and ensure that necessary

testing has been completed. If there is no mandated CMV testing, consider if

this makes sense for your practice. Read more information at Newborn Screening (National CMV Foundation).

Furthermore, any child who does not pass a subsequent hearing screen should have a formal evaluation by a licensed audiologist. Children who are found to have hearing loss necessitate a comprehensive medical evaluation. [Joint: 2019] It is important to perform a thorough physical exam, looking for stigmata of genetic conditions or abnormalities of the head and neck areas, such as cleft lip or palate, heterochromia of the irises, and microcephaly, among others. Consider work-up for congenital cytomegalovirus infection and look for cardiac or renal anomalies. Primary care providers should request copies of the audiology report with the audiologist’s recommendations for further diagnostic evaluation. This report will also be sent to the state EHDI program. Once a child is determined to have hearing loss, a referral to the early intervention program is recommended within 7 days, and the JCIH recommends referral within 48 hours. [Joint: 2019]

Primary care clinicians can educate families on the connection between hearing and language development to help parents understand the importance of follow-up with appointments and early intervention services. The primary care provider should continue to monitor the child’s development and intervene as necessary.

How Hearing is Screened

Hearing screening is typically a simple evaluation providing “pass/fail” results. It is commonly performed in the newborn nursery or birthing center, primary care clinic, school, and daycare settings. People other than audiologists may be trained to provide hearing screening, including nurses, early intervention specialists, medical technicians, medical assistants, and teachers. Failed hearing screens should trigger more extensive diagnostic testing performed by a licensed (preferably pediatric) audiologist. Passing results usually do not require further hearing evaluations until the next recommended screening unless there is a strong index of suspicion or a known risk factor for late-onset hearing loss.

The most common methods used to test children’s hearing include:

- Otoacoustic emission (OAE) testing

- Auditory brainstem response (ABR) testing or brainstem auditory-evoked response (BAER)

- Pure-tone testing/audiogram

It is important for the primary care physician to remember that although OAEs and ABRs test the “structural integrity” of a child’s hearing, the behavioral pure-tone audiogram is the true measure of a child’s hearing ability. As Harlor and Bower note, “[e]ven if ABR or OAE test results are normal, hearing cannot be definitively considered normal until a child is mature enough for a reliable behavioral audiogram to be obtained. " [Harlor: 2009]

If a primary care office has screening equipment, it should be calibrated yearly. Those administering the screen should be trained appropriately. [Stewart: 2019]

Otoacoustic Emission (OAE)

Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) / Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response (BAER) Testing

40 KB). Of note, infants who

have been admitted to the NICU for >5 days should be screened by ABR. [Joint: 2019]

40 KB). Of note, infants who

have been admitted to the NICU for >5 days should be screened by ABR. [Joint: 2019]

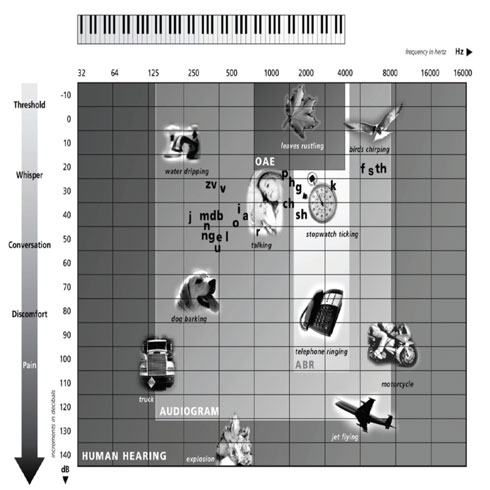

Audiometry

684 KB)).

684 KB)).

1.0 MB) (right) shows human

hearing in hertz frequencies and the range that audiograms test. The range of

hearing that the audiogram represents is shown on the chart in the shaded area

labeled “AUDIOGRAM.” Also, see an example of an Audiogram Showing Hearing Loss (

1.0 MB) (right) shows human

hearing in hertz frequencies and the range that audiograms test. The range of

hearing that the audiogram represents is shown on the chart in the shaded area

labeled “AUDIOGRAM.” Also, see an example of an Audiogram Showing Hearing Loss ( 269 KB).

269 KB).

233 KB) offers an overview of

the different audiologic tests available.

233 KB) offers an overview of

the different audiologic tests available.

Who Provides Pediatric Hearing Testing?

For failed hearing screens, diagnostic testing (“hearing evaluation”) should be performed only by a licensed audiologist trained in testing children and has access to the testing equipment needed to evaluate children. Children with special health care needs are best served by a pediatric audiologist with experience in working with this population. Early Intervention programs usually offer hearing screening or testing, as will state programs focused on children with special health care needs and/or disabilities. Newborn screening programs can also guide you to reliable resources, particularly those focused on following up on abnormal newborn screens.

Costs and Insurance Coverage

The cost of hearing testing can range from <$100 for a screening evaluation to >$700 for a full diagnostic evaluation, depending on the comprehensiveness of testing. Sedated procedures will cost more because medical staff is needed to provide safe sedation with patient monitoring. In many cases, insurance and other third-party payers will cover the cost of testing. Co-pays and deductibles will apply, so each family should check their insurance benefits to understand the cost before testing is performed. Some insurance plans will require a referral from a physician.

Normal Hearing Milestones

Normal hearing is essential for normal speech and language development in children. Even mild or fluctuating hearing loss can impact a child’s speech and language development. Though most children are now screened for hearing loss as newborns, it is important to retest hearing when there are concerns about hearing or speech/language development. Failure to meet the developmental milestones below should raise concern.

| between 0-3 months, the child: | between 3-6 months, the child: |

|---|---|

|

|

| between 6-9 months, the child: | between 9-12 months, the child: |

|---|---|

|

|

Services and Referrals

- Newborns who do not pass their hearing screen on rescreen (in either one or both ears) should be referred for a diagnostic ABR with a pediatric audiologist.

- Newborns noted to have congenital aural atresia or pinna/ear canal deformity

- Infants in the NICU who fail the AABR

- Infants or children with delays in communication and/or auditory skills regardless of newborn hearing screening results. Infants or children whose parents have concerns regarding their speech or hearing abilities.

Resources

Information & Support

Related Portal Content

- Hearing Loss & Deafness

- Congenital Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Related Hearing Loss

- Missing link with id: d90b91f.xml

- Hearing Loss and Deafness (FAQ)

- Hearing Aids

For Professionals

National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management (USU)

A national resource center for the implementation and improvement of comprehensive and effective Early Hearing Detection and

Intervention (EHDI) systems; Utah State University.

Early Childhood Hearing Outreach Initiative (NCHAM)

The ECHO initiative provides extensive information, including tutorials and resource links, to support health care providers

screening for hearing in young children; National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management.

Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (AAP)

Enhances clinical knowledge of the EHDI program and screening guidelines and helps to ensure that newborn screening results

are communicated to families and reported according to state laws. Also has links to state chapters, EHDI experts, and resources;

American Academy of Pediatrics and the Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Program.

Hearing Loss in Children – Recommendations and Guidelines (CDC)

Collection of recommendations and guidelines related to hearing screening and hearing loss in infants and children; Centers

for Disease Control.

For Parents and Patients

My Baby's Hearing (NIDCD)

Information for families about hearing screening and hearing loss, follow-up, amplification options, and more. A link to the

site in Spanish is on the home page; Boys Town National Research Hospital and the National Institute on Deafness and Other

Communication Disorders.

Hearing Loss in Children (CDC)

Information, statistics, screening/diagnosis, and treatments; from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

OAE Video (kidshearing.org)

A 1-minute video demonstrating use of OAE testing from infanthearing.org.

Learning About Hearing Loss - A Roadmap for Families (NCHAM) ( 347 KB)

347 KB)

Graphic representation of the path to learning about hearing loss, from a positive newborn hearing screen to 6 months of age;

National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management.

Practice Guidelines

Harlor AD Jr, Bower C.

Hearing assessment in infants and children: recommendations beyond neonatal screening.

Pediatrics.

2009;124(4):1252-63.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Joint Committee on Infant Hearing.

Year 2019 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs.

Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention.

2019.

/ Full Text

Liming BJ, Carter J, Cheng A, Choo D, Curotta J, Carvalho D, Germiller JA, Hone S, Kenna MA, Loundon N, Preciado D, Schilder

A, Reilly BJ, Roman S, Strychowsky J, Triglia JM, Young N, Smith RJ.

International Pediatric Otolaryngology Group (IPOG) consensus recommendations: Hearing loss in the pediatric patient.

Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.

2016;90:251-258.

PubMed abstract

Expert opinion by the members of the International Pediatric Otolaryngology Group on the workup of hearing loss in the pediatric

patient.

Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, Coggins R, Gagnon L, Hackell JM, Hoelting D, Hunter LL, Kummer AW, Payne SC, Poe DS, Veling

M, Vila PM, Walsh SA, Corrigan MD.

Clinical Practice Guideline: Otitis Media with Effusion (Update).

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

2016;154(1 Suppl):S1-S41.

PubMed abstract

Update of a 2004 guideline co-developed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, the American

Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Family Physicians, provides evidence-based recommendations to manage otitis

media with effusion (OME).

Tools

Bright Futures/AAP Periodicity Schedule

Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care; American Academy of Pediatrics.

Office Visit Hearing Assessment Algorithm (AAP)

One-page algorithm accounting for risk factors and screen results from Hearing Assessment in Infants and Children: Recommendations

Beyond Neonatal Screening

Allen D. Buz Harlor, Charles Bower; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine,

Pediatrics October 2009.

Algorithm for Pediatric Medical Home Providers (AAP) ( 243 KB)

243 KB)

One-page algorithm for screening, evaluation, and intervention of infants 0-6 months old; from the American Academy of Pediatrics

Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) program.

Guidelines for Medical Home: Reducing Loss to Follow-Up in Newborn Hearing Screening (AAP) ( 160 KB)

160 KB)

One-page algorithm for follow-up of the newborn hearing screen beginning with the first newborn pediatric patient care visit;

National Center for Medical Home Implementation, sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Services for Patients & Families in Rhode Island (RI)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | RI | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NM | NV | UT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audiology | 24 | 3 | 22 | 8 | 22 | |||

| CSHCN Administration & Programs | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 7 | |||

| Developmental - Behavioral Pediatrics | 12 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9 | |||

| Early Intervention for Children with Disabilities/Delays | 13 | 3 | 34 | 30 | 51 | |||

| Pediatric Nephrology | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Pediatric Neurology | 18 | 5 | 5 | 8 | ||||

| Pediatric Ophthalmology | 8 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 4 | |||

| Pediatric Otolaryngology (ENT) | 7 | 1 | 11 | 5 | 10 | |||

| Speech and Hearing Services | 20 | 7 | 36 | 12 | 29 | |||

| Speech - Language Pathologists | 33 | 4 | 23 | 11 | 65 | |||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Authors & Reviewers

| Author: | Anna Falconburg, MD |

| Senior Author: | Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAP |

| Reviewer: | Adrienne Johnson, Au.D. CCC-A |

| 2023: update: Anna Falconburg, MDA; Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPSA |

| 2020: update: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPA |

| 2013: update: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPCA |

| 2011: first version: Nancy Hohler, AuD, MBAA |

Page Bibliography

American Academy of Audiology.

American Academy of Audiology.

(2011)

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/documents/AAA_Childhood-Hearing....

Garinis AC, Kemph A, Tharpe AM, Weitkamp JH, McEvoy C, Steyger PS.

Monitoring neonates for ototoxicity.

Int J Audiol.

2018;57(sup4):S41-S48.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Reviews current practice and discusses the feasibility of designing improved ototoxicity screening and monitoring protocols

to better identify acquired, drug-induced hearing loss in NICU neonates

Harlor AD Jr, Bower C.

Hearing assessment in infants and children: recommendations beyond neonatal screening.

Pediatrics.

2009;124(4):1252-63.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Joint Committee on Infant Hearing.

Year 2019 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs.

Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention.

2019.

/ Full Text

Liming BJ, Carter J, Cheng A, Choo D, Curotta J, Carvalho D, Germiller JA, Hone S, Kenna MA, Loundon N, Preciado D, Schilder

A, Reilly BJ, Roman S, Strychowsky J, Triglia JM, Young N, Smith RJ.

International Pediatric Otolaryngology Group (IPOG) consensus recommendations: Hearing loss in the pediatric patient.

Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.

2016;90:251-258.

PubMed abstract

Expert opinion by the members of the International Pediatric Otolaryngology Group on the workup of hearing loss in the pediatric

patient.

Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, Coggins R, Gagnon L, Hackell JM, Hoelting D, Hunter LL, Kummer AW, Payne SC, Poe DS, Veling

M, Vila PM, Walsh SA, Corrigan MD.

Clinical Practice Guideline: Otitis Media with Effusion (Update).

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

2016;154(1 Suppl):S1-S41.

PubMed abstract

Update of a 2004 guideline co-developed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, the American

Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Family Physicians, provides evidence-based recommendations to manage otitis

media with effusion (OME).

Stewart JE, Bentley JE.

Hearing Loss in Pediatrics: What the Medical Home Needs to Know.

Pediatr Clin North Am.

2019;66(2):425-436.

PubMed abstract

Yoshinaga-Itano C, Sedey AL, Coulter DK, Mehl AL.

Language of early- and later-identified children with hearing loss.

Pediatrics.

1998;102(5):1161-71.

PubMed abstract

Get Help in Rhode Island

Get Help in Rhode Island