Anxiety Disorders

Guidance for primary care clinicians diagnosing and managing children with anxiety disorders

Anxiety is defined as "anticipation of future threat." [American: 2022] Children with anxiety disorders tend to be worriers and can seem irritable or easily embarrassed.

Other Names

| Agoraphobia | Selective mutism |

| Anxiety disorder due to another medical condition | Separation anxiety disorder |

| Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) | Social anxiety disorder (social phobia) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) | Specific phobia |

| Other specified anxiety disorder | Substance/medication-induced anxiety disorder |

| Panic disorder | Unspecified anxiety disorder |

| Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) |

Key Points

Most common pediatric anxiety disorders

Anxiety often has its onset during childhood. The “pediatric triad

of anxiety disorders” includes generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety

disorder, and separation anxiety disorder. These disorders affect similar areas

of the brain, can frequently co-occur, and tend to respond similarly to

medication and behavioral interventions. [Wehry: 2015] The most common anxiety

disorders in younger children are separation anxiety and specific phobias. The

most common anxiety disorder in adolescents is social phobia. [Bagnell: 2011]

Seek information from other caregivers

Obtaining

supplementary information from other caregivers, teachers, counselors, and

others who regularly interact with the child can be extremely helpful in

establishing the diagnosis and a treatment plan.

Identify specific stressors

Taking a careful history and

delineation of the primary source of anxiety are necessary for appropriate

diagnosis and treatment. If anxiety occurs predominantly in a particular

situation or setting, such as school, more intensive interventions may be

focused on those settings. If post-traumatic stress disorder is suspected and

abuse, neglect, or safety concerns arise that have not been previously reported

or investigated, adherence to mandated reporter laws in the clinician’s area of

practice is imperative.

Evaluation and treatment of underlying medical

concerns

Sometimes, symptoms of anxiety, irritability, or

behavioral changes are due to an underlying medical concern rather than an

anxiety disorder. This should particularly be considered in CYSHCN with limited

verbal or communication abilities. Conversely, some anxiety disorders present,

often in younger children, with prominent somatic symptoms, such as headaches,

stomachaches, or sleep disturbance, with no apparent medical cause or symptoms

that are out of proportion to what would be expected for a preexisting medical

condition.

Therapy alone vs. combination therapy

Cognitive behavioral

therapy (CBT) and other therapy modalities are effective in treating anxiety

disorders and can have long-lasting effects. Therapy alone is low-risk,

well-tolerated, and often effective for mild to moderate anxiety. For patients

with moderate to severe anxiety, there is evidence that combination treatment is

superior to therapy or medication alone both in acute phase treatment and for

longer-term benefit. [Wang: 2017]

[Piacentini: 2014]

[Walkup: 2008]

SSRI dosing may be higher for anxiety than for

depression

Treatment of anxiety with SSRIs may require higher

doses than treatment for depression does. Starting doses are the same, although,

for individuals with significant worry about side effects, a lower dose may be

chosen. For CYSHCN, lower doses and slow titration of medications are

recommended due to a higher risk of side effects.

A medication trial must be of adequate dose and

duration

Treatment duration is as important as optimal dosing.

A medication should be tried for at least 4-6 weeks at an adequate dosage before

considering it a failure. Therapy is a useful adjunct to medication during this

time and can help the individual learn other coping mechanisms for managing

anxiety.

Short-acting benzodiazepines are not recommended

Short-acting

benzodiazepines should only be considered for severe anxiety (i.e., complete

refusal of life activities and inability to function as a result of anxiety) and

with supervision by a psychiatrist. Longer-acting formulations are preferred,

and a plan to taper should be developed at initiation.

Behavioral interventions for sleep anxiety

For anxiety about

going to sleep, behavioral interventions can be very helpful (see Behavioral Techniques to Improve Sleep). For example, gradually

moving a child’s sleep location from the parents’ bed to the floor and

eventually to the child’s bed, or systematically checking/reassuring the child

with timed intervals (5, 10, 15 minutes), and coupling these with positive

rewards can help many children.

Alternative medication use

Many people use “natural” medicine

to manage anxiety symptoms. Ask about all over-the-counter medications, herbs,

supplements, and other treatments that have been tried or are being tried. Using

large doses of anything can lead to side effects and toxicity. Product quality

varies among manufacturers. Herbs and Dietary Supplements Program (OSU) is an online

training program for clinicians that categorizes various natural approaches to

treating anxiety based on evidence and risks. Integrative Medicine for CYSHCN

discusses often used alternative therapies.

Treating anxiety in children with autism spectrum

disorder

According to a 2016 review of psychoactive medications

used to treat anxiety and depression in children with autism, response to

medications may differ from responses in neurotypical youth. There is reasonable

evidence suggesting better control of anxiety symptoms with use of

extended-release guanfacine (Intuniv), atomoxetine (Strattera), and buspirone

(BuSpar). SSRI use (citalopram, sertraline, fluoxetine) remains the first-line

medical treatment, but there is limited evidence for SSRI use in treating

anxiety in children with ASD and increased risk of activation. Children with

“high-functioning” ASD often can benefit from CBT.

Treating anxiety in children with ADHD

It is often

recommended to treat anxiety first, but because uncontrolled ADHD symptoms can

exacerbate anxiety (such as worrying about inadequate performance in the

classroom setting) and because stimulant trials are faster than SSRI trials,

some practitioners may choose to treat the ADHD symptoms first. Careful clinical

questioning regarding the primary source of distress and use of screening

questionnaires can help determine which to treat first. If a patient appears

more anxious or agitated on stimulant medication, consideration should be made

to treat anxiety first. Clonidine, guanfacine, and atomoxetine mayhelp some

symptoms of both anxiety and ADHD. See Anxiety Disorders & Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) for more information.

When does worry become an anxiety disorder after a stressful life

event?

Many children experience temporary and transient worry

after life changes, such as moves or transitions. Adjustment disorder can be

considered for children who experience mood or anxiety symptoms after a

stressor, and these generally resolve within 6 months after removal of the

stressor. The DSM-5clearly outlines the times for which symptoms must

persist in order to meet criteria for anxiety disorder (for most anxiety

disorders, symptoms must be present for at least 6 months, although there are

some exceptions). If a child is not experiencing significant disruptions in

functioning (academic, social, or otherwise), then they may not meet severity

criteria for a disorder. Medications may not be warranted in this case, but

brief therapy may be helpful to aid in the transition.

Re-evaluation

Periodic re-evaluation to assess for the

presence of one or more anxiety disorders is reasonable since they can occur at

any age and may change over time.

Practice Guidelines

Walter HJ, Bukstein OG, Abright AR, Keable H, Ramtekkar U, Ripperger-Suhler J, Rockhill C.

Clinical practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2020;59(10):1107-1124.

PubMed abstract

Connolly SD, Bernstein GA.

Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2007;46(2):267-83.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Geller D, March J.

Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2012;51(1):98-113.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Cohen JA, Bukstein O, Walter H, Benson SR, Chrisman A, Farchione TR, Hamilton J, Keable H, Kinlan J, Schoettle U, Siegel M,

Stock S, Medicus J.

Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2010;49(4):414-30.

PubMed abstract

Diagnosis

- Prior mental health disorders and response to past treatments

- Chronic or past acute medical conditions, noting those that can co-occur or result in anxiety

- Prior hospitalizations, surgeries, and other medical tests and interventions that may have provoked anxiety

- Medication history - Prescription drugs with side effects that may mimic anxiety include antiasthmatics, sympathomimetics/psychostimulants, steroids, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antipsychotics (akathisia), pimozide (neuroleptic-induced SAD), and atypical antipsychotics. Nonprescription drugs with side effects that may mimic anxiety include diet pills, antihistamines, and cold medicines. [Connolly: 2007]

Presentations

- Separation anxiety in preschool/early school-age

- Specific phobias in school-age

- Social anxiety in later school-age and early adolescents

- Generalized anxiety, panic, and agoraphobia-later adolescent/young adulthood

Diagnostic Criteria and Classifications

Screening & Diagnostic Testing

115 KB) - child (45 questions) and parent (39 questions)

versions for ages 8-15, plus a preschool version filled out by parent (34 items)

or teacher (22 items). The screen scores for overall anxiety disorder, as well

as separation anxiety, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive problems,

panic/agoraphobia, generalized anxiety/overanxious, and symptoms and fears of

physical injury. T-scores >60 correlate with increased risk for an anxiety

disorder, excluding the teacher-completed preschool scale that is for

informational purposes and does not have normative data available. Based on

DSM-IV, with free access to downloadable PDFs and online scoring versions.

Available in many languages.

115 KB) - child (45 questions) and parent (39 questions)

versions for ages 8-15, plus a preschool version filled out by parent (34 items)

or teacher (22 items). The screen scores for overall anxiety disorder, as well

as separation anxiety, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive problems,

panic/agoraphobia, generalized anxiety/overanxious, and symptoms and fears of

physical injury. T-scores >60 correlate with increased risk for an anxiety

disorder, excluding the teacher-completed preschool scale that is for

informational purposes and does not have normative data available. Based on

DSM-IV, with free access to downloadable PDFs and online scoring versions.

Available in many languages.

50 KB)- assesses presence

and severity of obsessions and compulsions for both diagnosis of OCD and

monitoring treatment response in children ages 6-17. Completed by a clinician or

trained interviewer during a semi-structured interview with a child and/or

parent, instructions and tips for how to ask questions and grade responses are

included; free download. This is a more time-consuming scale that may be

challenging to use in a primary care setting. Scroll past the Y-BOCS (adult

version) to reach the CY-BOCS.

50 KB)- assesses presence

and severity of obsessions and compulsions for both diagnosis of OCD and

monitoring treatment response in children ages 6-17. Completed by a clinician or

trained interviewer during a semi-structured interview with a child and/or

parent, instructions and tips for how to ask questions and grade responses are

included; free download. This is a more time-consuming scale that may be

challenging to use in a primary care setting. Scroll past the Y-BOCS (adult

version) to reach the CY-BOCS.

Genetics & Inheritance

Prevalence

Differential Diagnosis

Co-occurring Conditions

Medical Conditions Causing Anxiety Disorders

Prognosis

Anxiety disorders in childhood are often seen prior to the onset of other psychiatric disorders such as disruptive behavior disorders and depression, which have their onset in later childhood. Although anxiety disorders often persist into adulthood, they usually have a waxing and waning course with varying degrees of symptom severity among episodes. [Beesdo: 2009] Younger children tend to have recurrent episodes of 1 anxiety disorder type, but the risk of developing multiple anxiety disorders increases with age. Anxiety disorders may contribute to development of depression and substance use disorders. [Beesdo: 2009] While many suicide prevention efforts focus on identifying youth with depression, youth affected by anxiety are also at increased risk of suicide attempts. [Wehry: 2015] Unrecognized and undertreated anxiety disorders can also lead to poorer health and educational outcomes, as well as financial and interpersonal difficulties. [Wehry: 2015]

Many people with anxiety disorders respond favorably to treatment with medication and/or therapy, and treatment effects can last beyond the acute treatment phase. [Piacentini: 2014] Only about 1/3 of patients with anxiety disorders improve without treatment; up to 1/3 of patients may have a chronic, treatment-resistant course despite intensive treatment, especially if anxiety symptoms are severe or are accompanied by a major depressive disorder. [Durham: 2012]

Treatment & Management

Most pediatric anxiety disorders can be managed in the primary care setting, ideally in collaboration with behavioral health specialists for ongoing therapy and in consultation with child psychiatrists for diagnostic dilemmas or patients that are difficult to treat conventionally. Monitoring the impact of the anxiety disorder and response to treatment is vital including both reduction of anxiety symptoms a well as improving functional impairment

For children with mild symptoms of anxiety associated with minimal impairment, treatment should be focused on lifestyle modification and evidence-based psychotherapy. For severe symptoms of limited response to therapy, combination of medication and psychotherapy are recommended. [Walter: 2020]

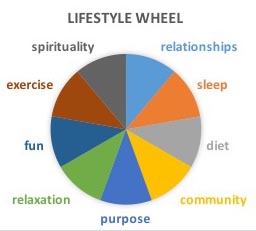

A healthy lifestyle helps anxiety. This includes regular exercise, healthy foods, adequate sleep, meaningful relationships, community engagement, stress management and relaxation practices, a sense of purpose, fun, and spirituality. [Kathi: 2010] When treating a child for anxiety, focusing on each of these components can augment, or even in some cases, take the place of treatment with prescription medications and therapy.

Mental Health / Behavior

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most empirically-supported psychotherapy based on randomized controlled studies for anxiety disorders in children that has shown both short-term and long-term efficacy. It is helpful to explain to families that CBT helps children learn to recognize and gain better control over their anxiety. CBT can be similarly effective in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder who experience anxiety. [Earle: 2016] The CBT process uses several components, such as psychoeducation, training to better manage one’s somatic complaints, cognitive restructuring (such as rethinking negative self-talk), exposure methods (i.e., gradually getting used to an anxiety-provoking situation), and plans to prevent and manage relapses. [Connolly: 2007] CBT therapists may use workbooks for kids and parents; some families defer therapy and simply use CBT-based workbooks, such as What to Do When You Worry Too Much at home. Mindfulness-based CBT is an emerging approach that may be beneficial. [Connolly: 2007] For more in-depth information and reviews of the evidence behind CBT used for different types of pediatric anxiety, see [Connolly: 2007].

Psychodynamic psychotherapy has been used extensively, though there is less high-quality evidence supporting its effectiveness. [Connolly: 2007] This approach aims to help the patient uncover and explore unconscious thoughts that contribute to their anxiety. Parents are routinely involved in both forms of therapy to help improve parent-child relationships and teach parents more effective skills to manage their child’s anxiety and support their therapeutic process.

Mental health, mindfulness, biofeedback, and meditation apps and games have proliferated. Clinicians and patients often consider these apps for convenience and privacy, and because it seems likely that most kids would prefer to play a game than go to therapy. However, “there is insufficient evidence to suggest that any mobile app for mental health can be used effectively with children and young people. Clinicians should be cautious about recommending mobile apps until there is sufficient evidence to support their safety and efficacy.” [Grist: 2017] Consider assessing children with anxiety for substance use with appropriate toxicology tests, particularly if their symptoms have sudden/episodic onset or if there are accompanying concerns on physical examination, such as mental status or autonomic changes.

Medications

402 KB) with

permission from the author, Travis Mickelson:

402 KB) with

permission from the author, Travis Mickelson:

- Fluoxetine: Start 5-10 mg daily and increase every 2-4 weeks as tolerated, up to 60 mg daily.

- Sertraline: Start 12.5-25 mg daily and increase every 2-4 weeks as tolerated, up to 200 mg daily [Earle: 2016]

- Antihistamines: They can be useful for as-needed treatment of anxiety, but the effectiveness tends to wear off with long-term use. They can cause significant sedation and other side effects, as well as decrease anxiety. They also can lower seizure threshold and interact with other medications. Examples of antihistamines include hydroxyzine (Vistaril) and diphenhydramine (Benadryl).

- Anticonvulsants: Gabapentin (Neurontin) is used to treat certain seizure disorders and neuropathic pain, but is sometimes used for anxiety. Pregabalin (Lyrica), an anticonvulsant GABA-derivative, is better studied, but it is expensive. It is approved for use in adults with generalized anxiety disorder, but not for children.

- Antihypertensives: Clonidine (e.g., Kapvay, Catapres) and guanfacine (e.g., Intuniv, Tenex) are alpha-agonists used for second-line treatment of ADHD and have some anxiolytic properties. This may be a good option for someone with ADHD and anxiety who experiences worsening anxiety on a stimulant.

- Atypical anti-anxiety medications: Buspirone (Buspar) is an anxiolytic 5-HT1A agonist that takes 1-4 weeks for onset of action and is approved for generalized anxiety disorder in adults. It is not currently FDA-approved for use in children. It does not cause dependency. There is a study with positive evidence for buspirone to treat comorbid anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder. [Earle: 2016]

- Atypical antipsychotics: They are used occasionally for severe anxiety and aggressive behaviors; however, there is significant risk of side effects, including weight gain, metabolic syndrome, movement disorders, and akathisia (a restless sensation that may mimic or worsen anxiety).

- Benzodiazepines: Little evidence exists for use in pediatric anxiety disorders. [Connolly: 2007] Procedural anxiety may be treated with lorazepam (Ativan) or diazepam (Valium), although there is some reported risk of behavioral disinhibition in young children. [Nutter: 2016] They are best used short term, but can be used to bridge the starting of SSRI therapy in youth with panic disorder. Clonazepam (Klonopin) is preferred in certain cases due to longer half-life and decreased risk of rebound anxiety. Benzodiazepines are generally avoided due to risk of abuse and diversion, and they cause significant sedation. [Nutter: 2016] Of note, children with seizures often have a benzodiazepine reserved for management of status epilepticus; regular use for treatment of anxiety may result in increased tolerance to the medication.

- Beta blockers: Propranolol has been used in adults for as-needed management of performance anxiety. [Fourneret: 2001] It also has been used to decrease aggressive behaviors and nervousness in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. [Dulcan: 2015] Little research has been done on beta blockers for pediatric anxiety; however, there is a positive case review of propranolol use for school avoidance. [Kung: 2012]

- Prazosin: This is an alpha-1 antagonist that may be useful for treatment of nightmares associate with posttraumatic stress disorder. [Kung: 2012]

- Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor: Medications, such as atomoxetine (Strattera), that are approved for treatment of ADHD have some evidence in decreasing anxiety as well and may be considered in someone with comorbid anxiety and ADHD. [León-Barriera: 2023]

- Tetracyclic antidepressants: Tetracyclic antidepressants, such as mirtazapine (Remeron), can be very sedating, so should be dosed at night. Sedative effects tend to decrease with increased doses. They can be useful in treating comorbid depression and insomnia. There is some evidence for use in treating comorbid anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder. [Earle: 2016]

- Tricyclic antidepressants: These have significant side effects, can lower seizure threshold, and increase risk of morbidity or mortality with overdose. Due to increased side effect profile these are commonly reserved for those who have failed several other medical classes. Examples include clomipramine, imipramine, amitriptyline. Clomipramine is FDA-approved for treatment of OCD; imipramine can be useful for treatment of enuresis. There is inconclusive evidence for use in separation anxiety disorders.

Learning, Education, Schools

Cardiology

Endocrine

Neurology

Social and Family Functioning

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Assess and encourage healthy lifestyle habits, including healthy diet, sleep, mind-body practices, and regular exercise.

- Be sure to ask about all over-the-counter medications, herbs,

supplements, and other treatments that have been previously tried or are

being tried. Many herbal remedies and supplements can have significant

drug-drug interactions and are not as closely monitored by the FDA as

medications. Using large doses of anything can lead to side effects and

toxicity, and product quality varies among manufacturers. Some commonly

used herbs for anxiety are listed below; however, evidence is limited,

there are potential risks associated with each, and little research on

long-term use and risks of these herbs.

- Chamomile – risk of medication interactions and allergic reactions

- Kava – risk of serious liver damage

- Lavender – risk of side effects and medication interactions

- Lemon balm – risk of side effects

- Passionflower – often combined with other products and can cause dizziness and drowsiness

- Valerian – risk of side effects, lacks long-term safety data

- Cannabidiol (CBD) has been the focus of increasing attention for use in treating almost every disorder under the sun, but little evidence exists currently on the efficacy and safety of its use for treatment of pediatric anxiety. Counsel families about the lack of quality data and regulation of over-the-counter CBD products to treat pediatric anxiety, and that these products can contain other psychoactive chemicals such as tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) which could potentially exacerbate anxiety. See CBD for Neurologic Conditions in Children for more information on pediatric medical use of CBD.

Nutrition/Growth/Bone

- Multivitamins/minerals are usually well-tolerated and can help reduce anxiety and stress in some people.

- B vitamins can help with stress; however, they may have side effects. Inositol supplements (B8) are generally safe and can be helpful for anxiety and stress.

- Vitamin C reduces feelings of stress.

- Suboptimal levels of Vitamin D are linked to anxiety in some patients with fibromyalgia.

- Calcium with magnesium and zinc can reduce anxiety.

- Low levels of magnesium are linked to anxiety. Watch for diarrhea when supplementing magnesium.

- Iodine deficiencies can result in hypothyroidism, which can be associated with anxiety.

- Iron deficiencies can result in increased feelings of stress and fatigue.

- Selenium deficiencies can result in abnormal thyroid function, and correcting deficiencies can improve anxiety in some people.

- Omega-3 fatty acids can be helpful for patients with anxiety.

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an amino acid, has unclear evidence on use in anxiety.

- D-cycloserine (DCS), an amino acid, has unclear evidence on use in anxiety.

- Theanine is an amino acid in green tea. Decaffeinated green tea could be helpful in reducing stress and promoting calm sensations.

- Tryptophan and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) are amino acids thought to help with panic and anxiety, but they can interfere with SSRIs and cause a variety of side effects.

- Deficiencies in lysine, an amino acid, are associated with increased anxiety.

- Arginine, an amino acid, can reduce anxiety and stress; however, it has potential for significant side effects.

Services & Referrals

General Counseling Services

(see RI providers

[30])

I Refer for additional testing to elucidate a diagnosis or tease

out comorbid learning or cognitive disorders. Some psychologists work as

therapists. School psychologists may assist in school support plans and

accommodations for children whose anxiety negatively impacts their ability to

effectively participate in the educational process. Refer if therapy is needed

or if help navigating social systems and coordinating services would benefit the

family.

All therapists/counselors likely have expertise/experience in managing anxiety disorders.

Psychiatry/Medication Management

(see RI providers

[80])

Refer for assistance in diagnosis and treatment of complicated

(multiple comorbidities), refractory (generally defined as more than 2

ineffective adequate antidepressant medication trials or worsening of symptoms

despite treatment), or severe cases. May provide brief consultation or routine

follow-up, depending on the needs and preferences of the primary care clinician

and family. The patient may see a nurse practitioner or physician assistant who

is supervised by a physician. Frequency of visits is usually a few times per

year.

Therapy/Counseling > …

(see RI providers

[141])

Social workers can help families identify family issues and

improve communication skills and relationships. Social workers can help with

crisis intervention and utilizing resources.

ICD-10 and DSM-5 Coding

F06.4, Anxiety disorder due to a known physiologic condition

F40.0, Agoraphobia

F40.1, Social phobia

F40.2xx, Specific phobias

F41.x, Panic disorder

F41.1, Generalized anxiety disorder

F41.9, Unspecified anxiety disorder

F42.x, Obsessive-compulsive disorder

F43.1x, Post-traumatic stress disorder

F93.0, Separation anxiety disorder of childhood

F94.0, Selective mutism

The presence of “x” indicates that further modifiers are required. For example, F42 is not a billable code; it has 5 additional modifying codes:

- F42.2, Mixed obsessional thoughts and acts

- F42.3, Hoarding disorder

- F42.4, Excoriation (skin-picking) disorder

- F42.8, Other obsessive-compulsive disorder

- F42.9, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, unspecified

Also, see ICD-10 Coding for Mental & Behavioral Disorders Due to Psychoactive Substance Use (icd10data.com) for a detailed list of codes by substance and ICD-10 Coding for Phobic Anxiety Disorders (icd10data.com) for additional codes based on specific phobic stimuli.

DSM-5 Coding

The DSM-5 billable code for GAD is 300.02 (F41. 1).

Coding for Developmental & Mental Health Screening has further coding options.

Resources

Information & Support

Related Portal Content

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Anxiety Disorders

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) & Mood Disorders

- Mental Health Screening for Children & Teens

- Postpartum Depression Screening

- Screening for Eating Disorders

- Anxiety Disorders & Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Apps to Help Kids and Teens with Anxiety

- Procedural Anxiety

- Depression (FAQ)

- Anxiety Disorders (FAQ)

Medical information in one place with fillable templates to help both families and providers. Choose only the pages needed to keep track of the current health care summary, care team, care plan, and health coverage.

For Professionals

Mental Health, Naturally

Holistic health expert and pediatrician Dr. Kathi J. Kemper presents natural treatments used for mental health issues such

as ADHD, depression, anxiety, stress, and substance abuse; available for purchase on American Academy of Pediatrics website.

Dietary Supplements (NIH)

Fact sheets for health professional and consumer that give a current overview of dietary supplements: National Institutes

of Health.

First-Line Management of Pediatric Mental Health Problems (AAP)

Free webinar about the primary care management of mental health problems in the pediatric population (49:13 minutes- July

2011) ; by Jane Meschan Foy, MD, FAAP / American Academy of Pediatrics.

Tools

Pediatric Anxiety Flowchart (UACAP) ( 402 KB)

402 KB)

One-page algorithm for assessment and treatment of pediatric anxiety; created by Dr. Travis Mickelson/Utah Academy of Child

& Adolescent Psychiatry (based on DSM-IV).

Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) (University of Pittsburgh)

A child (ages 8-18) and parent self-report with 41 questions paralleling the DSM-IV classification of anxiety disorders, including

general anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social and school phobia. Free to download, or

link to on-line Excel worksheet that calculates the score. Translations in Arabic, Chinese, French, German, Italian, Spanish,

Tamil (Sri Lanka), and Thai.

Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) ( 442 KB)

442 KB)

Assesses presence and severity of obsessions and compulsions for both diagnosis of OCD and monitoring treatment response in

children ages 6-17. Completed by a clinician or trained interviewer. Instructions and tips for how to ask questions and grade

responses are included in the screening materials link.

Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) ( 115 KB)

115 KB)

Child (45-question) and parent (39-question) forms for school-aged children. Scores for overall anxiety disorder plus scores

for separation anxiety, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive problems, panic/agoraphobia, generalized anxiety/overanxious symptoms,

and fears of physical injury. Based on DSM-IV, with free access to downloadable PDFs and online scoring versions. Available

in many languages.

Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) and Youth Report (Y-PSC) ( 47 KB)

47 KB)

Psychosocial screen to facilitate the recognition of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral problems. Includes a 35-item checklist

for parents or youth to complete, and scoring instructions. No fee required.

Online Assessment Measures (APA)

Assessments are administered at the initial patient interview and to monitor treatment progress. Instructions, scoring information,

and interpretation guidelines are included - no fee required; American Psychiatric Association.

Youth Outcome Questionnaire (OQ Measures)

A 64-item report completed by the parent/guardian. It is a measure of treatment progress for children and adolescents (ages

4-17) receiving mental health intervention. It is designed to track the patient’s sense of well-being over time in order

to gauge response to mental health interventions; available for purchase.

DSM-5 Handbook of Differential Diagnosis (APA)

A workbook with differential diagnosis pathways and decision trees that are practical for clinical use; for purchase from

the American Psychiatric Association.

Bright Futures in Practice: Mental Health—Volume II, Tool Kit

Comprehensive set of tools for clinicians and families; addresses mental health in various pediatric age groups; includes

a variety of resources, checklists, intake and assessment forms, and patient education materials.

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) Screeners

Free screening tools in many languages with scoring instructions to be used by clinicians to help detect mental health disorders.

Select from right menu: PHQ, PHQ-9, GAD-7, PHQ-15, PHQ-SADS, Brief PHQ, PHQ-4, PHQ-8.

Addressing Mental Health Concerns in Primary Care: A Clinician’s Toolkit (AAP)

Toolkit for pediatric care providers delivering comprehensive mental health care. Now in a new online format; available for

a fee from American Academy of Pediatrics.

Services for Patients & Families in Rhode Island (RI)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | RI | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NM | NV | UT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Counseling Services | 30 | 1 | 10 | 213 | 298 | |||

| Psychiatry/Medication Management | 80 | 3 | 37 | 53 | ||||

| Therapy/Counseling | 141 | 25 | 90 | 357 | 586 | |||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Studies

Anxiety in Children (ClinicalTrials.gov)

Studies looking at better understanding, diagnosing, and treating this condition; from the National Library of Medicine.

Helpful Articles

PubMed search for anxiety disorders in children, last 2 years

Hoge E, Bickham D, Cantor J.

Digital Media, Anxiety, and Depression in Children.

Pediatrics.

2017;140(Suppl 2):S76-S80.

PubMed abstract

Strawn JR, Dobson ET, Giles LL.

Primary pediatric care psychopharmacology: focus on medications for ADHD, depression, and anxiety.

Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care.

2017;47(1):3-14.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Santilhano M.

Online intervention to reduce pediatric anxiety: An evidence-based review.

J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs.

2019;32(4):197-209.

PubMed abstract

Doyle MM.

Anxiety Disorders in Children.

Pediatr Rev.

2022;43(11):618-630.

PubMed abstract

Authors & Reviewers

| Author: | Matthew Koster, DO, MBA |

| 2020: update: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPA; Mary Steinmann, MD, FAAP, FAPAR |

| 2016: first version: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPA; Mary Steinmann, MD, FAAP, FAPAR |

Page Bibliography

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.

Psychiatric medication for children and adolescents: part II - types of medications.

(2017)

http://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-G.... Accessed on 5/5/2020.

American Psychiatric Association.

Diagnostic And Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR).

Fifth Edition ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing;

2022.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

American Psychiatric Association: DSM-5 Task Force.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Fifth ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing;

2013.

http://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425...

Bagnell AL.

Anxiety and separation disorders.

Pediatr Rev.

2011;32(10):440-5; quiz 446.

PubMed abstract

Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS.

Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V.

Psychiatr Clin North Am.

2009;32(3):483-524.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Hérot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, Kagan J, Faraone SV.

Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children.

Am J Psychiatry.

2001;158(10):1673-9.

PubMed abstract

Cohen JA, Bukstein O, Walter H, Benson SR, Chrisman A, Farchione TR, Hamilton J, Keable H, Kinlan J, Schoettle U, Siegel M,

Stock S, Medicus J.

Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2010;49(4):414-30.

PubMed abstract

Connolly SD, Bernstein GA.

Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2007;46(2):267-83.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Doyle MM.

Anxiety Disorders in Children.

Pediatr Rev.

2022;43(11):618-630.

PubMed abstract

Dulcan MK, Ballard R.

Medication Information for Parents and Teachers: Propranolol—Inderal.

American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; (2015)

http://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370283.m.... Accessed on 5/5/2020.

From Helping Parents and Teachers Understand Medications for Behavioral and Emotional Problems: A Resource Book of Medication

Information Handouts, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2015-subscription required.

Durham RC, Higgins C, Chambers JA, Swan JS, Dow MG.

Long-term outcome of eight clinical trials of CBT for anxiety disorders: symptom profile of sustained recovery and treatment-resistant

groups.

J Affect Disord.

2012;136(3):875-81.

PubMed abstract

Earle JF.

An Introduction to the Psychopharmacology of Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder.

J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs.

2016;29(2):62-71.

PubMed abstract

Fourneret P, Desombre H, de Villard R, Revol O.

[Interest of propranolol in the treatment of school refusal anxiety: about three clinical observations].

Encephale.

2001;27(6):578-84.

PubMed abstract

Freedman R, Lewis DA, Michels R, Pine DS, Schultz SK, Tamminga CA, Gabbard GO, Gau SS, Javitt DC, Oquendo MA, Shrout PE, Vieta

E, Yager J.

The initial field trials of DSM-5: new blooms and old thorns.

Am J Psychiatry.

2013;170(1):1-5.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Geller D, March J.

Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2012;51(1):98-113.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, Ali MM, Lynch SE, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ.

Prevalence and Treatment of Depression, Anxiety, and Conduct Problems in US Children.

J Pediatr.

2019;206:256-267.e3.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

This article reviews data from the 2016 National Survey of Children's Health (NSCH) to report nationally representative prevalence

estimates of each condition among children aged 3-17 years and receipt of treatment by a mental health professional.

Grist R, Porter J, Stallard P.

Mental Health Mobile Apps for Preadolescents and Adolescents: A Systematic Review.

J Med Internet Res.

2017;19(5):e176.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Hoge E, Bickham D, Cantor J.

Digital Media, Anxiety, and Depression in Children.

Pediatrics.

2017;140(Suppl 2):S76-S80.

PubMed abstract

Houtrow AJ, Okumura MJ, Hilton JF, Rehm RS.

Profiling health and health-related services for children with special health care needs with and without disabilities.

Acad Pediatr.

2011;11(6):508-16.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Kathi J. Kemper.

Mental Health, Naturally: The Family Guide to Holistic Care for a Healthy Mind and Body.

1st ed. American Academy of Pediatrics;

2010.

1581103107 http://shop.aap.org/Mental-Health-Naturally-The-Family-Guide-to-Holist...

Kung S, Espinel Z, Lapid MI.

Treatment of nightmares with prazosin: a systematic review.

Mayo Clin Proc.

2012;87(9):890-900.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

León-Barriera R, Ortegon RS, Chaplin MM, Modesto-Lowe V.

Treating ADHD and Comorbid Anxiety in Children: A Guide for Clinical Practice.

Clin Pediatr (Phila).

2023;62(1):39-46.

PubMed abstract

Manassis K, Hood J.

Individual and familial predictors of impairment in childhood anxiety disorders.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

1998;37(4):428-34.

PubMed abstract

McClafferty H, Sibinga E, Bailey M, Culbert T, Weydert J, Brown M.

Mind-Body Therapies in Children and Youth.

Pediatrics.

2016;138(3).

PubMed abstract

This AAP Section on Integrative Medicine clinical report outlines popular mind-body therapies for children and youth and examines

the best-available evidence for a variety of mind-body therapies and practices, including biofeedback, clinical hypnosis,

guided imagery, meditation, and yoga. The report is intended to help health care professionals guide their patients to nonpharmacologic

approaches to improve concentration, help decrease pain, control discomfort, or ease anxiety; American Academy of Pediatrics.

Merikangas KR, Avenevoli S, Dierker L, Grillon C.

Vulnerability factors among children at risk for anxiety disorders.

Biol Psychiatry.

1999;46(11):1523-35.

PubMed abstract

Mossman SA, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK, Varney ST, Fleck DE, Barzman DH, Gilman R, DelBello MP, Strawn JR.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: Signal detection and validation.

Ann Clin Psychiatry.

2017;29(4):227-234A.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

This study evaluates a brief, self-report scale—the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale (GAD-7)—in adolescents with

generalized anxiety disorder.

Nutter D.

Pediatric Generalized Anxiety Disorder Medication.

Medscape; (2016)

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/916933-medication#1. Accessed on 5/5/20.

Perry PJ, Wilborn CA.

Serotonin syndrome vs neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a contrast of causes, diagnoses, and management.

Ann Clin Psychiatry.

2012;24(2):155-62.

PubMed abstract

Piacentini J, Bennett S, Compton SN, Kendall PC, Birmaher B, Albano AM, March J, Sherrill J, Sakolsky D, Ginsburg G, Rynn

M, Bergman RL, Gosch E, Waslick B, Iyengar S, McCracken J, Walkup J.

24- and 36-week outcomes for the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS).

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2014;53(3):297-310.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Rapee RM, Creswell C, Kendall PC, Pine DS, Waters AM.

Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: A summary and overview of the literature.

Behav Res Ther.

2023;168:104376.

PubMed abstract

Santilhano M.

Online intervention to reduce pediatric anxiety: An evidence-based review.

J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs.

2019;32(4):197-209.

PubMed abstract

Smoller JW.

The Genetics of Stress-Related Disorders: PTSD, Depression, and Anxiety Disorders.

Neuropsychopharmacology.

2016;41(1):297-319.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Strawn JR, Dobson ET, Giles LL.

Primary pediatric care psychopharmacology: focus on medications for ADHD, depression, and anxiety.

Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care.

2017;47(1):3-14.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Strawn JR, Sakolsky DJ, Rynn MA.

Psychopharmacologic treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders.

Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am.

2012;21(3):527-39.

PubMed abstract

Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, Ginsburg GS, Rynn MA, McCracken J, Waslick B, Iyengar

S, March JS, Kendall PC.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety.

N Engl J Med.

2008;359(26):2753-66.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Walter HJ, Bukstein OG, Abright AR, Keable H, Ramtekkar U, Ripperger-Suhler J, Rockhill C.

Clinical practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2020;59(10):1107-1124.

PubMed abstract

Wang Z, Whiteside SPH, Sim L, Farah W, Morrow AS, Alsawas M, Barrionuevo P, Tello M, Asi N, Beuschel B, Daraz L, Almasri J,

Zaiem F, Larrea-Mantilla L, Ponce OJ, LeBlanc A, Prokop LJ, Murad MH.

Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Pharmacotherapy for Childhood Anxiety Disorders:

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

JAMA Pediatr.

2017;171(11):1049-1056.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Wehry AM, Beesdo-Baum K, Hennelly MM, Connolly SD, Strawn JR.

Assessment and treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents.

Curr Psychiatry Rep.

2015;17(7):52.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Get Help in Rhode Island

Get Help in Rhode Island