Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

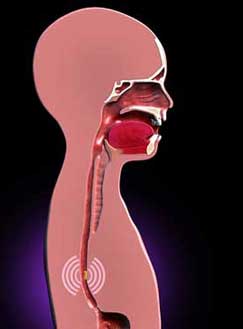

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is a physiologic process in which the stomach contents pass into the esophagus with or without regurgitation and/or vomiting; gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined by the troublesome symptoms or complications that result from reflux, such as esophagitis or esophageal strictures. [Rosen: 2018] Refractory GERD is GERD that does not improve after 8 weeks of optimal treatment. [Rosen: 2018] Although not completely understood, the mechanisms for reflux may include abnormal esophageal motility and delayed gastric emptying, possibly exacerbated by constipation.

GER and GERD are common in children and adolescents with special health care needs, particularly in children with prematurity, neurological impairment, obesity, repaired esophageal atresia, hiatal hernia, achalasia, and chronic respiratory disorders that include bronchopulmonary dysplasia (chronic lung disease of prematurity), idiopathic interstitial fibrosis, and cystic fibrosis. [Lightdale: 2013]

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical symptoms and signs suggestive of GERD vary by age. Infants (0-12 months old) may experience regurgitation and vomiting with: [Lightdale: 2013]

|

|

In premature infants, typical symptoms of GERD (apnea and desaturations, feeding intolerance, oral aversion, irritability, discomfort after feeds, and poor weight gain) rarely correspond with actual reflux episodes including both acidic and non-acidic events measured with a pH probe. [Eichenwald: 2018]

Children (1-5 years old) may experience: [Lightdale: 2013]

- Regurgitation or vomiting, which can lead to poor weight gain or nutritional deficiencies

- Feeding refusal or decreased appetite

- Abdominal pain

Children (6-18 years old) may experience: [Lightdale: 2013]

|

|

Evaluation

If the medical history and physical examination strongly suggest GERD and there are no other flags, empiric treatment (with lifestyle changes prior to medication use) without specific evaluation is often appropriate. Consider empirical treatment of constipation if it is a concern. Management information for constipation in children can be found in the Portal's Constipation module. For pediatric GERD that is refractory to medications after 4-8 weeks (and definitely if requiring therapy >6-12 months), referral is advised. To evaluate for anatomical and histologic etiologies, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsies and upper GI studies may be recommended.

Differential Diagnoses

|

|

Screening and Testing

- Determine if the patient should be tested on or off reflux medications

- Reliably define reference ranges

- Determine if the study influences outcomes

- Salivary pepsin – lacks sensitivity and normative data

- Lipid-laden macrophage index – lacks evidence as a biomarker for reflux

- Bilirubin in the esophagus –fiber optics used in the study impair normal digestion

Treatment

Lifestyle Changes

- Offer smaller, more frequent feeds.

- Thicken breastmilk or formula. Use of thickeners for infants with reflux lacks quality evidence. Expert opinion is that thickened feeds improve visible regurgitation but do not alter the acid reflux burden assessed by pH-MII. [Rosen: 2018] Keep in mind that thickening breastmilk and formula increases caloric density. Little is known about the long-term effects of using thickeners. See Thickened Liquids & Modified Foods

- For breastfed infants, remove dairy products, including casein and whey, from the maternal diet for 2-4 weeks to determine if a protein allergy may be causing reflux-like symptoms.[Rosen: 2018] Egg, soy, or wheat exclusion may also be considered if balanced with the mother's nutritional needs.

- In formula-fed infants, initiate a trial of extensively hydrolyzed formula for at least 2 weeks. An amino-acid-based formula could be trialed if an extensively hydrolyzed formula. Use of soy formula for this purpose is not advised due to the frequency of soy protein intolerance in infants with cow milk protein allergy. [Rosen: 2018] See Formulas for examples of brands.

- Consider head elevation or positioning the awake infant in the left-lateral lying position during and after feeds [Rosen: 2018], or prone while observed and awake. Supine and semi-supine positions, such as in a car seat, increase reflux. Positioning recommendations mostly are based on pH probe or pH/impedance studies. The AAP advises against using commercial positioners to elevate the infant’s head due to risk for SIDS (sudden Infant death syndrome). [Lightdale: 2013] [Eichenwald: 2018]

- Eliminate second- and third-hand smoke exposure (residue from tobacco products that is left behind after smoking). The chemicals increase the risk of gastrointestinal dysregulation. [Shenassa: 2004] This intervention has little evidence related to GERD, but it is a no-risk option.

- Prebiotics and probiotics, as well as herbal medicines and complementary therapies, do not have enough evidence for safe treatment of infant GERD. Probiotics (L. reuteri) used preventatively in one study reduced crying time and number of regurgitations; however, these symptoms are not specific to GERD. [Rosen: 2018]

- Reduce excess body weight to reduce pressure on the esophageal sphincter. [Rosen: 2018]

- No smoking. Avoid second- and third-hand smoke exposure.

- Avoid alcohol use

- Avoid foods that may increase reflux (chocolate, peppermint, onions, garlic) and spicy, fatty, or acidic (citrus- or tomato-based) foods.

- Chew sugarless gum after meals to promote motility. [Lightdale: 2013]

- Adjustments in feeding schedule (reducing bolus sizes, limiting feedings given in the recumbent position, and continuous nocturnal feedings) may be helpful.

- Switching to transpyloric (e.g., gastrostomy-jejunal) tube feeds is often done for intractable reflux symptoms. [Rosen: 2018] [Campwala: 2015]

- In children with neurologic impairment, transpyloric feeding reduces the reflux burden about the same as a fundoplication.[Stone: 2017] Experts suggest that transpyloric feedings may be considered as treatment options for patients refractory to medications. [Rosen: 2018]

Medications

- For infants, use of anti-reflux medications is usually considered as a last resort after attempting lifestyle changes. [Lightdale: 2013] Current expert opinion recommends consultation of a pediatric gastroenterologist, when available, prior to starting anti-reflux medications in infants. When using medications, the general advice is to proceed with caution and limit duration of therapy. For premature infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), avoid use of medications because clinical symptoms are unreliable indicators of true reflux, and using reflux medications in this population has limited benefits and increased risks, such as necrotizing enterocolitis. [Eichenwald: 2018]

- For medically complex children who may require long-term medication use for GERD, frequently review the benefits and risks with caregivers and attempt to wean medications, whenever possible, in coordination with the child’s specialists. Use of medications for treatment of GERD in children, particularly in children with neurodisability, has limited high-quality evidence. [Tighe: 2014]

- Over-the-counter formulations for acid suppression and prokinetic agents are available.

Acid Suppressants

H2 Receptor Antagonists (H2RA)

While many consider PPIs to be the most effective for treatment of GERD, H2Ras (aka H2 blockers) usually cost less and are covered more by insurers (who may require treatment failure with H2RAs before authorizing coverage for a PPI). When taken orally, H2RAs offer faster relief than PPIs and start working within an hour to neutralize acid and relieve reflux pain. The effect lasts 10-12 hours. Administration is typically 2 times daily (BID) at meals or bedtime, or 3 times daily in smaller doses for children whose symptoms recur quickly.

Experts recommend limited use of H2RAs (4-8 weeks) in children with typical symptoms of GERD, but not for extraesophageal symptoms (e.g., cough, wheezing, asthma) without typical GERD symptoms or suggestive diagnostic testing. Experts also advise against the use of H2RAs for otherwise healthy infants who have excessive crying or frequent regurgitation. [Rosen: 2018] Be aware that H2RAs may impair iron absorption.

Long-term use can induce tachyphylaxis or tolerance. [Vandenplas: 2009] Risks of longer-term use can include vitamin B12 deficiency and increased risk for developing gastroenteritis and pneumonia. Use caution in patients with renal or hepatic impairment. Consult a drug reference due to multiple interactions with other drugs. Frequent evaluation of children on long-term acid suppression is advised.

Ranitidine (Zantac)

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requested

that all prescription and over-the-counter ranitidine (Zantac) products be

pulled from the market in 2020. An ongoing investigation uncovered levels of

N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a probable human carcinogen, which seems to

increase over time, especially when stored at higher room temperatures. The

agency urges patients and providers to consider taking alternative

medications. See FDA Updates and Press Announcements about NDMA in Zantac (ranitidine) & Axid (nizatidine).

Famotidine (Pepcid) [Lightdale: 2013]

- Considerations: FDA indicated for ages 0 and older for treatment of GERD. Benzyl alcohol solution is associated with adverse events in neonates. Torsades de pointes has been associated with use of famotidine in patients with renal impairment.

- Formulations: Cherry-banana-mint solution (40 mg/5 mL) and tablets (10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg), max 40 mg/day

- Dosing:

- Infants <3 months: 0.5 mg/kg/dose given once daily due to prolonged elimination half-life in infants <3 months

- For infants >=3 months and children: 0.5 mg/kg/day divided BID, may increase up to 1 mg/kg/day divided BID, max 40 mg/day

Nizatidine (Axid) [Lightdale: 2013]

- Considerations: FDA indicated for ages ≥12 years. A voluntary recall of nizatidine started in 2020 due to detection of an impurity known as N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA); check the FDA drug safety updates (FDA Updates and Press Announcements about NDMA in Zantac (ranitidine) & Axid (nizatidine)) prior to prescribing this medication.

- Formulations: Bubble-gum flavored solution (15 mg/1 mL), capsules (150 mg, 300 mg), and tablets (75 mg)

- Dosing: 5-10 mg/kg/day divided BID, max 300 mg/day,

or:

- ≥12 years old: 150 mg BID

Cimetidine (Tagamet) [Lightdale: 2013]

- Considerations: FDA indicated for ages ≥16 years

- Formulations: Solution (300 mg/5 mL) and tablets (200 mg, 300 mg, 400 mg, 800 mg)

- Dosing: 30–40 mg/kg/d, divided in 4 doses, max 800

mg/day, or:

- Infants: 10-20 mg/kg/day divided every 6-12 hours

- Children: 20-40 mg/kg/day in divided doses every 6 hours

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

PPIs work in the stomach to prevent gastric acid production, thus alleviating pain associated with acid reflux. Moderate evidence supports short-term use (1-2 months) of PPIs in children with GERD [Tighe: 2014], but not for extraesophageal symptoms (e.g., cough, wheezing, asthma) without typical GERD symptoms or suggestive diagnostic testing. [Rosen: 2018]

PPIs are more highly recommended than H2RAs for GERD with erosive esophagitis. If costs, availability, or contraindications are a concern, then H2RAs are a reasonable alternative. No evidence demonstrates a clear benefit for PPI use in infants to help with crying, irritability, or visible regurgitation. [Chen: 2012] [Rosen: 2018]

Depending on the formulation, PPIs are given 30-60 minutes before breakfast. Since symptom relief is slower (1-5 hours) than H2RAs and antacids and the effect can last 3-5 days, PPIs are usually given daily to achieve a steady effect and not used for an as-needed/quick-relief effect. Insurers may require prescribers to demonstrate the patient’s lack of response to less costly H2RAs and receive prior authorization before covering PPIs.

PPIs historically have been considered safe; however, prescribers are growing increasingly concerned about risks with long-term use. Risks may include enteric infections, including Clostridium difficile, dysbiosis (an imbalance of microflora in the body), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, acute interstitial nephritis, lower levels of vitamin B12, magnesium, and calcium, and possibly pneumonia in infants. [Scarpignato: 2016] Frequent reevaluation of children on long-term acid suppressants is advised.

Use additional caution when prescribing these medications for children with liver disease or children taking anticoagulants, seizure medications, antibiotics, chemo agents, and other medications. Since PPIs work in the stomach, children with feeding tubes that bypass the stomach may not benefit from use.

Lansoprazole (Prevacid, First-Lansoprazole) [Lightdale: 2013] [Rosen: 2018]

- Considerations: FDA indicated for 1 year and older

- Formulations: Capsules (15 mg, 30 mg) that can be swallowed whole, sprinkled on soft food, dissolved in certain juices, or used for a nasogastric tube, and strawberry-flavored orally disintegrating tablets (15 mg, 30 mg) that can be dissolved and delivered via syringe or a nasogastric tube

- Dosing: 3 months-13 years: 1.4 mg/kg/day (range 0.7–3 mg/kg/day) once daily. Younger infants requiring PPI use may be dosed

at 0.5-1 mg/kg/day, or:

- ≥3 months old - 7.5 mg BID or 15 mg once daily

- 1-11 years old - ≤30 kg: 15 mg once daily; >30 kg: 30 mg once daily

- ≥12 years old-adolescents - 15 mg once daily

- Max 30 mg/day

- Considerations: FDA indicated for 1 year and older

- Formulations: Delayed-release capsules (10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg) (can sprinkle into soft foods); delayed-release tablets (20 mg) (swallow whole); packets (2.5 mg, 10 mg) (reconstitute with water for each dose – recommended if using a nasogastric tube); and suspension (compounded to 2 mg/1 mL). FDA indicated for ages ≥2 years.

- Dosing: 1-4 mg/kg/day, or:

- 5 kg - <10 kg - 5 mg once daily

- 10 kg - ≤20 kg - 10 mg once daily

- >20 kg: 20 mg - once daily, or 1 mg/kg/dose once or BID

- Max 40 mg/day

- Considerations: FDA indicated for ages ≥1 year

- Formulations: Delayed-release capsules (20 mg, 40 mg) (can open and sprinkle contents into soft foods or used for nasogastric tube; delayed release tablets (20 mg) (swallow whole); and packets (2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg) (ok for nasogastric tube)

- Dosing: <20 kg – 10 mg once daily, >=20 kg – 20 mg once daily, or:

- 1-11 years old - 10 mg

- ≥12 years old - 20 mg

- Max 40 mg/day

- Considerations: FDA indicated for ages ≥12 years

- Formulations: Capsules (5 mg, 10 mg) (sprinkle contents into soft food) and tablets (10 mg, 20 mg).

- Dosing:

- 1-11 years - <15 kg: 5-10 mg once daily; ≥15 kg: 10 mg once daily

- ≥12 years-adolescents - 20 mg once daily.

- Considerations: FDA indicated for pediatric GERD with history of erosive esophagitis

- Formulations - Tablets (20 mg, 40 mg) and delayed-release granules for oral suspension (40 mg in a unit dose packet) (mix with applesauce or apple juice, or used for nasogastric tube)

- Dosing -≥5 years - 1-2 mg/kg/day, or:

- 15-39 kg: 20 mg orally once a day

- ≥40 kg: 40 mg orally once a day

- Max 40 mg/day

Antacids and Alginates

Over-the-counter medications used for occasional reflux symptoms include acid neutralizers (e.g., Tums) and other types of

medications (alginates or sucralfate) that coat the surface of the stomach. Alginates have demonstrated slight improvement

in visible regurgitation and vomiting in pediatric GERD; the side effects of long-term treatment are unknown. [Rosen: 2018] Expert opinion is that alginates could be trialed for as needed (PRN) or short-term use. Though other antacids are commonly

used for symptomatic relief in adults and sometimes to help determine if the child’s symptoms improve with acid neutralization,

these medications are not recommended for use in children and can result in toxicity from components such as calcium or aluminum.

[Lightdale: 2013]

[Rosen: 2018]

Prokinetics

Slow gut motility can prolong gastric emptying and contribute to retrograde flow of stomach contents into the esophagus, potentially causing irritation and inflammation. If impaired gut motility is suspected to be contributing to a child’s reflux symptoms (e.g., in those with neurological impairments like cerebral palsy), prokinetic agents may reduce reliance on acid suppressants or be used as adjuvant therapy; however, evidence is lacking about efficacy, potential side effects, and safety risks. Effectively managed constipation is an essential precursor to use of a prokinetic because stool clogging the intestines could block the passage of stomach contents. Details about management of constipation in children can be found in the Portal's Constipation.

Due to the risks associated with these medications, strongly consider consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist prior to initiating therapy with a prokinetic agent. Dosing guidelines are provided here only for erythromycin ethylsuccinate, which is considered the safest option.

Erythromycin Ethylsuccinate (EES)

Initially developed as an antibiotic, researchers found that

low-dose EES stimulates the hormone motilin, which results in increased

contractions in the antrum of the stomach and faster gastric emptying.

Low-dose EES may have better efficacy than metoclopramide with increasing

gastric motility.

- Considerations: Common side effects include gastrointestinal upset and rashes. When used for chronic treatment, tachyphylaxis may develop, so 2-week breaks are frequently employed. [Waseem: 2009] EES increases the risk of cardiac toxicity, particularly when used with certain other medications, including antipsychotics, and when used at antibiotic doses. [Ericson: 2015] EES use in neonates in the first 2 weeks of life is associated with increased risk for pyloric stenosis. Consider electrocardiograph monitoring before treatment and periodically during treatment; avoid use in patients with prolonged QT interval.

- Formulations: Various fruit-flavored suspensions (200 mg/5 mL, 400 mg/5 mL); tablets (200 mg, 400 mg, 500 mg); and delayed release tablets (250 mg, 333 mg, 500 mg) [Lightdale: 2013]

- Dosing: 3 mg/kg/dose 4 times daily (may increase as needed to effect); maximum dose: 10 mg/kg or 250 mg [Lightdale: 2013] or 3-5 mg/kg/dose 3-4 times daily

Azithromycin

Azithromycin has been used by pediatric gastroenterologists as an alternative to EES in certain cases. Consultation with a

pediatric gastroenterologist is recommended before starting azithromycin for motility.

Baclofen

After other medications have failed, baclofen may be considered prior to a surgical intervention for GERD. [Rosen: 2018] This GABA-B receptor antagonist is typically used to reduce muscle spasticity; it also can improve gastric motility and reduce

relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter, which prevent some refluxing episodes. Therefore, a seizure-free child with

reflux (related to slow motility), cerebral palsy, and spasticity may be an ideal candidate for using baclofen and may receive

dual benefit from using this medication.

Side effects include sedation and lowered seizure threshold. Consultation with a pediatric rehabilitation medicine specialist (physiatrist) is recommended when using baclofen to treat spasticity (Pediatric Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation (see RI providers [6])).

Metoclopramide (Reglan)

Experts generally advise against use of metoclopramide for treatment of pediatric GERD. [Rosen: 2018]

Metoclopramide may mediate its impact through increased lower esophageal sphincter pressure, accelerated gastric emptying,

and increased small bowel peristalsis. Metoclopramide also has centrally acting anti-emetic properties.

In a large percentage of children, metoclopramide can cause significant central nervous system side effects that include fatigue, restlessness, tremors, increased tone, extrapyramidal reactions (dystonic, oculogyric crisis), and tardive dyskinesia. Monitor for irritability, sedation, diarrhea, increased emesis/feeding intolerance, and neurological symptoms. There is a black box warning due to the risk of tardive dyskinesia.

Cisapride

Because severe cardiac arrhythmias (e.g., ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, torsades de pointes, and QT prolongation)

have been reported in patients taking cisapride, this medication is only available through a limited access protocol or as

part of a clinical trial. This medication may be considered by a pediatric gastroenterologist for use with certain patients.

Domperidone

Due to the risk of multiple severe side effects, this medication is not available in the United States. Experts generally

advise against the use of domperidone for treatment of pediatric GERD. [Rosen: 2018]

Bethanechol

Mentioned in the pediatric GERD guideline [Rosen: 2018], this medication is not commonly used.

Surgical Therapy

Subspecialist Collaborations

Consider referral to Pediatric Gastroenterology (see RI providers [18]) for:

- Recurrent, severe symptoms

- Failure of empiric therapy

- GI bleeding

- If a feeding tube or reflux surgery (e.g., Nissen fundoplication) is being considered

- Iron deficiency associated with chronic esophagitis

- Consideration of other diagnoses

- Determining most useful studies for further evaluation

Resources

Information & Support

Related Issues

- Missing link with id: 99e6f817.xml

- Constipation

For Professionals

Acid Reflux in Children with Autism (Autism Speaks)

A video about recognizing the signs of reflux in children with autism; presented by GI Specialist Tim Buie, director of Pediatric

Gastroenterology and Nutrition at MassGeneral Hospital’s Lurie Center for Autism.

For Parents and Patients

Acid Reflux (GER and GERD) in Children and Teens (NIDDK)

Extensive information that includes symptoms, causes, diagnosis, treatment, and diet (use menu on left of the webpage); National

Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Practice Guidelines

Eichenwald EC.

Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Preterm Infants.

Pediatrics.

2018;142(1).

PubMed abstract

Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, Cabana M, DiLorenzo C, Gottrand F, Gupta S, Langendam M, Staiano A, Thapar N, Tipnis

N, Tabbers M.

Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric

Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2018;66(3):516-554.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Patient Education

Let's Talk About... Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) in Infants (Spanish & English)

A 3-page patient handout in Spanish and English about GERD in infants and toddlers; Intermountain Healthcare.

Let's Talk About... pH Probe Study: Acid Reflux Test (Spanish & English)

A 2-page handout explaining the pediatric pH probe procedure; Intermountain Healthcare.

Let's Talk About... When Drinking or Eating is Not Safe (Spanish & English)

A 2-page patient handout in Spanish and English about aspiration and the modified barium study procedure; Intermountain Healthcare.

Services for Patients & Families in Rhode Island (RI)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | RI | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NM | NV | UT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 18 | 2 | 5 | 2 | ||||

| Pediatric Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | |||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Studies

Clinical trials in children and adolescents with GERD (clinicaltrials.gov)

Studies looking at better understanding, diagnosing, and treating this condition; from the National Library of Medicine.

Helpful Articles

PubMed search for gastroesophageal reflux disease in children, last 1 year.

Lightdale JR, Gremse DA.

Gastroesophageal reflux: management guidance for the pediatrician.

Pediatrics.

2013;131(5):e1684-95.

PubMed abstract

Tighe M, Afzal NA, Bevan A, Hayen A, Munro A, Beattie RM.

Pharmacological treatment of children with gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2014;11:CD008550.

PubMed abstract

Scarpignato C, Gatta L, Zullo A, Blandizzi C.

Effective and safe proton pump inhibitor therapy in acid-related diseases - A position paper addressing benefits and potential

harms of acid suppression.

BMC Med.

2016;14(1):179.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Authors & Reviewers

| Author: | Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAP |

| Reviewer: | Molly O'Gorman, MD |

| 2018: update: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPA; Molly O'Gorman, MDR |

| 2017: first version: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPA; Molly O'Gorman, MDR |

Page Bibliography

Campwala I, Perrone E, Yanni G, Shah M, Gollin G.

Complications of gastrojejunal feeding tubes in children.

J Surg Res.

2015;199(1):67-71.

PubMed abstract

Chen IL, Gao WY, Johnson AP, Niak A, Troiani J, Korvick J, Snow N, Estes K, Taylor A, Griebel D.

Proton pump inhibitor use in infants: FDA reviewer experience.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2012;54(1):8-14.

PubMed abstract

Deal L, Gold BD, Gremse DA, Winter HS, Peters SB, Fraga PD, Mack ME, Gaylord SM, Tolia V, Fitzgerald JF.

Age-specific questionnaires distinguish GERD symptom frequency and severity in infants and young children: development and

initial validation.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2005;41(2):178-85.

PubMed abstract

Eichenwald EC.

Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Preterm Infants.

Pediatrics.

2018;142(1).

PubMed abstract

Ericson JE, Arnold C, Cheeseman J, Cho J, Kaneko S, Wilson E, Clark RH, Benjamin DK Jr, Chu V, Smith PB, Hornik CP.

Use and Safety of Erythromycin and Metoclopramide in Hospitalized Infants.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2015;61(3):334-9.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Hirano I, Pandolfino JE, Boeckxstaens GE.

Functional Lumen Imaging Probe for the Management of Esophageal Disorders: Expert Review From the Clinical Practice Updates

Committee of the AGA Institute.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

2017;15(3):325-334.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

The aim of this Clinical Practice Update is to describe the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) technique and review

potential indications in achalasia, eosinophilic esophagitis and GERD; American Gastroenterological Association.

Kleinman L, Revicki DA, Flood E.

Validation issues in questionnaires for diagnosis and monitoring of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children.

Curr Gastroenterol Rep.

2006;8(3):230-6.

PubMed abstract

Lightdale JR, Gremse DA.

Gastroesophageal reflux: management guidance for the pediatrician.

Pediatrics.

2013;131(5):e1684-95.

PubMed abstract

Riley AW, Trabulsi J, Yao M, Bevans KB, DeRusso PA.

Validation of a Parent Report Questionnaire: The Infant Gastrointestinal Symptom Questionnaire.

Clin Pediatr (Phila).

2015;54(12):1167-74.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, Cabana M, DiLorenzo C, Gottrand F, Gupta S, Langendam M, Staiano A, Thapar N, Tipnis

N, Tabbers M.

Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric

Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2018;66(3):516-554.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Scarpignato C, Gatta L, Zullo A, Blandizzi C.

Effective and safe proton pump inhibitor therapy in acid-related diseases - A position paper addressing benefits and potential

harms of acid suppression.

BMC Med.

2016;14(1):179.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Shenassa ED, Brown MJ.

Maternal smoking and infantile gastrointestinal dysregulation: the case of colic.

Pediatrics.

2004;114(4):e497-505.

PubMed abstract

Stone B, Hester G, Jackson D, Richardson T, Hall M, Gouripeddi R, Butcher R, Keren R, Srivastava R.

Effectiveness of Fundoplication or Gastrojejunal Feeding in Children With Neurologic Impairment.

Hosp Pediatr.

2017;7(3):140-148.

PubMed abstract

Tighe M, Afzal NA, Bevan A, Hayen A, Munro A, Beattie RM.

Pharmacological treatment of children with gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2014;11:CD008550.

PubMed abstract

Vandenplas Y et. al.

Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric

Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology,

and Nutrition (ESPGHAN).

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2009;49(4):498-547.

PubMed abstract

Waseem S, Moshiree B, Draganov PV.

Gastroparesis: current diagnostic challenges and management considerations.

World J Gastroenterol.

2009;15(1):25-37.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Get Help in Rhode Island

Get Help in Rhode Island