Fabry Disease

Overview

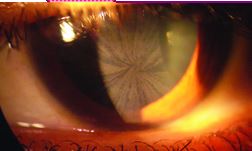

As an X-linked disorder, males with Fabry disease are typically more severely affected. Classically, males will present with signs/symptoms in early childhood. Early signs/symptoms include angiokeratomas, episodic acroparesthesia, sweating abnormalities, and corneal and lenticular opacities. This may then progress to typically adult-onset renal disease/failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and cerebrovascular disease.

Though much less common, there are milder forms of Fabry disease in which some organ systems may be affected more than others. Heterozygous females present with significantly more clinical variability ranging from the complete absence of symptoms throughout life to being as severely symptomatic as males.

The current therapeutic approach involves enzyme replacement therapy (ERT). While not a cure, ERT positively impacts pain, kidney function, and possibly other organs. [El: 2016] Patients with specific genetic variants might respond to oral chaperone therapy with migalastat. [Feldt-Rasmussen: 2020] Clinical trials are ongoing for additional therapeutic approaches.

Other Names & Coding

E75.21, Fabry (-Anderson) disease

Prevalence

Genetics

Notably, heterozygous females may not just be carriers; the majority will experience some symptoms of Fabry, though typically less severe than their male counterparts.

Due to the X-linked inheritance, women with a Fabry-associated gene variant have a 50% chance of passing the gene to their child regardless of sex, while men with the Fabry disease will pass it to all of their daughters only. In 1-2% of patients, a Fabry-associated gene mutation is de novo (i.e., not inherited from a parent). [Sestito: 2013] An individual with a de novo mutation will still pass the condition following an X-linked inheritance pattern.

Prognosis

Practice Guidelines

Ortiz A, Germain DP, Desnick RJ, Politei J, Mauer M, Burlina A, Eng C, Hopkin RJ, Laney D, Linhart A, Waldek S, Wallace E,

Weidemann F, Wilcox WR.

Fabry disease revisited: Management and treatment recommendations for adult patients.

Mol Genet Metab.

2018;123(4):416-427.

PubMed abstract

Laney DA, Bennett RL, Clarke V, Fox A, Hopkin RJ, Johnson J, O'Rourke E, Sims K, Walter G.

Fabry disease practice guidelines: recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors.

J Genet Couns.

2013;22(5):555-64.

PubMed abstract

Roles of the Medical Home

- Providing education and support

- Identifying sources of information and other needed resources

- Monitoring for disease symptoms control

- Coordinating care with subspecialists

- Advocating for needed accommodations at school/work

Clinical Assessment

Overview

258 KB).

258 KB).

Pearls & Alerts for Assessment

Genetic analysis is necessary to confirm a diagnosis in femalesFemales with Fabry disease may have normal α-galactosidase enzyme activity and LysoGL-3 levels, so a GLA genetic analysis should be used to confirm diagnosis. [Mehta: 2010]

Females who have the Fabry gene are often symptomaticDespite the X-linked inheritance pattern, approximately 70% of women are not simply "carriers" of Fabry but are also symptomatic. Females should be assessed regularly for disease progression.

Screening

For the Condition

In states without newborn screening, children with a family history of Fabry and those with corneal whorling (cornea verticillata) found on a slit lamp eye exam should be tested as these are very specific findings. [Laney: 2013] Testing may also be warranted in persons with 2 or more of the following symptoms:

- Vascular cutaneous lesions (angiokeratomas)

- Sweating abnormalities (anhidrosis, hypohidrosis, and rarely hyperhidrosis)

- Personal or family history of:

- Periodic crises of severe pain in the hands/feet (acroparesthesia)

- Unexplained renal failure

- Unexplained stroke

496 KB)

describes appropriate screening and testing for Fabry disease based on

indications and gender of the child

496 KB)

describes appropriate screening and testing for Fabry disease based on

indications and gender of the child

Of Family Members

For Complications

Presentations

The disease will eventually progress, and during adolescence/adulthood, patients may experience heart, kidney, and central nervous system problems. [Mehta: 2010] [Sestito: 2013] [Löhle: 2015] Cardiac disease may include mitral insufficiency, conduction abnormalities, left ventricular enlargement, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Renal disease typically starts with proteinuria followed by azotemia and gradual deterioration of renal function in the 3rd to 5th decade of life. Cerebrovascular disease caused by small vessel involvement may lead to transient ischemic attacks, aneurysms, seizures, and cerebral strokes resulting in permanent neurological damage. Chronic gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, and abdominal pain are common, especially in females. Pulmonary disease, hearing loss, tinnitus, and psychiatric issues, such as depression and anxiety, are also commonly observed. All relevant organ systems need to be assessed, treated, and monitored. [Eng: 2006]

Males with >1% α-galactosidase A activity tend to present on a wider spectrum ranging from “classic” phenotype to organ-specific symptoms such as adult-onset involvement of the heart or kidneys only.

Females should be assessed regularly for symptom manifestations; 70% of women exhibit symptoms and are not simply “carriers.” The symptoms can occur with greater variability than in males. Some women may remain asymptomatic and, therefore, not require treatment.

Diagnostic Criteria

- Males:

- Molecular identification of hemizygous pathogenic variant in the GLA gene

- Reduced plasma α-galactosidase enzyme activity

- Elevated plasma or urinary LysoGL-3

- Females:

- Molecular identification of heterozygous pathogenic variant in the GLA gene

Differential Diagnosis

- Fibromyalgia

- Rheumatic fever

- Multiple sclerosis

- Raynaud syndrome

Comorbid & Secondary Conditions

- Ocular: Cornea verticillata (corneal whorling), lenticular changes, subcapsular cataracts

- Cerebrovascular: Transient ischemic attack (TIA), stroke, subclinical white matter lesions

- Cardiac: Arrhythmia, left ventricular hypertrophy, myocardial infarction

- Renal: Proteinuria, azotemia, reduced GFR, end-stage renal disease

- Gastrointestinal: Abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, anorexia

- Neurological: Neuropathic pain, acroparesthesia, tinnitus, sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo

- Psychosocial: Depression, anxiety, panic attacks, ADHD

- Integumentary: Angiokeratomas, anhydrosis or hypohydrosis, telangiectasia

- Other: Priapism

History & Examination

Current & Past Medical History

Family History

- Unexplained, early deaths due to renal failure

- Cardiac disease

- Stroke

- Hypohydrosis

- Episodic burning pain in the hands and feet

- Chronic unexplained gastrointestinal disturbances

Physical Exam

Skin

HEENT/Oral

| Cornea verticillata (corneal whorling) can be found on slit-lamp eye exams in 70% of females and most males with Fabry disease. [Sestito: 2013] Lenticular changes, including subcapsular deposits (Fabry” cataracts), also can be found. Notably, neither the corneal nor lenticular changes interfere with visual acuity. Photo, right: cornea verticillata / [Burlina: 2011] |

|

Heart

Sinus bradycardia and systolic murmurs may be early signs of cardiac involvement. [Sestito: 2013] Cardiac abnormalities, such as left ventricular hypertrophy, arrhythmias, and valvular insufficiency, can occur in children and adults with Fabry disease.

Testing

Sensory Testing

- An audiologic evaluation every 2-3 years

- Slit-lamp ophthalmology exam should be performed at the time of diagnosis and then as needed.

Laboratory Testing

- Glomerular filtration rate, albuminuria/proteinuria, creatinine, BUN, cystatin C

- Enzyme replacement therapy status (GL-3, LysoGL3, antibody testing)

Imaging

- EKG and echocardiogram every 2-3 years in children and yearly for adults, unless otherwise indicated

- Cranial MRI every 2-3 years, unless otherwise indicated

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Biochemical Genetics (Metabolics) (see RI providers [3])

Pediatric Cardiology (see RI providers [17])

Pediatric Nephrology (see RI providers [10])

Pediatric Gastroenterology (see RI providers [18])

General Counseling Services (see RI providers [30])

Treatment & Management

Overview

Pearls & Alerts for Treatment & Management

Minimize pain triggersExercise, fatigue, emotional stress, or rapid temperature changes may trigger episodes of pain.

Systems

Neurology

Management of neuropathic pain consists of avoidance of triggers and over-the-counter analgesics. If still unable to control the neuropathic pain, additional medications such as gabapentin, carbamazepine, or phenytoin may be indicated.

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Pediatric Neurology (see RI providers [18])

Renal

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Pediatric Nephrology (see RI providers [10])

Cardiology

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Pediatric Cardiology (see RI providers [17])

Gastro-Intestinal & Bowel Function

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Pediatric Gastroenterology (see RI providers [18])

Skin & Appearance

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Pediatric Dermatology (see RI providers [3])

Ears/Hearing

Mental Health/Behavior

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

General Counseling Services (see RI providers [30])

Pain Management (see RI providers [1])

Ask the Specialist

I am treating a child with Fabry that complains of frequent pain. On exam, I cannot find anything that would explain these symptoms. Are they really having this much pain?

Yes. The pain in Fabry disease is real and needs to be treated. Chronic, frequent pain may need treatment with neuropathic pain medications, such as Neurontin or Carbamazepine. Episodic intense periods of pain, often called “Fabry crisis,” may need to be treated with stronger pain-relieving medications.

When should enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) begin?

There is no consensus on when to start treatment with ERT; the decisions should be discussed with a metabolic specialist. Several studies have suggested that treatment should begin before critical organ changes have occurred. [Sestito: 2013] Assessment and vigilant monitoring for early symptoms and collaboration with a metabolic geneticist are vital. Studies show ERT is less effective if started after a patient is exhibiting >1 g/day of proteinuria and/or GFR<60 ml/min.

Resources for Clinicians

Pain in Children with Special Health Care Needs clinical management information by types of pain.

On the Web

Fabry for Healthcare Professionals (Genzyme)

Diagnosis, genetics, and management information, patient education, publications, and other resources for clinicians.

Fabry Disease (GeneReviews)

Detailed information addressing clinical characteristics, diagnosis/testing, management, genetic counseling, and molecular

pathogenesis; from the University of Washington and the National Library of Medicine.

Fabry Disease (NORD)

Information for families includes synonyms, signs & symptoms, causes, affected populations, related disorders, diagnosis,

therapies (both standard and investigational), and support organizations; National Organization of Rare Disorders.

Helpful Articles

PubMed search for articles over the last 2 years about Fabry disease in children

Laney DA, Peck DS, Atherton AM, Manwaring LP, Christensen KM, Shankar SP, Grange DK, Wilcox WR, Hopkin RJ.

Fabry disease in infancy and early childhood: a systematic literature review.

Genet Med.

2015;17(5):323-30.

PubMed abstract

Sestito S, Ceravolo F, Concolino D.

Anderson-Fabry disease in children.

Curr Pharm Des.

2013;19(33):6037-45.

PubMed abstract

Thomas AS, Hughes DA.

Fabry disease.

Pediatr Endocrinol Rev.

2014;12 Suppl 1:88-101.

PubMed abstract

Toyooka K.

Fabry disease.

Handb Clin Neurol.

2013;115:629-42.

PubMed abstract

Clinical Tools

Care Processes & Protocols

Fabry Disease: Testing Algorithm (Mayo Clinic) ( 496 KB)

496 KB)

Describes appropriate screening and testing based on indications and gender.

Fabry: Response to Positive Newborn Screen (Mayo Clinic) ( 476 KB)

476 KB)

One-page algorithm for clinicians; Mayo Medical Laboratories.

Patient Education & Instructions

Fabry Disease: Guide for the Newly Diagnosed (Emory University) ( 141 KB)

141 KB)

Factsheet with information about the Fabry symptoms, treatment, tests, and resources.

Resources for Patients & Families

Information on the Web

Fabry Disease (NINDS)

Information about Fabry disease, treatment, prognosis, research, and links to other organizations; National Institute of Neurological

Disorders and Stroke.

GLA Gene (MedlinePlus)

Information for families that includes description, frequency, causes, inheritance, other names, and additional resources;

from the National Library of Medicine.

Fabry Inheritance Patterns (Genzyme)

Explains how to create a medical family tree to understand the inheritance pattern and risk of passing on Fabry disease.

Discover Fabry (Genzyme)

Diagnosis, management, resources, and support information for families affected by Fabry disease.

National & Local Support

Fabry Support & Information Group (FSIG)

Access to support groups, discussion forums, resources, and research related to Fabry disease.

National Fabry Disease Foundation

Information about Fabry disease, counseling, finding a physician, and the Charles Kleinschmidt Fabry Family Weekend Camp.

Studies/Registries

Clinical Trials in Fabry (clinicaltrials.gov)

Studies looking at better understanding, diagnosing, and treating this condition; from the National Library of Medicine.

Services for Patients & Families in Rhode Island (RI)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | RI | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NM | NV | UT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audiology | 24 | 3 | 22 | 8 | 22 | |||

| Biochemical Genetics (Metabolics) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| General Counseling Services | 30 | 1 | 10 | 213 | 298 | |||

| Genetic Testing and Counseling | 7 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 10 | |||

| Pain Management | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Pediatric Cardiology | 17 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Pediatric Dermatology | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 18 | 2 | 5 | 2 | ||||

| Pediatric Nephrology | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Pediatric Neurology | 18 | 5 | 5 | 8 | ||||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Authors & Reviewers

| Author: | Michael Angerbauer |

| Senior Author: | Brian J. Shayota, MD, MPH |

| Reviewer: | Nicola Longo, MD, Ph.D. |

| 2022: update: Michael AngerbauerA; Brian J. Shayota, MD, MPHSA |

| 2017: update: Susan Jensen, DNPA; Dawn LaneyCA |

| 2015: update: Meghan S Candee, MD, MScA |

| 2015: first version: Nicola Longo, MD, Ph.D.R |

Bibliography

Arends M, Hollak CE, Biegstraaten M.

Quality of life in patients with Fabry disease: a systematic review of the literature.

Orphanet J Rare Dis.

2015;10(1):77.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Burlina AP, Sims KB, Politei JM, Bennett GJ, Baron R, Sommer C, Møller AT, Hilz MJ.

Early diagnosis of peripheral nervous system involvement in Fabry disease and treatment of neuropathic pain: the report of

an expert panel.

BMC Neurol.

2011;11:61.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

El Dib R, Gomaa H, Carvalho RP, Camargo SE, Bazan R, Barretti P, Barreto FC.

Enzyme replacement therapy for Anderson-Fabry disease.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2016;7:CD006663.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Eng CM, Germain DP, Banikazemi M, Warnock DG, Wanner C, Hopkin RJ, Bultas J, Lee P, Sims K, Brodie SE, Pastores GM, Strotmann

JM, Wilcox WR.

Fabry disease: guidelines for the evaluation and management of multi-organ system involvement.

Genet Med.

2006;8(9):539-48.

PubMed abstract

An international panel of physicians with expertise in Fabry disease has proposed guidelines for the recognition, evaluation,

and surveillance of disease-associated morbidities, as well as therapeutic strategies.

Feldt-Rasmussen U, Hughes D, Sunder-Plassmann G, Shankar S, Nedd K, Olivotto I, Ortiz D, Ohashi T, Hamazaki T, Skuban N, Yu

J, Barth JA, Nicholls K.

Long-term efficacy and safety of migalastat treatment in Fabry disease: 30-month results from the open-label extension of

the randomized, phase 3 ATTRACT study.

Mol Genet Metab.

2020;131(1-2):219-228.

PubMed abstract

Gal A, Schäfer E, Rohard I.

The genetic basis of Fabry disease.

Oxford PharmaGenesis.

2006.

PubMed abstract

Chapter 33. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11574/

Germain DP.

Fabry disease.

Orphanet J Rare Dis.

2010;5:30.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Germain DP, Charrow J, Desnick RJ, Guffon N, Kempf J, Lachmann RH, Lemay R, Linthorst GE, Packman S, Scott CR, Waldek S, Warnock

DG, Weinreb NJ, Wilcox WR.

Ten-year outcome of enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase beta in patients with Fabry disease.

J Med Genet.

2015;52(5):353-8.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Hopkins PV, Klug T, Vermette L, Raburn-Miller J, Kiesling J, Rogers S.

Incidence of 4 Lysosomal Storage Disorders From 4 Years of Newborn Screening.

JAMA Pediatr.

2018;172(7):696-697.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Hsu TR, Niu DM.

Fabry disease: Review and experience during newborn screening.

Trends Cardiovasc Med.

2018;28(4):274-281.

PubMed abstract

Kaminsky P, Noel E, Jaussaud R, Leguy-Seguin V, Hachulla E, Zenone T, Lavigne C, Marie I, Maillot F, Masseau A, Serratrice

C, Lidove O.

Multidimensional analysis of clinical symptoms in patients with Fabry's disease.

Int J Clin Pract.

2013;67(2):120-7.

PubMed abstract

Laney DA, Bennett RL, Clarke V, Fox A, Hopkin RJ, Johnson J, O'Rourke E, Sims K, Walter G.

Fabry disease practice guidelines: recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors.

J Genet Couns.

2013;22(5):555-64.

PubMed abstract

Laney DA, Peck DS, Atherton AM, Manwaring LP, Christensen KM, Shankar SP, Grange DK, Wilcox WR, Hopkin RJ.

Fabry disease in infancy and early childhood: a systematic literature review.

Genet Med.

2015;17(5):323-30.

PubMed abstract

Löhle M, Hughes D, Milligan A, Richfield L, Reichmann H, Mehta A, Schapira AH.

Clinical prodromes of neurodegeneration in Anderson-Fabry disease.

Neurology.

2015;84(14):1454-64.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Mehta A, Beck M, Eyskens F, Feliciani C, Kantola I, Ramaswami U, Rolfs A, Rivera A, Waldek S, Germain DP.

Fabry disease: a review of current management strategies.

QJM.

2010;103(9):641-59.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Najafian B, Mauer M, Hopkin RJ, Svarstad E.

Renal complications of Fabry disease in children.

Pediatr Nephrol.

2013;28(5):679-87.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

National Library of Medicine.

Fabry Disease.

MedlinePlus Genetics; (2022)

https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/fabry-disease/#frequency. Accessed on July 2022.

Orteu CH, Jansen T, Lidove O, Jaussaud R, Hughes DA, Pintos-Morell G, Ramaswami U, Parini R, Sunder-Plassman G, Beck M, Mehta

AB.

Fabry disease and the skin: data from FOS, the Fabry outcome survey.

Br J Dermatol.

2007;157(2):331-7.

PubMed abstract

Ortiz A, Germain DP, Desnick RJ, Politei J, Mauer M, Burlina A, Eng C, Hopkin RJ, Laney D, Linhart A, Waldek S, Wallace E,

Weidemann F, Wilcox WR.

Fabry disease revisited: Management and treatment recommendations for adult patients.

Mol Genet Metab.

2018;123(4):416-427.

PubMed abstract

Pinto LL, Vieira TA, Giugliani R, Schwartz IV.

Expression of the disease on female carriers of X-linked lysosomal disorders: a brief review.

Orphanet J Rare Dis.

2010;5:14.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Sestito S, Ceravolo F, Concolino D.

Anderson-Fabry disease in children.

Curr Pharm Des.

2013;19(33):6037-45.

PubMed abstract

Sigmundsdottir L, Tchan MC, Knopman AA, Menzies GC, Batchelor J, Sillence DO.

Cognitive and psychological functioning in Fabry disease.

Arch Clin Neuropsychol.

2014;29(7):642-50.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Smid BE, van der Tol L, Cecchi F, Elliott PM, Hughes DA, Linthorst GE, Timmermans J, Weidemann F, West ML, Biegstraaten M,

Lekanne Deprez RH, Florquin S, Postema PG, Tomberli B, van der Wal AC, van den Bergh Weerman MA, Hollak CE.

Uncertain diagnosis of Fabry disease: consensus recommendation on diagnosis in adults with left ventricular hypertrophy and

genetic variants of unknown significance.

Int J Cardiol.

2014;177(2):400-8.

PubMed abstract

Spada M, Pagliardini S, Yasuda M, Tukel T, Thiagarajan G, Sakuraba H, Ponzone A, Desnick RJ.

High incidence of later-onset Fabry disease revealed by newborn screening.

Am J Hum Genet.

2006;79(1):31-40.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Tahir H, Jackson LL, Warnock DG.

Antiproteinuric therapy and fabry nephropathy: sustained reduction of proteinuria in patients receiving enzyme replacement

therapy with agalsidase-beta.

J Am Soc Nephrol.

2007;18(9):2609-17.

PubMed abstract

Thomas AS, Hughes DA.

Fabry disease.

Pediatr Endocrinol Rev.

2014;12 Suppl 1:88-101.

PubMed abstract

Toyooka K.

Fabry disease.

Handb Clin Neurol.

2013;115:629-42.

PubMed abstract

Waldek S, Patel MR, Banikazemi M, Lemay R, Lee P.

Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with Fabry disease: findings from the Fabry Registry.

Genet Med.

2009;11(11):790-6.

PubMed abstract

Get Help in Rhode Island

Get Help in Rhode Island