Autism Spectrum Disorder

Overview

Other Names & Coding

F84.0, Autistic disorder

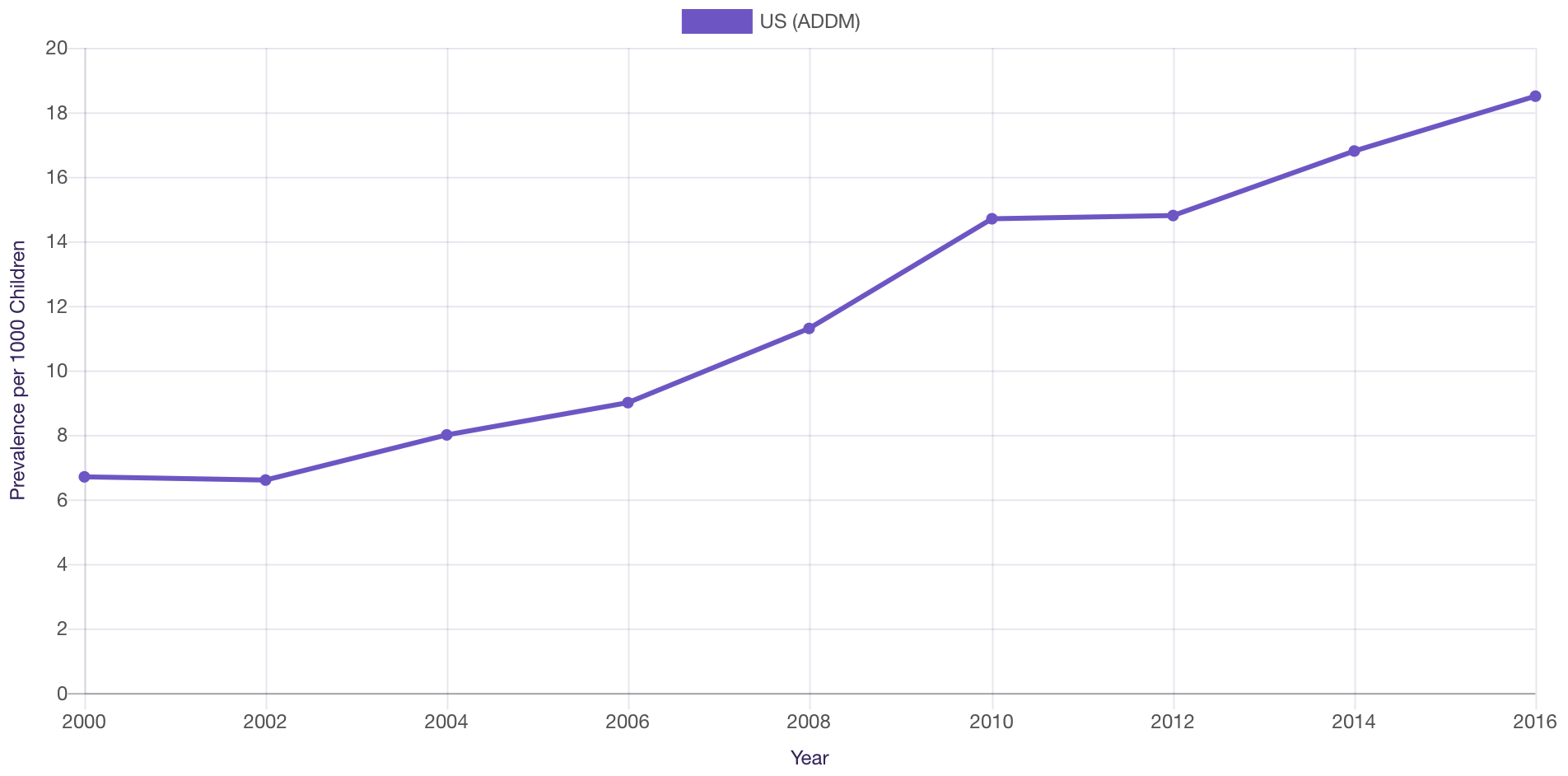

Prevalence

Prevalence of ASD in the US (2000-2016)

Genetics

The likelihood of a genetic abnormality increases if the patient has co-occurring intellectual disability and/or dysmorphic features on physical exam. [Schaefer: 2016] In 6-15% of cases, ASD is associated with a medical condition or known syndrome, such as trisomy 21, fragile X syndrome, or tuberous sclerosis complex. The majority of cases, however, have no clear etiology. [Schaefer: 2013] For a comprehensive review of the genes known to be associated with ASD, see Autism Spectrum Disorder (OMIM).

Parents who have 1 child with ASD should be counseled about the risk for subsequent children. Depending upon whether a specific genetic cause has been identified, the risk for subsequent children having ASD is thought to be 7-19%. [Palmer: 2017] [Grønborg: 2013] [Ozonoff: 2011] Yet, a study from the UK suggests that the recurrence risk is much higher when parents stop reproducing after a diagnosis is received is taken into account (24.7% overall and 50.0% in families with 2 or more older siblings with ASD). [Wood: 2015]

Prognosis

Favorable prognostic factors include early language acquisition, joint attention and typical range cognition. Approximately 9% of individuals diagnosed with ASD during childhood will have “optimal outcomes,” defined as not meeting DSM criteria when later evaluated. Factors associated with optimal outcomes include early and intensive ABA therapy and higher initial cognitive skills. [Orinstein: 2014] Some children with ASD may have a more static developmental trajectory and be more prone to maladaptive behaviors. These outcomes are associated with the presence of intellectual disability, epilepsy, no functional use of language by 5 years, comorbid medical/genetic conditions, and comorbid psychiatric disorders. [Hyman: 2020] [Anderson: 2014]

A 20-year, follow-up study of adults with autism and average or near-average intellectual abilities found that half were rated as functioning on a “good” or “very good” level based on a global outcome measure; 54% were employed in full- or part-time jobs. Despite this, only about 12% lived independently and 56% lived with their parents. [Farley: 2009] About 75% of children with both intellectual disability and ASD require long-term social and educational supports. [Mefford: 2012]

Practice Guidelines

The following clinical reports from the American Academy of

Pediatrics, American Academy of Neurology and Child Neurology Society, and

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry provide detailed information

and guidelines regarding the diagnosis and management of ASD.

Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM.

Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Pediatrics.

2020;145(1).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

McGuire K, Fung LK, Hagopian L, Vasa RA, Mahajan R, Bernal P, Silberman AE, Wolfe A, Coury DL, Hardan AY, Veenstra-VanderWeele

J, Whitaker AH.

Irritability and Problem Behavior in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Practice Pathway for Pediatric Primary Care.

Pediatrics.

2016;137 Suppl 2:S136-48.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Furuta GT, Williams K, Kooros K, Kaul A, Panzer R, Coury DL, Fuchs G.

Management of constipation in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders.

Pediatrics.

2012;130 Suppl 2:S98-105.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Malow BA, Byars K, Johnson K, Weiss S, Bernal P, Goldman SE, Panzer R, Coury DL, Glaze DG.

A practice pathway for the identification, evaluation, and management of insomnia in children and adolescents with autism

spectrum disorders.

Pediatrics.

2012;130 Suppl 2:S106-24.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Mahajan R, Bernal MP, Panzer R, Whitaker A, Roberts W, Handen B, Hardan A, Anagnostou E, Veenstra-VanderWeele J.

Clinical practice pathways for evaluation and medication choice for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in autism

spectrum disorders.

Pediatrics.

2012;130 Suppl 2:S125-38.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Vasa RA, Mazurek MO, Mahajan R, Bennett AE, Bernal MP, Nozzolillo AA, Arnold LE, Coury DL.

Assessment and treatment of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders.

Pediatrics.

2016;137 Suppl 2:S115-23.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Roles of the Medical Home

Clinical Assessment

Overview

- Provide ongoing developmental surveillance at every well-child visit.

- Implement autism screening at 18 and 24 months.

- Develop a plan for referral and further evaluation of children who have a positive screen or a family member or clinician with concerns.

- Early diagnosis of ASD can facilitate earlier interventions, potentially leading to better outcomes. [Dawson: 2008]

- Even though ASD can be diagnosed as early as age 2 years, most children are not diagnosed with ASD until after age 3 to 4 years, when eligibility for early intervention services expires. [Goodwin: 2017]

- Rural communities face many barriers to care. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities include significant challenges to accessing diagnostic, treatment, and support services. [Zwaigenbaum: 2009]

Pearls & Alerts for Assessment

Flags for the immediate evaluation of autismThe following "red flags" are absolute indications for an immediate evaluation for autism: [Hyman: 2020] [Centers: 2019]

- ANY loss of ANY language or social skills at ANY age. [Hyman: 2020] See Learn the Signs Act Early (CDC) for skills by age.

- By 12 months: Does not respond to name

- By 14 months: Does not point at objects to show interest

- In general:

- Avoids eye contact and may want to be alone

- Has trouble understanding other people's feelings or talking about their feelings

- Has delayed speech and language skills

- Repeats words or phrases over and over (echolalia)

- Gives unrelated answers to questions

- Gets unusually upset by minor changes

- Has obsessive interests

- Makes repetitive movements like flapping hands, rocking, or spinning in circles

- Has unusual reactions to the way things sound, smell, taste, look, or feel

A score of "fail" on the M-CHAT or other screening tool is not diagnostic. A fail merits a follow-up questionnaire (M-CHAT-R/F, see below) to determine whether referral for a developmental evaluation is indicated.

Seizures can cause acute behavior changesConsider new-onset of seizure activity in a child with ASD as a possible cause of acute behavior changes. [Jeste: 2011] Risk of seizures among those with ASD ranges from 7-23%, and as high as 46%. Risk factors for the increased likelihood of seizures in people with ASD include intellectual disability, female sex, and lower gestational age. [Hyman: 2020]

Screening

For the Condition

Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers – Revised, with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F)

This commonly used, well-studied, and validated 2-step autism screen has questions about joint attention, pretend play, repetitive behaviors, and sensory abnormalities. It is more accurate than the previously used M-CHAT and CHAT when both steps are used.

- Format: 20-item, 5-10 minutes to complete with ~1 minute for scoring. An additional 5-10 minute follow-up interview is required for medium-risk respondents.

- Age range: 16–30 months of age

- Languages: >50 languages in printable version; English and Spanish in online versions

- Scoring: The initial step is administration of the M-CHAT-R/F to stratify into low-, medium, and high-risk categories. For medium-risk groups, the follow-up interviews improve specificity and determine need for referral.

- Sensitivity: Using an initial step with a cutoff of 3, sensitivity=73% and specificity=89%, but then adding the second step with a cutoff of 2 increased sensitivity to 94%. 47.5% of children referred for evaluation based on positive 2-step M-CHAT-R/F were diagnosed with an ASD. [Robins: 2014]

- Free to download or access online with instructions for scoring at Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers – Revised, with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F).

Of Family Members

For Complications

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all children with ASD should be screened yearly for sleep issues. [Malow: 2012] For screening tools, see the Portal’s Screening for Sleep Problems page.

Seizures

All children with ASD should be screened by history for a seizure disorder. Consider referral for EEG if history of regression is present in early development. In addition, normal hearing should always be documented in any child with an ASD diagnosis.

Psychiatric Disorders

In children and adolescents with autism, at least 72% had at least 1 additional psychiatric diagnosis; it is common to see more. Maintain a low threshold for considering psychiatric disorders. The common diagnoses and their frequencies, if known, in children with autism are below, along with links to relevant screening tools. [Leyfer: 2006]

- Specific phobia (44%)

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (37%)

- ADHD (31%) - Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Major depressive disorder (10%) - Depression

- Oppositional defiant disorder (7%)

- Psychotic disorders/schizophrenia (10%) - [Buck: 2014]

- Anxiety - Anxiety Disorders

- Mania - Child Mania Rating Scale (

247 KB) and Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (

247 KB) and Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale ( 36 KB)

36 KB)

Presentations

See DSM-5 [American: 2013] for details related to diagnostic features, including speech and language delay, social skills deficits, repetitive/stereotypic patterns of behavior, restricted interests, and atypical play skills. Autism Screening has suggestions for surveillance and screening.

Diagnostic Criteria

According to DSM-5, in order to meet criteria for ASD, one must have all 3 deficits in the social communication and social interaction domain and at least 2 of the 4 deficits in restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior domain.

| Social communication deficits (3/3) | Restricted interests/repetitive behaviors (2/4) |

|

|

- Level 1 (needs support)

- Level 2 (needs substantial support)

- Level 3 (needs very substantial support)

Differential Diagnosis

Specific language disorder. These children have a significant delay in language development and may have difficulty learning how to read. Impaired language development can also affect a child's social functioning. Children with isolated language delay do not have the spectrum of impairments characteristic of ASD.

Deafness. Though deaf children may have great difficulty learning to talk, they usually have normal or heightened use of non-verbal behaviors (gestures, mime, facial expressions) to communicate.

Selective mutism. Children with selective mutism speak and behave normally at home with their families but are functionally mute in other environments. Children with autism may also have selective mutism.

Reactive attachment disorder. Children who have experienced social/emotional neglect and maltreatment may develop some of the clinical features of ASD. When they are placed in a nurturing, stimulating environment and are well cared for, the "autistic" features spontaneously improve.

Fetal alcohol syndrome and ASD each has distinct diagnosis criteria though they can occur with overlapping characteristics. Children with FASD are usually more able than autistic children to use gestures and nonverbal communication to interact, demonstrate empathy, and express enjoyment in social overtures. ASD and FASDs differ in their characteristic patterns of cognitive disability. One study found that 79% of children with ASD had a higher nonverbal than verbal IQ; the opposite was true for children with FASDs. [Bishop: 2007] For more details, see Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FAQ).

Rett syndrome. Many children with Rett, but not all, may meet criteria for ASD and thus may have both. While stereotypic hand movements, impaired social skills, and lack of speech can occur in both autism and Rett syndrome, girls with Rett syndrome usually have decelerated head growth, hand wringing and lack of purposeful hand movements. They may develop breathing abnormalities or mobility impairments that are not characteristic of autism. Additionally, girls with Rett syndrome tend to prefer people to objects, whereas social connections may be more challenging for children with autism. See Rett Syndrome.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Many children with ASD meet criteria for OCD, particularly when they are older. Most children with OCD, however, do not meet criteria for ASD.

Landau-Kleffner syndrome (LKS). This syndrome, also called acquired epileptic dysphasia, is characterized by normal language development followed by loss of language. The loss of language in LKS typically occurs after 3 years of age and is associated with a relative sparing of social skills. This deterioration in language is associated with characteristic seizure activity in the temporal lobe of the brain. Children with isolated LKS do not meet criteria for ASD.

Schizophrenia. Like autism, schizophrenia is a developmental disorder in which impairments in social and emotional functioning, changes in language functioning, and stereotypies and other unusual behaviors may occur. The onset of schizophrenia is later than that of autism. Onset of schizophrenia is rare during childhood and usually occurs during late adolescence or adulthood. The hallmark clinical signs are hallucinations and delusions. Schizophrenia occurs in about 1% of the general population and rarely in older individuals with ASD. The lifetime prevalence of psychotic disorders/schizophrenia in adults with autism is about 10%. [Buck: 2014]

Schizoid, schizotypal, and avoidant personality disorder. Individuals with these disorders, in isolation, may have some of the social and emotional features seen in some individuals with ASD (social avoidance, social anxiety, lack of social interest). They do not typically meet diagnostic criteria for ASD.

Medical Conditions Causing Autism Spectrum Disorder

Angelman syndrome is associated with global developmental delay in early childhood with initial hypotonia, progressive spasticity, and seizures. These children are often non-verbal, and about 34% may display social and behavioral characteristics suggestive of ASD. See Angelman Syndrome.

CHARGE syndrome. ASD phenomenology has been found in 30% or more of affected individuals. [Richards: 2015]

Fragile X syndrome. In one large study, 50% of the males and nearly 20% of females met DSM-5 criteria for ASD. [Kaufmann: 2017] Features suggestive of fragile X include ID, macrocephaly, protuberant ears, hyperextensible joints, hypotonia, and post-pubertal macro-orchidism. See Fragile X Syndrome.

Neurofibromatosis is characterized by cafe-au-lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, ocular Lisch nodules, and neurofibromas. It has been estimated that NF1 prevalence among a population-based sample of 8-year-old children with ASD (1-in-558). [Bilder: 2016] See Neurofibromatosis Type 1.

Down syndrome. It is estimated that 6 to 16% of children with Down syndrome have features of or meet criteria for ASD. [Johnson: 2007] See Down Syndrome.

Tuberous sclerosis is a neurocutaneous disorder characterized by ash-leaf spots (hypopigmented macules), fibroangiomata, intellectual disability, renal and CNS hamartomas, and seizures. Greater than 50% of individuals with tuberous sclerosis will have features suggestive of autism, particularly if cortical tubers are present in the temporal lobe of the brain. Examination with a Wood's lamp may be necessary to detect cutaneous markers. See Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC).

Untreated phenylketonuria was historically associated with a significant number of cases of ASD and ID. With newborn screening and dietary intervention, this is now rarer. See PKU and Pterin Defects.

For other single gene disorders, including mutations in MECP2 and PTEN - see table 5 in [Schaefer: 2013].

Comorbid & Secondary Conditions

Sleep disturbances, especially insomnia, occur in up to 83% of children with autism regardless of cognitive ability. [Jeste: 2011] In the absence of an etiologic medical factor, such as obstructive sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, gastroesophageal reflux, and nocturnal seizures, management should focus on sleep hygiene, behaviors such as bedtime opposition, and limitation of daytime sleep. The Questionnaire to Help Identify Underlying Medical Conditions in Children with Autism (AAP) (

281 KB) includes 29 questions for parents to help identify medical contributors to sleep

issues in children with autism. [Malow: 2012]

281 KB) includes 29 questions for parents to help identify medical contributors to sleep

issues in children with autism. [Malow: 2012]

Gastrointestinal disorders. Children with ASD suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms, such as Constipation, diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, as often or more often than other children. The prevalence has been reported as high as 70% in some studies. [Buie: 2010]

Sensory integration/processing challenges. Children with ASD can present with abnormal sensory behaviors, such as appearing to be under- or over-stimulated by certain sensory conditions. A standardized measure called the Short Sensory Profile (

269 KB) can screen children ages 3-10

years for these problems. It is unclear whether children with sensory problems have

a defined disorder of brain pathways leading to these deficits, or if these problems

are merely symptoms associated with other behavioral or developmental disorders.

Despite the lack of a widely accepted framework for diagnosing sensory processing

disorder, many children with ASD seem to benefit from sensory-based therapies.

269 KB) can screen children ages 3-10

years for these problems. It is unclear whether children with sensory problems have

a defined disorder of brain pathways leading to these deficits, or if these problems

are merely symptoms associated with other behavioral or developmental disorders.

Despite the lack of a widely accepted framework for diagnosing sensory processing

disorder, many children with ASD seem to benefit from sensory-based therapies.Psychiatric comorbidity. Occurrence rates for various disorders, as identified by Lecavalier, include ADHD (81%), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (46%), conduct disorder (12%), any anxiety disorder (42%), and any mood disorder (8%). Two or more psychiatric disorders were identified in 66% of the sample. Of those who met criteria for ADHD, 50% also met criteria for ODD and 46% for any anxiety disorder. [Lecavalier: 2019]

History & Examination

As with all children, ongoing management should include monitoring growth parameters and developmental progress. The clinician should remain alert for the presence of medical, behavioral, and psychiatric comorbidities.

Current & Past Medical History

- A history of genetic disorders, seizures, encephalopathic events, and neurologic disorders

- Symptoms relating to disorders of attention, mood, anxiety, and attachment

- Sleep issues: A detailed sleep history includes asking about bedtime routine and sleep hygiene, sleep onset and duration, pattern of nighttime awakenings, frequency of snoring, and presence of restlessness.

- Diet: Children with ASD often experience aversion to certain oral textures, severely restricted food choices, and poor self-feeding skills requiring significant feeding support. Inquire about the use of dietary restriction to manage symptoms.

- Gastrointestinal disturbances: Discomfort due to abdominal pain or constipation may contribute to behavior problems and difficulties in toilet training.

- Use of medications, both prescription and supplements/complementary/alternative medications.

- Behavioral concerns in the home and in educational settings

- Frequency, duration, and type of developmental therapies utilized (speech, occupational, behavioral, Applied Behavioral Analysis [ABA])

Family History

Pregnancy/Perinatal History

Developmental & Educational Progress

- Language. Inquire about the use of verbal and non-verbal communication (e.g., sign language), the age of onset, and about any regression in their use. Ask about receptive language skills as well.

- Gross motor skills. Some children have delayed gross motor skills with poor motor planning and/or mild hypotonia, while others have typical or advanced gross motor skills.

- Fine motor/adaptive skills. Children with ASD may have difficulties in motor planning or limited ability to attend, impairing their ability to learn new skills. They may show advanced skills when it comes to preferred activities (favorite games/toys, computer keyboard use) but delays in age-appropriate tasks, such as drawing, dressing, or eating with utensils.

- Early Intervention. For the child less than 3 years of age, ask about involvement in an Early Intervention Part C Program, the type(s) of therapy being received (speech, occupational, behavioral, play therapy), their frequency and duration, and whether the developmental goals are being met.

- Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and 504 Plan. Although many children over the age of 3 should have an IEP in place, a 504 plan is sufficient for some children. For children with an IEP, ask if the child is meeting IEP goals and making appropriate developmental strides.

- Other therapy. Assess the potential benefit of private speech, occupational, and/or behavioral therapy services outside of the Early Intervention or school setting.

Social & Family Functioning

The heterogeneity and unpredictable course of children with ASD can contribute to parents’ frustration, especially when combined with long waiting lists for assessments. Families may also struggle with major life adjustments, such as a parent leaving their job to help coordinate interventions or needing to pay out of pocket for services not covered by other means. Managing problematic behaviors at home can also be difficult for families. [Martínez-Pedraza: 2009]

Many states have Medicaid waivers, autism assistance provisions, and mandates that require certain insurers to provide coverage for ASD-related services. Ask families if they need or have found state-mandated ASD benefits. Autism and Insurance Coverage | State Laws (NCSL) has state-by-state information.

Physical Exam

Appropriate screening tools, coupled with observation of the child in the office, can help identify children at risk who should be referred for further evaluation. In the exam room, watch how the child interacts and uses eye contact with the parents. Try to engage the child in a social game requiring reciprocity, like peek-a-boo, to see if they will engage in this activity or draw others’ attention to interesting things around them. [Zwaigenbaum: 2009] Also, call the child’s name to see if he or she looks. Young children with ASD are less likely to orient to name, and when they do, it is less often and slower than typically developing peers do. [Campbell: 2019] Malnutrition may also be present given the prevalence of restricted eating patterns, even in the setting of a higher risk for obesity. [Shmaya: 2015]

General

Growth Parameters

Measure growth parameters, including head circumference. Macrocephaly is common in children with autism. Atypical antipsychotics may cause excessive weight gain. Poor weight gain may be seen in children with an overly restrictive diet or those using stimulant medication.

Skin

HEENT/Oral

Note ear size, shape, and placement. Individuals with fragile X

syndrome may have large ears. Strabismus or nystagmus may be present in

individuals with fragile X and other genetic syndromes. Visual difficulties

may contribute to behavioral problems.

In a child

with acute worsening of behavior, examine for otitis media, sinusitis, and

pharyngitis. A non-verbal child may not be able to articulate discomfort

and, instead, may present with behavioral difficulties.

Individuals with bruxism, oral sensitivity, and/or

poor dental hygiene will be at risk for caries and require regular dental

care. Abnormalities of dentition or the palate may suggest a genetic

etiology.

Abdomen

Acute or chronic abdominal pain may cause a change in behavior in the child unable to verbalize discomfort. A palpable fecal mass may be present in children with chronic constipation. See Constipation for assessment details.

Extremities/Musculoskeletal

Examine for atypical or dysmorphic features. Evaluate for ankle flexion contractures related to chronic toe-walking, which is common in ASD and may lead to calf hypertrophy and, at times, limited ankle dorsiflexion.

Neurologic Exam

Children with ASD may have normal or decreased muscle tone. Hypertonicity and/or hyperreflexia should prompt evaluation for an underlying neurologic disorder. Calf hypertrophy must be distinguished from the pseudohypertrophy seen in muscular dystrophy, which may also involve language and other developmental delays. Changes in muscle tone or other focal findings may suggest an alternative or co-occurring diagnosis. Though repetitive/stereotypic behavior is the only motor problem among the diagnostic criteria for ASD, delays and deficits can be seen in multiple areas, including fine and gross motor skills, gait and coordination, motor planning, and postural control. When evaluating gait, observe for toe-walking, variable length of stride and timing, ataxia, incoordination, or problems with postural stability. [Jeste: 2011]

Testing

Sensory Testing

Laboratory Testing

- Serum lead screening, CBC, and iron studies may be indicated for children with a history of pica or global delay and those who mouth non-food items.

- Assess thyroid function (TSH and free T4) in those with global delay.

- Consider obtaining a CBC and serum ferritin in children with disordered/restless sleep.

- Consider creatine phosphokinase (CPK) in children with gross motor delay and hypotonia, particularly if weakness and/or calf pseudohypertrophy are evident.

- Consider metabolic screening with serum amino acids and

urine organic acids if any of the following are present:

- Profound ID

- Weakness or easily fatigued

- Cyclical vomiting or lethargy

- Failure to thrive or poor growth

- Motor regression or severe motor delay

- Unusual odor

- Consanguinity

- Note: Inborn errors of metabolism do not typically present with isolated autism in the absence of other signs and symptoms.

Imaging

- Many children on the autism spectrum have idiopathic macrocephaly. Neuroimaging should be performed only if there is concern for intracranial pathology (focal neurologic abnormality, neurocutaneous stigmata, rapid increase in head circumference).

- Estimated rates of true epilepsy in children with ASD are 5-38%. EEG evaluation is not recommended in the absence of clinical evidence of seizures because insignificant EEG abnormalities are often present. The risk of developing seizures increases in individuals with comorbid moderate-to-severe intellectual disability and in those with a genetic syndrome. [Minshew: 1997] [Volkmar: 1990] [Deykin: 1979]

- Indications for obtaining an EEG include history of language regression, tonic/clonic activity, and staring spells that the child cannot be distracted from. Seizures may also occur in sleep and should be considered if there are acute changes.

- There is a bi-modal distribution of the onset of seizure activity in ASD, with peaks in early childhood and adolescence. Consider new-onset seizure activity in the adolescent with acute behavior changes, particularly in those individuals with ID. [Johnson: 2007] [Jeste: 2011]

Genetic Testing

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Developmental - Behavioral Pediatrics (see RI providers [12])

Psychiatry/Medication Management (see RI providers [80])

General Counseling Services (see RI providers [30])

Occupational Therapy (see RI providers [21])

Speech - Language Pathologists (see RI providers [33])

116 KB) provides detail.

116 KB) provides detail.

Medical Genetics (see RI providers [4])

Sleep Disorders (see RI providers [2])

Pediatric Dentistry (see RI providers [54])

Developmental - Behavioral Pediatrics (see RI providers [12])

Treatment & Management

Overview

If possible, services for individuals with ASD should be provided in the context of a transdisciplinary team approach, which goes beyond a multidisciplinary team with the explicit inclusion of patients/caregivers in the decision-making process from beginning to end. Patients and caregivers join the medical team and contribute to any debate among medical team members as their assessment and plan are discussed. This team may also include developmental pediatrics, child psychiatry, genetics, genetic counseling, gastroenterology, neurology, speech-language pathology, case managers, behaviorists, psychologists, social workers, and selected therapies.

Pearls & Alerts for Treatment & Management

SleepSleep needs to be a central focus of care. Ask families about sleep and monitor carefully. For further management tips, see [Malow: 2012].

Have a low threshold for referral to behavioral interventionThe only evidence-based interventions for core autism features are behavioral interventions. This is particularly impactful when initiated at a very young age (early preschool period). If you have a young patient diagnosed with autism, strongly consider referring to behavioral intervention services.

AgitationAntipsychotics are often used to treat agitation, especially when placement is at risk. However, an exhaustive search for causes of agitation should be completed before considering the use of medications to target behavior.

Sensory integration/processing challengesIf a child’s therapist is using sensory-based therapies, help families assess progress with specific, measurable goals using behavior diaries or rating scales. [Zimmer: 2012] The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD includes a criterion regarding hyper-or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment in these children. [Weitlauf: 2017] Based on a recent systematic review, some interventions targeting sensory challenges in ASD may yield modest short-term improvements in sensory- and ASD severity outcomes. The AAP recommends not using sensory processing disorder as a diagnosis at this time. [Zimmer: 2012]

How should common problems be managed differently in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Growth or Weight Gain

Development (Cognitive, Motor, Language, Social-Emotional)

Over the Counter Medications

Prescription Medications

Common Complaints

Systems

Learning/Education/Schools

Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) uses psychology techniques to increase the frequency of desired behaviors and decrease the frequency of undesired or maladaptive behaviors. This model is the most studied of the therapy-based interventions. Teaching sessions are highly structured and behavioral data is methodically collected. When initiated early and conducted 30-40 hours per week, ABA-based interventions lead to sustained cognitive gains, improved communication, improved academic functioning, and better global outcomes. Several evidenced-based ABA-based methods include the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) and Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT).

Critics of ABA suggest that skills taught by this method do not generalize well to the natural environment and that such an intense program is prohibitively difficult and costly. Newer approaches using basic ABA methodology with more emphasis on teaching in the natural environment (Incidental Teaching, Pivotal Response Training or Natural Language Paradigm, and Milieu Teaching) are designed to address issues of generalizability and encourage the spontaneous use of communication. These integrate teaching opportunities in day-to-day activities (meals, baths, and playtimes). [Vismara: 2010] [Hyman: 2020]

Developmental or relationship-based models target the core deficits of autism developmental, individual-difference, relationship-based model (DIR), the relationship-development intervention (RDI), and social communication/emotional regulation/transactional support (SCERTS). A specific version of the DIR model, commonly referred to as Floortime, emphasizes emotional development, sensory processing, motor planning, relationships, and interactions using techniques that allow the child to lead interactions while challenging them towards greater mastery of social, emotional, and intellectual abilities. These interventions are often attractive to families because they are play-based and can be readily taught to family members. The empiric evidence supporting developmental strategies is limited.

The TEACCH Autism Program emphasizes organization of the physical environment, structured work and activity sessions, visual schedules, and visually structured activities. While it has not been as rigorously studied as ABA, TEACCH is supported by a growing body of empiric evidence effectiveness when implemented in addition to school and residential treatment programming. [Panerai: 2009]

The LEAP (Learning Experiences and Alternative Program for Preschoolers and their Parents) integrates children with ASD with typically developing peers in preschool early on. The child’s peers are taught to facilitate their social and communication skills, and families learn behavioral strategies for improved interactions. [Strain: 2011]

Various social skills interventions have been developed to address the core deficits faced by children with ASD. Carried out individually or in small groups, these may involve the use of social stories, video modeling, or playgroups in which adult facilitators prompt appropriate interactions between participants with positive reinforcement for appropriate spontaneous interactions. Social Stories (described further, below) has become a popular intervention to target social understanding and behaviors in children with ASD. A review article, [Bohlander: 2012], provides detailed information about the different approaches to social skills training.

The following may be useful in advising parents about behavioral interventions for their child with ASD:

- Encourage parents to use evidence-based models that are available in their community.

- Guide families to find providers that are highly trained and qualified.

- Help families keep positive but realistic expectations for their child’s outcomes. Encourage them to focus on skill-building improvement rather than total recovery.

- Collaborate as much as possible with behavioral experts. Parents may be helpful in assessing medication effectiveness, identifying environmental issues that could affect medical issues, and helping with compliance. [LeBlanc: 2012]

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) (see RI providers [27])

Social Skills Training (see RI providers [14])

Early Intervention for Children with Disabilities/Delays (see RI providers [13])

Mental Health/Behavior

Anxiety

An anxiety disorder should be considered in a child with aggression or irritability associated with changes in routine, transitions between activities, separation from a caregiver, or interruption of repetitive or obsessive behaviors. Also, consider anxiety in the child who demonstrates acute changes in behavior associated with discrete situations that may cause fear. Management of anxiety may include both behavioral and pharmacologic approaches, including psychoeducation, coordination of care, modified cognitive behavioral therapy, and medication. See Assessment and Treatment of Anxiety in Youth With Autism Spectrum Disorders [Vasa: 2016].

Behavioral strategies

Visual schedules can help reduce anxiety and undesired behaviors surrounding transitions and changes in routine. Photographs, simple drawings, or computer-generated pictures can be used; families and educators may also download picture cards (many for free or all for a fee) from Do2Learn. This site also contains a free section with extensive materials for safety issues and activities of daily living.

Social Stories describe situations with relevant social cues, perspectives, and common responses in a defined style and format. The format can help individuals understand situations that cause anxiety and respond with more appropriate behaviors. A recent review of multiple controlled trials of Social Stories interventions found significant benefit related to social interactions. [Karkhaneh: 2010]

Medications

Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) use is supported by several randomized, controlled trials in children without ASD that have shown improvements in irritability and depressive symptoms, tantrums, anxiety, aggression, difficulty with transitions, and some aspects of social interactions and language. SSRIs trials in children with ASD are limited. SSRIs may cause nausea, drowsiness, gastrointestinal disturbance, agitation, behavioral activation, suicidal ideation, sleep disturbance, or other symptoms. An exhaustive search for causes of agitation should be completed before considering the use of medications to target behavior.

Alpha-2 agonists may reduce symptoms of anxiety, hyperactivity, and irritability. They may be particularly helpful in patients who experience behavioral activation with SSRIs. Alpha-2 agonists onset is immediate, as opposed to SSRIs, which take 3-4 weeks before being able to see the beginning of effects. Possible side effects are dose dependent. They may include over-sedation and dry mouth, hypotension, constipation, irritability, and cardiac arrhythmia.

Benzodiazepines should not be used as a first-line agent in the chronic management of anxiety, long-acting benzodiazepines (such as clonazepam) may be beneficial in individuals who do not tolerate alpha-2 agonists or SSRIs. They may also be used on a PRN situational basis if appropriate.

Atypical antipsychotic medications - risperidone and aripiprazole have received US Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of the symptoms of irritability and aggression in children and adolescents age 5 and age 6 (respectively) and older with ASD. This class of medication should not be considered first-line for anxiety in patients with ASD. If a detailed symptom history reveals that irritable and aggressive behavior may be due to underlying anxiety, then an SSRI or alpha-2 agonist may be more appropriate. Antipsychotic medications may be useful; however, if a patient does not tolerate treatment with an SSRI or alpha-2 agonist. These medications may cause appetite increase and weight gain, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hyperprolactinemia, extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, QTc prolongation, seizures, anticholinergic symptoms, and sedation. Patients may experience akathisia ("inner restlessness") when doses are titrated up or down. When ready to discontinue, these medications should be tapered over months to avoid excessive akathisia. [Sharma: 2012] [McPheeters: 2011] [Owen: 2009]

Depression

When considering a diagnosis of depression, take a behavioral history to establish a baseline for the child's disruptive or maladaptive behavior. Compare the patient's current state to his or her baseline, with particular attention to crying spells, enjoyment of activities, interest in being around others, sleep patterns, appetite, and energy level. Note the intensity, frequency, and duration of related maladaptive behaviors. Establish behavioral goals based on the behavioral history.

Medications

SSRIs are commonly used for depression in individuals with ASD. Psychotropic Medication Options for Common Target Symptom (Table 11) in [Hyman: 2020] offers further general guidance.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Individuals with ASD may also experience symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity, which can impair their ability to acquire new skills and function in the home and school environments.

Medications

While stimulant medications, such as methylphenidate, are effective in some children with ASD and ADHD symptoms, the response rate is lower than in typically developing children with isolated ADHD and the potential for adverse effects is higher. Stimulant medication may also increase anxiety. Clinical practice pathways for evaluation and medication choice for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in autism spectrum disorders [Mahajan: 2012] offers further information.

Clinicians should prescribe only medications with which they are familiar, including knowledge of indications and contraindications, potential adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, dosing, and monitoring recommendations. Consultation with a child and adolescent psychiatrist should be considered if a clinician is unfamiliar or uncomfortable with the use of such medications. If regular psychiatric care is not available, consider co-management or phone consultation with a child psychiatrist experienced in the management of children with ASD.

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Psychiatry/Medication Management (see RI providers [80])

Autism Programs (see RI providers [4])

Sleep

Underlying Medical Conditions

Common medical problems in children with ASD that may contribute to sleep difficulties include: [Johnson: 2008]

- Nutritional issues may cause chronic health issues, such as constipation and restless leg syndrome.

- Constipation and abdominal pain related to constipation can affect sleep. See Constipation.

- Periodic limb movement disorder/restless leg syndrome may be associated with low-iron stores.

- Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, such as burning and pain, can affect sleep. See Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease).

- Asthma symptoms can make sleeping difficult. See Asthma.

- Epilepsy rates can be as high as 1/3 among patients with ASD and may disturb sleep cycles. [Francis: 2013] See Seizures/Epilepsy.

- Altered sensory perception is a hallmark of an ASD diagnosis, and children with ASD may have a higher level of anxiety or sensitivity with respect to their immediate environment. See Anxiety Disorders. Children with ASD may also have altered pain perception, but struggle to communicate this to caregivers.

- Obstructive sleep apnea may be a possible cause of insomnia, especially since hypotonia can be seen in patients with ASD.

Problems in children with ASD are often related to poor sleep hygiene. After excluding medical contributors, educational and behavioral interventions are first-line treatment. [Malow: 2012] See Behavioral Techniques to Improve Sleep.

Sleep Medications

If sleep problems do not resolve with behavioral management and treatment of underlying conditions, consider sleep medication and/or consultation with a sleep specialist. Multiple review articles have found melatonin supplementation to have a consistent effect on sleep onset and sleep latency; sleep duration may also be improved, though this does not appear to be consistently true across all studies. [Rossignol: 2011] Details about medications for sleep can be found at Sleep Medications.

A high-level overview of the key steps in managing sleep disorders in children with ASD can be found at Algorithm for Management of Sleep Problems in Children and Adolescents Who Have ASD (AAP) (

277 KB). [Malow: 2012]

277 KB). [Malow: 2012]

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Sleep Disorders (see RI providers [2])

Communication

With knowledge of the communication methods used by the child and the communication-related therapies being employed, the primary care clinician can help the family evaluate their effectiveness, guide decisions regarding available choices, and advocate for eligibility or insurance coverage of important services.

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Speech - Language Pathologists (see RI providers [33])

Complementary & Alternative Medicine

Well-tolerated treatments showing efficacy - Recommend use as a first-line treatment

- Melatonin is well-tolerated and has been shown to help improve sleep. Continue to encourage behavioral management and good sleep hygiene. [Rossignol: 2011] [Andersen: 2008]

- Multivitamins are safe at recommended doses; avoid giving over the recommended daily amount to avoid vitamin toxicity. Since children with ASD may have very strict, particular diets, supplementation with a multivitamin can help with possible nutritional deficiencies. If a child has a measured nutritional deficiency, following established guidelines for replacement therapy with the appropriate nutrient would be considered standard treatment.

Well-tolerated treatments with inconclusive/unknown efficacy - Support use if a family indicates desire to try, but encourage objective monitoring of the treatment.

- Vitamin C is safe at recommended doses and from the diet. Some feel it has a role in oxidative stress, but there are no high-quality studies examining the use of Vitamin C in ASD.

- A gluten/casein-free diet has poor evidence. The theory behind use of the diet is that some children with ASD are unable to break down the proteins in gluten and casein in their food, leading to formation of opioid proteins that act on the brain to cause some symptoms of autism. Counsel families using this diet about the importance of adequate calcium, protein, and vitamin D intake since bone loss has occurred. [Millward: 2008] [Hediger: 2008]

- Vitamin B6, magnesium is considered a safe treatment with inconclusive efficacy based on studies. A Cochrane review did not show significant evidence to support its use in children with autism. [Nye: 2005]

- Amino acids (carnosine) are thought to have antioxidant properties that are relatively safe, but efficacy was only shown in 1 controlled trial over 8 weeks. Adverse effects can include irritability and hyperactive symptoms. In a study of 31 children with ASD, 800mg of L-carnosine was given with improvement on receptive language scores. These results have not been repeated. [Chez: 2002]

- Essential fatty acids (omega 3 fatty acid) appear safe, but their efficacy is inconclusive. Omega-3 fatty acids are found in fish and fish oil supplements. A Cochrane review demonstrated the lack of quality studies to support its efficacy in this population. [James: 2011]

Well-tolerated treatment but no evidence of efficacy - Discourage use.

- Secretin is a peptide in the GI tract that is used to treat peptic ulcers and evaluate pancreatic function. It was felt from animal studies that secretin could act as a neurotransmitter. It has been studied in many RCTs and has shown no evidence for effectiveness. [Krishnaswami: 2011] [Williams: 2012]

Unsafe or unknown safety and inconclusive or no efficacy - Discourage use.

- Medical marijuana

- Chelation therapy is unsafe, has no demonstrated efficacy, and should be discouraged - deaths have been reported in children. Chelation therapy was created to treat lead poisoning but was marketed as a treatment for ASD by propagating that individuals with ASD have problems eliminating heavy metals from the body. Potential serious side effects with treatment include kidney and liver problems, neutropenia, neurologic problems, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has no evidence for efficacy, and there may be safety concerns. This therapy has been very effective for treatment of decompression sickness, carbon monoxide poisoning, and wound infections. Treatments can cost thousands of dollars, are time-consuming, and can be associated with exacerbation of seizures and pulmonary issues. Immune therapies are unsafe and efficacy has not been demonstrated. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusion therapy can have severe side effects, including systemic reactions to the infusion.

- Antifungal agents are unsafe treatments and efficacy has not been demonstrated in studies to treat behavioral issues or core symptoms of autism.

- Medical marijuana use for people with autism is legal in several states. There is limited research, and no evidence, on the potential short-term, long-term, or neurodevelopmental risks and benefits of medical marijuana or its related compounds in ASD. The FDA for any medical purpose. See Statement on Medical Marijuana Use and Autism (Autism Science Foundation).

Nutrition/Growth/Bone

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Dieticians and Nutritionists (see RI providers [3])

Occupational Therapy (see RI providers [21])

Neurology

Gastro-Intestinal & Bowel Function

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Dieticians and Nutritionists (see RI providers [3])

Pediatric Gastroenterology (see RI providers [18])

Ask the Specialist

Should a child have a formal diagnosis of autism before he or she is referred for Early Intervention?

Diagnosis is not required for referral and cognitive, social, language, and adaptive outcomes are better for individuals with ASD when intervention is initiated early. This is likely true for other neurodevelopmental conditions that might raise concerns for parents or clinicians or result in a positive screening test. In some areas, limited access to developmental specialists may result in a delay of several months between referral and formal diagnosis. In some areas, limited access to developmental specialists may result in a delay of several months between referral and formal diagnosis. When a child is referred for a diagnostic evaluation, simultaneous referrals should be made to Early Intervention Part C Program and speech and occupational therapy, as deemed appropriate, to address the particular challenges of the child.

What are the roles of risperidone and aripiprazole in the management of autism?

No medication is known to treat the core symptoms of ASD. Risperidone and aripiprazole have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat the symptoms of aggression and irritability in children with ASD over 5 years of age. Before using it for this purpose, however, clinicians must consider the underlying function of the problem behavior. This may be secondary to pain, poor communication skills, problems with attention, a mood disorder, and/or anxiety disorders. Once determined, the cause of the behavior may be treated appropriately. Only when this is unsuccessful is it appropriate to target the symptom rather than the cause.

A patient would like to retain his diagnosis of Asperger syndrome, what advice should I give him?

Although some may wish to self-identify as having Asperger syndrome, it would be considered best practice to use the current classification as outlined in the DSM-5.

Should a child who has received a diagnosis of PDD-NOS be re-evaluated for social communication disorder?

If a child had received a diagnosis of PDD NOS (or Asperger syndrome or autistic disorder), DSM-5 indicates that they automatically qualify for the autism spectrum disorder diagnosis.

Resources for Clinicians

On the Web

Association for Science in Autism Treatment (ASAT)

A nonprofit organization that provides information, lists of conferences, suggested readings, and articles about evidence-based

autism treatments for clinicians and parents.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (OMIM)

Information about clinical features, diagnosis, management, and molecular and population genetics; Online Mendelian Inheritance

in Man, authored and edited at the McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

ADNP-Related Intellectual Disability and Autism Spectrum Disorder (GeneReviews)

Detailed information addressing clinical characteristics, diagnosis/testing, management, genetic counseling, and molecular

pathogenesis; from the University of Washington and the National Library of Medicine.

Interdisciplinary Technical Assistance Center on Autism and Developmental Disabilities

Clinical information, funding opportunities, training events, and other resources to help improve care for children with autism

and other developmental disabilities.

National Autism Center (NAC)

Information for professionals and families about the treatment of autism, including the National Standards Project, which

addresses evidence-based practice standards.

Pedialink Course: Identifying & Caring for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (AAP)

Free, self-paced online course reflecting the guidelines published in January 2020; sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Autism Initiatives (AAP)

Autism tools, practice guidelines, CME for pediatricians, and resources to share with families; American Academy of Pediatrics.

Helpful Articles

PubMed search for autism and children or adolescents, last 1 year

Lecavalier L, McCracken CE, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, McCracken JT, Tierney E, Smith T, Johnson C, King B, Handen B, Swiezy NB,

Eugene Arnold L, Bearss K, Vitiello B, Scahill L.

An exploration of concomitant psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorder.

Compr Psychiatry.

2019;88:57-64.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Buck TR, Viskochil J, Farley M, Coon H, McMahon WM, Morgan J, Bilder DA.

Psychiatric comorbidity and medication use in adults with autism spectrum disorder.

J Autism Dev Disord.

2014;44(12):3063-71.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Nath D.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the School-Age Child With Autism.

J Pediatr Health Care.

2017;31(3):393-397.

PubMed abstract

Volkmar F, Siegel M, Woodbury-Smith M, King B, McCracken J, State M.

Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2014;53(2):237-57.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

McCormick C, Hepburn S, Young GS, Rogers SJ.

Sensory symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder, other developmental disorders and typical development: A longitudinal

study.

Autism.

2016;20(5):572-9.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Clinical Tools

Assessment Tools/Scales

Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) ( 38 KB)

38 KB)

The AIMS test is a free, 12-item, anchored scale used to detect tardive dyskinesia and follow the severity in patients receiving

neuroleptic medications. It is administered by a clinician and takes about 5 minutes to complete. Scoring instructions included.

Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers – Revised, with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F)

A free, 2-step tool that screens for autism. Released in 2013 and replaces the previously used M-CHAT. Site provides screening

questions, a scoring template (an overlay), a scoring matrix compatible with Excel, and multiple language translations.

Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile (CSBS DP) Infant-Toddler Checklist ( 51 KB)

51 KB)

A free checklist with 24 questions and scoring sheet; Brookes Publishing Company.

Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) (WPS)

Designed for individuals >4 years old when ASD is suspected. Contains 40 yes/no questions, takes about 10 minutes to complete;

Western Psychological Services. Available for a fee.

Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ-3)

Parent-completed, age-specific questionnaires that screen for developmental delays in children between 1 month and 5½ years

old; available for purchase.

Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Social-Emotional (ASQ:SE-2)

A parent-completed series of 19 age-specific questionnaires screening communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem-solving,

and personal adaptive skills. Results are in a pass/fail format for domains; available for purchase.

Care Processes & Protocols

Algorithm for Management of Sleep Problems in Children and Adolescents Who Have ASD (AAP) ( 277 KB)

277 KB)

A Practice Pathway from A Practice Pathway for the Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Insomnia in Children and

Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders by Malow BA, Byars K, Johnson K, et al., published in Pediatrics (2012).

Toolkits

Autism Resource Toolkit (AAP)

Includes a comprehensive guide to the diagnosis and management of autism spectrum disorders, screening tools, patient handouts,

and more; from the American Academy of Pediatrics store on-line.

Other

Do2Learn

Families and educators may download or create picture cards (some for free or all for a fee) for schedule use, communication,

and the classroom.

Proloquo2go

Symbol-supported communication app for beginning to advanced communicators. Designed to promote growth of communication skills

and foster language development through research-based vocabularies; available for a fee.

Patient Education & Instructions

Translated Autism Resources (VFN)

Autism Fact Sheet and Learn the Signs: Act Early Autism Fact Sheet, each translated into Arabic, Bosnian, Burmese, English,

French,Nepali, Somali, Spanish, Swahili, and Vietnamese; Vermont Family Network.

100 Day Kit for Newly Diagnosed Families of Young Children (Autism Speaks)

Helps families of children ages 4 years and younger make the best possible use of the 100 days following the diagnosis. Several

forms are available to assist in the organization of medical records and tracking the effectiveness of treatments.

Melatonin and Sleep Problems in Autism: A Guide for Parents (Autism Speaks) ( 2.2 MB)

2.2 MB)

Discusses types of melatonin and the pros and cons of using them to help with sleep disorders in children with autism.

Autism Spectrum Disorder: What Every Parent Needs to Know, 2nd Edition (AAP)

Reliable information about how ASD is defined and diagnosed and the most current behavioral, developmental, educational, and

medical therapies. Topics covered align with the DSM-5 updates. Paperback and eBook versions available for purchase; American

Academy of Pediatrics.

Resources for Patients & Families

Information on the Web

Autism Spectrum Disorder (CDC)

Focused information about early warning signs, safety of vaccines, and autism; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Autism (healthychildren.org)

Answers to questions such as: How is autism diagnosed? If autism is suspected, what next? What are early signs? How do I keep

a child with autism from wandering?

Autism Speaks

A national organization dedicated to promoting autism-related research and education. Provides in-depth information about

fundraising for research and parent information about autism.

Different Roads to Learning

On-line catalogs specializing in learning materials and playthings for children with developmental disabilities, including

autism. Focus is on ABA resources.

Future Horizons

Commercial site offering information, training, and resources for families, teachers, and professionals for dealing with autism.

Sesame Street and Autism

An initiative to help people better understand autism and offer families ways to overcome common challenges and simplify everyday

activities using helpful videos, stories, and printable daily routine cards for social experiences.

National & Local Support

Autism Parent Focus Group ( 22 KB)

22 KB)

Read what parents of children with autism have to say about getting a diagnosis, the impact on siblings, where parents get

information, and the financial impact on families. The transcript is from a focus group in July 2009 in Utah.

Center for Parent Information and Resources (DOE)

Parent Centers in every state provide training to parents of children with disabilities and provide information about special

education, transition to adulthood, health care, support groups, local conferences, and other federal, state, and local services.

See the "Find Your Parent Center Link" to find the parent center in your state.

Studies/Registries

Studies Related to Autism (clinicaltrials.gov)

Studies looking at better understanding, diagnosing, and treating this condition; from the National Library of Medicine.

SPARK National Autism Study

Studies genetic, behavioral, and medical information from hundreds of thousands of people to advance research and discovery

in autism. Information is gathered online and participants mail in a saliva sample for genetic testing. The results are provided

to the participant. Funded and led by the Simons Foundation.

Services for Patients & Families in Rhode Island (RI)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | RI | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NM | NV | UT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Education/Schools | 9 | 7 | 8 | |||||

| Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) | 27 | 2 | 17 | 11 | 62 | |||

| Audiology | 24 | 3 | 22 | 8 | 22 | |||

| Autism Programs | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 56 | |||

| Developmental - Behavioral Pediatrics | 12 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9 | |||

| Dieticians and Nutritionists | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 | |||

| Early Intervention for Children with Disabilities/Delays | 13 | 3 | 34 | 30 | 51 | |||

| General Counseling Services | 30 | 1 | 10 | 209 | 298 | |||

| Medical Genetics | 4 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | |||

| Occupational Therapy | 21 | 1 | 17 | 22 | 37 | |||

| Pediatric Dentistry | 54 | 2 | 6 | 28 | 50 | |||

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 18 | 2 | 5 | 2 | ||||

| Pediatric Neurology | 18 | 5 | 5 | 8 | ||||

| Psychiatry/Medication Management | 80 | 3 | 37 | 53 | ||||

| Safety & Preparedness Education | 3 | 1 | 1 | 19 | 37 | |||

| Sleep Disorders | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Social Skills Training | 14 | 1 | 8 | 9 | 44 | |||

| Speech - Language Pathologists | 33 | 4 | 23 | 11 | 65 | |||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Authors & Reviewers

| Authors: | Quang-Tuyen Nguyen, MD |

| Mariah Mthembu, MD | |

| Senior Author: | Deborah Bilder, MD |

| Reviewer: | Paul Carbone, MD |

| 2016: update: Quang-Tuyen Nguyen, MDA |

| 2015: update: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPA; Sean Cunningham, Ph.D.CA |

| 2013: first version: Tara Buck, MDA; Deborah Bilder, MDSA; Paul Carbone, MDR; Lynne M. Kerr, MD, PhDA; G. Bradley Schaefer, MDCA |

Bibliography

Akins RS, Angkustsiri K, Hansen RL.

Complementary and alternative medicine in autism: an evidence-based approach to negotiating safe and efficacious interventions

with families.

Neurotherapeutics.

2010;7(3):307-19.

PubMed abstract

This review focuses on helping clinicians identify resources and develop strategies they may use to effectively negotiate

safe and effective use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments with families of children with autism spectrum

disorders (ASD), as well as other neurodevelopmental disorders.

American Psychiatric Association: DSM-5 Task Force.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Fifth ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing;

2013.

http://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425...

Anagnostou E, Hansen R.

Medical treatment overview: traditional and novel psycho-pharmacological and complementary and alternative medications.

Curr Opin Pediatr..

2011;23(6):621-7.

PubMed abstract

Accumulating data suggest a series of existing medications may be useful in ASD and large randomized clinical trials are necessary

to evaluate safety and efficacy of pharmaceuticals and alternative treatments.

Andersen IM, Kaczmarska J, McGrew SG, Malow BA.

Melatonin for insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders.

J Child Neurol.

2008;23(5):482-5.

PubMed abstract

Anderson DK, Liang JW, Lord C.

Predicting young adult outcome among more and less cognitively able individuals with autism spectrum disorders.

J Child Psychol Psychiatry.

2014;55(5):485-94.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Bilder DA, Bakian AV, Stevenson DA, Carbone PS, Cunniff C, Goodman AB, McMahon WM, Fisher NP, Viskochil D.

Brief Report: The Prevalence of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Identified by the Autism

and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network.

J Autism Dev Disord.

2016;46(10):3369-76.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Bishop S, Gahagan S, Lord C.

Re-examining the core features of autism: a comparison of autism spectrum disorder and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

J Child Psychol Psychiatry.

2007;48(11):1111-21.

PubMed abstract

Bohlander AJ, Orlich F, Varley CK.

Social skills training for children with autism.

Pediatr Clin North Am.

2012;59(1):165-74, xii.

PubMed abstract

This article summarizes the current literature on social skills training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum

disorders. The article describes several different methods of social skills training, along with a summary of research findings

on effectiveness.

Buck TR, Viskochil J, Farley M, Coon H, McMahon WM, Morgan J, Bilder DA.

Psychiatric comorbidity and medication use in adults with autism spectrum disorder.

J Autism Dev Disord.

2014;44(12):3063-71.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Buie T, Campbell DB, Fuchs GJ 3rd, Furuta GT, Levy J, Vandewater J, Whitaker AH, Atkins D, Bauman ML, Beaudet AL, Carr EG,

Gershon MD, Hyman SL, Jirapinyo P, Jyonouchi H, Kooros K, Kushak R, Levitt P, Levy SE, Lewis JD, Murray KF, Natowicz MR, Sabra

A, Wershil BK, Weston SC, Zeltzer L, Winter H.

Evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders in individuals with ASDs: a consensus report.

Pediatrics.

2010;125 Suppl 1:S1-18.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

A multidisciplinary panel reviewed the medical literature with the aim of generating evidence-based recommendations for diagnostic

evaluation and management of gastrointestinal problems in individuals with ASDs.

Campbell K, Carpenter KL, Hashemi J, Espinosa S, Marsan S, Borg JS, Chang Z, Qiu Q, Vermeer S, Adler E, Tepper M, Egger HL,

Baker JP, Sapiro G, Dawson G.

Computer vision analysis captures atypical attention in toddlers with autism.

Autism.

2019;23(3):619-628.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Carbone PS, Campbell K, Wilkes J, Stoddard GJ, Huynh K, Young PC, Gabrielsen TP.

Primary Care Autism Screening and Later Autism Diagnosis.

Pediatrics.

2020;146(2).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Autism spectrum disorder.

(CDC); (2019)

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/index.html. Accessed on August 2020.

Chez MG, Buchanan CP, Aimonovitch MC, Becker M, Schaefer K, Black C, Komen J.

Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of L-carnosine supplementation in children with autistic spectrum disorders.

J Child Neurol.

2002;17(11):833-7.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

L-Carnosine, a dipeptide, can enhance frontal lobe function or be neuroprotective. It can also correlate with gamma-aminobutyric

acid (GABA)-homocarnosine interaction, with possible anticonvulsive effects. Although the mechanism of action of L-carnosine

is not well understood, it may enhance neurologic function, perhaps in the enterorhinal or temporal cortex.

Dawson G.

Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder.

Development and Psychopathology.

2008;20(3):775-803.

PubMed abstract

Advances in several related fields have contributed to a more optimistic outcome for individuals with autism spectrum disorder

(ASD). For the first time, prevention of ASD is plausible. This article describes a developmental model of risk, risk processes,

symptom emergence, and adaptation in ASD that offers a framework for understanding early brain plasticity in ASD and its role

in prevention of the disorder.

Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, Greenson J, Donaldson A, Varley J.

Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model.

Pediatrics.

2010;125(1):e17-23.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Deykin EY, MacMahon B.

The incidence of seizures among children with autistic symptoms.

Am J Psychiatry.

1979;136(10):1310-2.

PubMed abstract

Duchan E, Patel ER.

Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders.

The Pediatric Clinics of North America.

2012;59(1):27-43.

PubMed abstract

Epidemiologic data gathered over the last 40 years report that the conservative estimate of autistic spectrum disorder prevalence

is 27.5 per 10,000 individuals; however, the prevalence estimate based on newer surveys is 60 per 10,000 individuals. This

article reviews the incidence, prevalence, and risk factors for autism.

Erland LA, Saxena PK.

Melatonin Natural Health Products and Supplements: Presence of Serotonin and Significant Variability of Melatonin Content.

J Clin Sleep Med.

2017;13(2):275-281.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Farley MA, McMahon WM, Fombonne E, Jenson WR, Miller J, Gardner M, Block H, Pingree CB, Ritvo ER, Ritvo RA, Coon H.

Twenty-year outcome for individuals with autism and average or near-average cognitive abilities.

Autism Res.

2009;2(2):109-18.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Previous studies found substantial variability in adult outcome for people with autism whose cognitive functioning was within

the near-average and average ranges This study examined adult outcome for 41 such individuals. Cognitive gain was associated

with better outcome, as was better adaptive functioning. While all participants had baseline IQs in the nonimpaired range,

there was limited evidence to support the use of other early childhood variables to predict adult outcome.

Francis A, Msall M, Obringer E, Kelley K.

Children with autism spectrum disorder and epilepsy.

Pediatr Ann.

2013;42(12):255-60.

PubMed abstract

Furuta GT, Williams K, Kooros K, Kaul A, Panzer R, Coury DL, Fuchs G.

Management of constipation in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders.

Pediatrics.

2012;130 Suppl 2:S98-105.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Gabrielsen TP, Farley M, Speer L, Villalobos M, Baker CN, Miller J.

Identifying autism in a brief observation.

Pediatrics.

2015;135(2):e330-8.

PubMed abstract

Study examining the reliability of short clinical observations for atypical behaviors to detect autism risk. Expert raters

missed 39% of cases in the autism group as needing autism referrals based on brief but highly focused observations.

Goodwin A, Matthews NL, Smith CJ.

The Effects of Early Language on Age at Diagnosis and Functioning at School Age in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

J Autism Dev Disord.

2017;47(7):2176-2188.

PubMed abstract

Grønborg TK, Schendel DE, Parner ET.

Recurrence of autism spectrum disorders in full- and half-siblings and trends over time: a population-based cohort study.

JAMA Pediatr.

2013;167(10):947-53.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Hediger ML, England LJ, Molloy CA, Yu KF, Manning-Courtney P, Mills JL.

Reduced bone cortical thickness in boys with autism or autism spectrum disorder.

J Autism Dev Disord.

2008;38(5):848-56.

PubMed abstract

Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM.

Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Pediatrics.

2020;145(1).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Comprehensive clinical report addressing the prevalence, clinical symptoms, screening and diagnosis, etiologic evaluation,

and interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder.

James S, Montgomery P, Williams K.

Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation for autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2011(11):CD007992.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Reviewed the efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids for improving core features of ASD and associated symptoms. To date there is

no high quality evidence that omega-3 fatty acids supplementation is effective for improving core and associated symptoms

of ASD.

Jeste SS.

The neurology of autism spectrum disorders.

Curr Opin Neurol.

2011;24(2):132-9.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Neurological comorbidities in autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are not only common, but they are also associated with more

clinical severity. This review highlights the most recent literature on three of autism’s most prevalent neurological comorbidities:

motor impairment, sleep disorders, and epilepsy.

Johnson CP, Myers SM.

Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders.

Pediatrics.

2007;120(5):1183-215.

PubMed abstract

Comprehensive clinical report addressing the definition, history, epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, early signs, neuropathologic

aspects, and etiologic possibilities in autism spectrum disorders. This report also provides the primary care provider with

an algorithm for assistance in the early identification of children with autism spectrum disorder.

Johnson KP, Malow BA.

Sleep in children with autism spectrum disorders.

Curr Treat Options Neurol.

2008;10(5):350-9.

PubMed abstract

Karkhaneh M, Clark B, Ospina MB, Seida JC, Smith V, Hartling L.

Social Stories ™ to improve social skills in children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review.

Autism.

2010;14(6):641-62.

PubMed abstract

Since the early 1990s, Social Stories™ have been suggested to positively affect the social development of children with autism

spectrum disorder (ASD). This review underscores the need for further rigorous research and highlights some outstanding questions

regarding maintenance and generalization of the benefits of Social Stories ™.

Kaufmann WE, Kidd SA, Andrews HF, Budimirovic DB, Esler A, Haas-Givler B, Stackhouse T, Riley C, Peacock G, Sherman SL, Brown

WT, Berry-Kravis E.

Autism Spectrum Disorder in Fragile X Syndrome: Cooccurring Conditions and Current Treatment.

Pediatrics.

2017;139(Suppl 3):S194-S206.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Krishnaswami S, McPheeters ML, Veenstra-Vanderweele J.

A systematic review of secretin for children with autism spectrum disorders.

Pediatrics.

2011;127(5):e1322-5.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Secretin has been studied extensively in multiple randomized controlled trials, and there is clear evidence that it lacks

benefit. The studies of secretin included in this review uniformly point to a lack of significant impact of secretin in the

treatment of ASD symptoms.

LeBlanc LA, Gillis JM.

Behavioral interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders.

Pediatr Clin North Am.

2012;59(1):147-64, xi-xii.

PubMed abstract

This article describes the core features of behavioral treatments, summarizes the evidence base for effectiveness, and provides

recommendations to facilitate family understanding of these interventions and identification of qualified providers. Recommendations

are also provided for collaboration between pediatric providers and behavior analysts who are serving families of individuals

with ASDs.

Lecavalier L, McCracken CE, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, McCracken JT, Tierney E, Smith T, Johnson C, King B, Handen B, Swiezy NB,

Eugene Arnold L, Bearss K, Vitiello B, Scahill L.

An exploration of concomitant psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorder.

Compr Psychiatry.

2019;88:57-64.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Leyfer OT, Folstein SE, Bacalman S, Davis NO, Dinh E, Morgan J, Tager-Flusberg H, Lainhart JE.

Comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with autism: interview development and rates of disorders.

J Autism Dev Disord.

2006;36(7):849-61.

PubMed abstract

Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore PS, Shulman C, Thurm A, Pickles A.

Autism from 2 to 9 years of age.

Arch Gen Psychiatry.

2006;63(6):694-701.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

The objective of this study is to examine the stability of autism spectrum diagnoses made at ages 2 through 9 years and identify

features that predicted later diagnosis. Diagnostic stability at age 9 years was very high for autism at age 2 years and

less strong for pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. Judgment of experienced clinicians, trained on standard

instruments, consistently added to information available from parent interview and standardized observation.

Maenner MJ, Rice CE, Arneson CL, Cunniff C, Schieve LA, Carpenter LA, Van Naarden Braun K, Kirby RS, Bakian AV, Durkin MS.

Potential impact of DSM-5 criteria on autism spectrum disorder prevalence estimates.